Dad gets Attaboy but goes one comment too far

Have you ever been on the job and something went well? Come on, it could happen …

No, I mean, where you did something so right that you wish someone would turn around, see what you just did, and cry out, “Hey, nice job! That was really great!”

Or you did something so good you wish you could just tell everyone yourself? Kind of like, “Hey, did you see that!”

Well, you should get yourself a column! Because I’m about to tell you something I think I did really well.

But then … something I did not so well at too.

They were both on the job of being a dad. In the same conversation. With the same kid.

Stay with me on this …

Being a dad, being a parent, is a job. Yeah, I know, I’’s not construction work. It’s not boxing. It’s not being a high school principal.

(Photo via Wikipedia)

But if you have any pride in the way you’re doing it, it’s hard work. Like construction, it’s mental and manual labor. Like a boxer, you definitely take some punches.

And like a principal, there are some lessons you just can’t seem to get through to that one kid you take a little extra time with. And it can be very frustrating.

Let me tell you what happened. Here’s the scene:

I was having a conversation with my son, a high school junior, about his grades, his effort and his plans for after high school.

Or rather, his below average grades, his limited effort, and his complete lack of plans for after high school.

He wants to be a filmmaker. He has himself convinced he doesn’t need college for that.

Damn you and your pulp fiction, Quentin Tarantino!

My son has spent the last couple of years working on short films — really short. And learning about lighting and how to run a camera. And you know what? He has a little talent for all of it.

Meanwhile, he has spent very little time learning English, or Math, or History. Enough to get by. BARELY enough. But, then what?

He expressed interest in film school for a while, rather than a traditional college. But feels like he can transition to the profession maybe even without film school. Or without even having a job as a high school kid to save some money.

Shut your eyes, Stanley Kubrick!

He is now convinced that it can be done.

That somehow, a kid with average grades, no college, and parents who cannot finance his first few efforts is suddenly going to wind up a red carpet phenom, the newest Hollywood Director to take the world by storm.

(Photo via Wikipedia)

Sink that ship, James Cameron!

Yes, my son’s idea comes from the fact that, on this topic, he has done a little research. If you Google “directors who never went to film school” or “ …never went to college,” you will come up with a list of ten or so popular, successful and in some cases very well known directors.

It’s impressive. And subversive. And annoying.

Look, I’m a writer. An artist. I get it. I was a professional stand-up comic for 12 years. I get the Bohemian thing. I really do.

But I went to college first. I had a real job waiting for me when I came out, because I hustled, and I kicked butt as an intern. When after a few years I decided to leave that good job and go into entertainment, I had a back up plan if it didn’t work.

He doesn’t have a back-up plan. He doesn’t have a plan, period.

He just feels like … it’s going to happen. He is trying to convince me that he himself is convinced.

In his mind, it’s not going to be difficult for an average high school student — hopefully a high school graduate — with no money or plan, to get an apartment, get money and make movies.

He refuses to listen to logic. His theory is that if they have done it, he can do it.

- He has his father’s stubborn Irish confidence. It’s genetics.

And so the other night, while discussing this once again, I was frustrated. And worn out. And felt like I was taking too many punches. Jabs — because as a teenager, his answers are one and two-word answers. There’s rarely enough response to be considered a body blow, or a knockout punch. Those short, dismissive, “whatever” answers are jabs, but they add up.

And so, even though he was wrong, I’m sure the judges at ringside would have had him ahead on points. Because his jabs stung a little, while my roundhouse factual swings were missing wildly, not landing, not sticking.

(Photo via Wikipedia)

Until … I hit the home run, I pulled something to say out of my back pocket that I’d never said or thought before. And I delivered it with so much passion and fervor and conviction that it surprised me. And I think it landed and stunned him.

When he once again led with, “But they didn’t go to college and you know who they are,” I countered with the following:

“Yeah, I know who they are. I also know about the guy who won the lottery twice and the one-handed guy that made it to the major leagues and the guy who got hit by lightning three times and lived. Do you know why I know about them?”

Of course he said nothing.

“Because those kinds of things are so freaking RARE that they get written about! Those are one in a million, or one in 10 million kinds of things! So of course they get written about! Like a director who never went to college!”

Silence. I pressed on.

“Do you know who doesn’t get their own story? The hundreds and thousands and millions of kids who come out of high school without a plan, with average grades, who either don’t go to college or can’t get into college. Because who wants to read a story about people who didn’t have a plan? Who wants to read about guys that are 30 and 40 and 50 working for minimum wage, or who are in jail because they had no options but to start stealing their food?”

Then I stopped. The silence told a lot. I had connected. I knew it. I knew it was good. I think I had just won a round, maybe the whole battle. I thought I might have just done some good. I was pleased with myself.

Immediately I thought of three or four parent friends of mine that I wanted to tell about this exchange, because it made sense. And it seemed to work.

I wish you could have been there to see it. But I hope you would have been gone by what happened next.

Clearly I had him rocked, on the ropes, just hoping to survive the round. I offered what I thought was a soft poke: “Why can’t you believe that I know a little bit about what I’m talking about?” I volleyed out.

He was hurt, swinging wildly, a teenage boy just looking to survive. “Because you’re an a**hole,” he flailed at me.

He was hurt. I knew he was saying anything. But instead of backing off, I jabbed back. I stared at him and said, “Apparently, it’s genetic.”

It barely glanced him. I think I winced more than he did. The judges immediately deducted two points for a low blow.

It was one of those, “I didn’t really mean to hit him low, but I did swing” kind of things. Clearly I gave back some of what I had won.

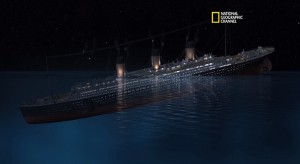

(Photo via YouTube video of National Geographic documentary on the Titanic)

The best I could hope for here now was a split decision. We talked a little more. Some of it still seemed to register. He agreed he could try harder at school and then went to bed.

I felt bad for the low blow, but still felt like the major points may have stuck.

The next day was a truce. Quick check on homework — talking about today, not next year or the next five years.

The next day? He had a 4-page permission slip for me to read and sign. For a school field trip to a college fair, where numerous schools were going to be presenting their information.

I’d like to think he wants more than just a bus ride.

Mike Brennan has been a Pulitzer Prize-nominated newspaper reporter, a magazine writer, a nationally touring stand-up comedian, a morning radio host, a professional auctioneer for numerous charities and a film and TV script consultant. He is currently working on a romantic comedy screenplay, and a humorous book on being a father, called The Tooth Fairy Doesn’t Pay for Yellow Teeth. He has lived in the Valley for 17 years, and has two teenage sons.