Columbia: How the ‘garden for growing people’ got planted and grew

This is the first of a series of 12 monthly essays over the next year leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration next June. It ran first in The Business Monthly, with a circulation of 25,000 in Howard and Anne Arundel counties, and after that will be published here on MarylandReporter.com and by our partner website, Baltimore Post-Examiner. The copyright is maintained by the author and may not be republished in any form without his express written consent. © 2016 Len Lazarick

By Len Lazarick

When I tell people I’ve lived in Columbia 43 years, some say, “Oh you must be a pioneer.” But a pioneer, in old-Columbia speak, is technically someone who moved here in its first year, 1967–68. A few of those 2,200 souls are left, and all can tell you of the first store, the first school, the first this and the first that.

But this monthly series of essays leading to Columbia’s 50th birthday next June is not meant as a piece of nostalgia. Many books and hundreds of articles have focused on the first decades of Columbia, the land acquisition, the planning. These essays are about Columbia as a lived experience that brings us to the present, with a long view of how we got here and how it evolved from the plan, and in many cases was not planned at all.

This is called a “memoir” because it is neither complete nor unbiased. It is Len Lazarick’s interpretation of Columbia’s 50 years, or at least some aspects of it, fact-based as much as possible.

For most of those years I was working as a journalist here, reporting and editing for the once-great Columbia Flier, and then The Business Monthly. I covered politics, state government, business and the school board.

I love Columbia, but of course, as a critical journalist, it is a love fully conscious of the town’s flaws and quirks; I am more critical than its most ardent fans.

As its visionary developer Jim Rouse intended, Columbia has truly been for me and many others “a garden for growing people.” I arrived at age 25 and truly grew up here; I made my living here; my wife and I bought three houses, thrived here, experienced disappointments and unemployment here; we had our daughters at its new hospital and now our grandsons were born here; we worship here, shop here, play here; I made mistakes here, had successes here, made many friends and a few enemies.

Columbia is not a perfect place or even necessarily the only ideal place to grow up and raise a family. But it was for us.

The Next America

Jim Rouse and the company that bore his name nicknamed this new town “The Next America,” a name that adorned the Exhibit Center in downtown before there really was a town.

In 1977, as Columbia celebrated its 10th birthday, I penned the lead essay in the Flier’s glossy commemorative magazine, “The People of Columbia,” full of pictures and profiles of the people who lived here.

My essay was titled “No Promised Land, No Next America: In the failure of great expectations, great promise still.” I thought, and still think, it was a balanced piece, an antidote to the hype and promotion that sometimes afflicted the early marketing. Jim Rouse didn’t agree.

“We didn’t know you felt that way,” he said to me shortly after the magazine came out. And, I was told, Howard Research and Development Corp., the arm of the Rouse Company overseeing the new town, canceled an order of 5,000 copies because of that piece.

In a way, these articles are an updating of that original essay about Columbia — the good, the bad, the mediocre and the mundane, and sometimes even the very good. Because it is appearing first in a business newspaper — one of the few locally owned publications left in Howard County — and then at MarylandReporter.com, the news website about state government and politics that I founded and run, it will be heavy on those things I know best: business, politics, government, education, religion. But I will deal later in the series next year with other important topics, such as arts and sports, where I’ve been mostly a casual participant.

First Some History: The Land

But first we need to talk about the history. Probably more than half the people reading this have little or no inkling of how Columbia came to be. They just work in its many office parks, or bought a house here or rent an apartment because it was the right location and the right price. Given the vagaries of post office ZIP codes, some people who actually live in Columbia “new town” have addresses that say Ellicott City and Clarksville. Others with a Columbia address are holes in the Swiss cheese of Columbia’s 10 villages — out-parcels, in Columbia-speak.

Columbia was first of all about the land and what to put on it — the same question faced by Howard County’s first real developer, Charles Carroll of Carrolton, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence, whose country estate is still owned by the family and sits in the middle of more than 1,000 acres of farmland just a few miles north of Columbia. He, his ancestors and his heirs developed what was once 13,000 acres — almost the size of Columbia — by selling parcels to people like the Clarks to build a mill in 1790 and then, over the next two centuries, selling off other pieces as farmsteads and home sites.

In 1962, 130 years after Charles Carroll died and was buried in the chapel on his estate, Howard County was still a mostly rural enclave between Baltimore and Washington. Lopped off of Anne Arundel County in 1851, the county had just 45,000 people, with a few pockets of large-lot developments along two-lane Route 29: Dunloggin, Allview Estates, Atholton.

With the suburbs of the two old cities growing, and Interstate 95 about to open on its east side (and I-70 on the north later on), Howard County was ripe for suburban sprawl.

Realizing this, a Baltimore mortgage banker named Jim Rouse decided he could build not just a better suburb, but a real city that combined both city features and suburban life.

He already was constructing a planned development on an old golf course in north Baltimore — the Village of Cross Keys — but that was a village in the midst of an old city. His company also was one of the first in the nation to develop enclosed shopping malls; one of the first was Mondawmin in the 1950s, in the heart of Baltimore.

A New Look for ’Burbs

Columbia could be a fresh departure from the suburbs that Rouse’s own mortgage company had helped foster after World War II.

The machinations Rouse went through to set his plan on course make an exciting story even 50 years later: Second-hand agents, not knowing whom they were representing, bought farm after farm for a series of dummy corporations. Speculation was wild about who was assembling all this land — ultimately 14,000 acres — and why. The secretiveness was believed necessary to keep down the price of the land. Rouse lined up the Connecticut General Life Insurance Co. to finance the project.

Almost a year after the first purchase, Rouse finally announced he was planning a new town, but that proved to be just the beginning. Then came one of the most intriguing parts of the planning process. Now that the land was owned, it had to be planned, with streets and homes and shopping and schools.

In addition to the physical plan, Rouse had a higher vision. He wanted a social plan to make the new city work for people. He gathered a group of 13 experts in nearly as many fields: government, recreation, sociology, economics, education, medicine, housing, transportation, communications and family life. All were white men except for a lone woman, an expert on women’s issues.

Remember, this was 1963. The civil rights movement was coming to a head, and the feminist movement had barely started. In the Howard County of that time, the men worked, the women stayed at home (or worked on the farm) and the Negroes, some descended from Carroll slaves, went to segregated schools and restaurants. This conservative but Democratic county — Democrats were still the more racist party in Maryland till the late 1960s — had elected a group of conservative Republican county commissioners championing an anti-growth platform.

Those were the folks Jim Rouse had to pitch to for his idea of a “new town,” and the flexible zoning to make it feasible.

Four Goals

As Jim Rouse often described it, Columbia had four key goals that grew out of the social planning work group, his own experience growing up in small-town Easton, and the spirit of the times. In some lists, the goals are in a different order, but this one makes the most sense.

Goal No. 1: To respect the land. Rouse believed strongly that “there should be a strong infusion of nature throughout a network of towns; that people should be able to … feel the spaces of nature all as part of his everyday life.”

Goal No. 2: To provide for the growth of people. Rouse believed that “the ultimate test of civilization is whether or not it contributes to the growth — the improvement of mankind. Does it uplift, inspire, stimulate and develop the best in man? … The most successful community would be that which contributed the most by its physical form, its institutions, and its operation to the growth of people.”

This was embodied symbolically in the People Tree in Columbia’s town center, which was once the symbol for all of Columbia and still stands there today.

Goal No. 3: To build a complete city. Rouse explained it this way.

“There will be business and industry to establish a sound economic base, roughly 30,000 houses and apartments at rents and prices to match the income of all who work there. Provision has been made for schools and churches, for a library, college, hospital, concert halls, theaters, restaurants, hotels, offices and department stores. Like any real city of 100,000, Columbia will be economically diverse, polycultural, multi-faith and inter-racial.”

Howard County at the time had only a smattering of those institutions and none of those qualities. The schools were not considered top-notch, and they had just been desegregated, though the housing wasn’t; one of the newer developments even had covenants excluding Jews. While there was a long Catholic presence, with Jesuit and Redemptorist seminaries nearby, most of the churches were mainstream Protestant. (This was before the great ecumenical opening of the Catholic Church in the Second Vatican Council going on about that same time.)

Goal No. 4: To make a profit. This final explicit goal is often glossed over as secondary, but as Rouse would say, making a profit “brings discipline to all the other goals.” It was also important to him to demonstrate that good development focused on the other three goals could make money if other developers followed suit.

As lofty and attractive as these goals were, Rouse’s pitch was practical as well. Columbia would be a boon, not a burden, to the small county, which would at least triple in size if the town were built. The inevitable growth in Howard County’s future, he insisted, was better channeled into a concentrated area. The housing density in the new town and the business parks that would bloom there would gain revenue for the county, more than supporting the public services needed, and they would prevent sprawl.

Not a burden on the county

Columbia would have its own taxes — a lien established by covenants on every property in the new town. The lien would help pay for all the recreation and community facilities and the upkeep of the open space that would wind through all the stream valleys, with bike paths connecting every village.

In a crucial decision that later would be much debated, Columbia was not to be a separate municipality with a mayor, police, fire and public works; it would rely on the county for those services. Like all of Maryland, under state law the schools would be part of a countywide system. The roads, water and sewer would be built by the developer and then turned over to Howard County to maintain. Even its health care would be self-contained, run by a unit of Johns Hopkins medicine.

The commissioners and their constituents were skeptical but realistic. Lawyer Jim Rouse may have been a visionary capitalist, a liberal internationalist, and a social gospel Christian, but he was also an inspiring speaker and an excellent salesman. To use a word he liked to use for other people, spread out in syllables, he was “extra-ordinary.”

It did not come easy, but after months of meeting and presentations, county residents came around, and the county commissioners eventually approved the plan and the new town zoning in 1965. There followed feverish activity to build the infrastructure: lay out the roads and pave them, bulldoze the bike paths, set aside the open space, build the first buildings, construct the dams for two man-made lakes.

Then on June 21, 1967, the date now observed as Columbia’s birthday, the dam was dedicated for Wilde Lake and Columbia’s first village, named for the chairman of Connecticut General, Frazar Wilde, who enthusiastically agreed to finance Rouse’s plans. The following day “The Next America” Exhibit Center opened, and on July 1 the first residents moved in.

True Believers in the Goals

These first residents and many of those arriving in the next decade would be enthusiastic believers in Rouse’s goals — the first three, at least. It was the right time in the nation’s history to act on interracial tolerance and interfaith cooperation; and three years later, in 1970, the establishment of Earth Day recognized the growing environmental movement.

Rouse’s commitment to integrated housing may seem routine now, but in 1960s Maryland it was revolutionary.

The social goals attracted people from all over the country, especially those of a liberal bent. The Johns Hopkins commitment to a new style of health care — a health maintenance organization — came as the Medicare and Medicaid programs had just passed Congress, and Medicare was being implemented just up the road at Social Security headquarters in Woodlawn, where many of the new residents worked, including me for a year.

Some others of the new, highly educated residents worked at a then-little-known or -understood federal agency just 10 miles away at Fort Meade — the National Security Agency. The super-clandestine communications intelligence agency at that time had no sign to announce its presence. No Such Agency, some would say.

Rouse basked in the media adulation, and the praise was almost universal. There was substantial criticism of the new town’s architectural blandness, however. The homes were pretty much what you could find in any suburb, but architectural allure was not one of Rouse’s goals. He wanted market housing that would appeal to the average consumer.

Frank Gehry, now a world-renowned architect who early in his career had slapped together the Exhibit Center and Merriweather Post Pavilion, decades later would comment about Rouse: “I don’t think his taste was very good. It was penny-loafer and tweed-coat. He was a God-fearing man who didn’t have much of an art education. His idea of architecture was little cabins and cottages and it was down home, home-spun and small scale.”

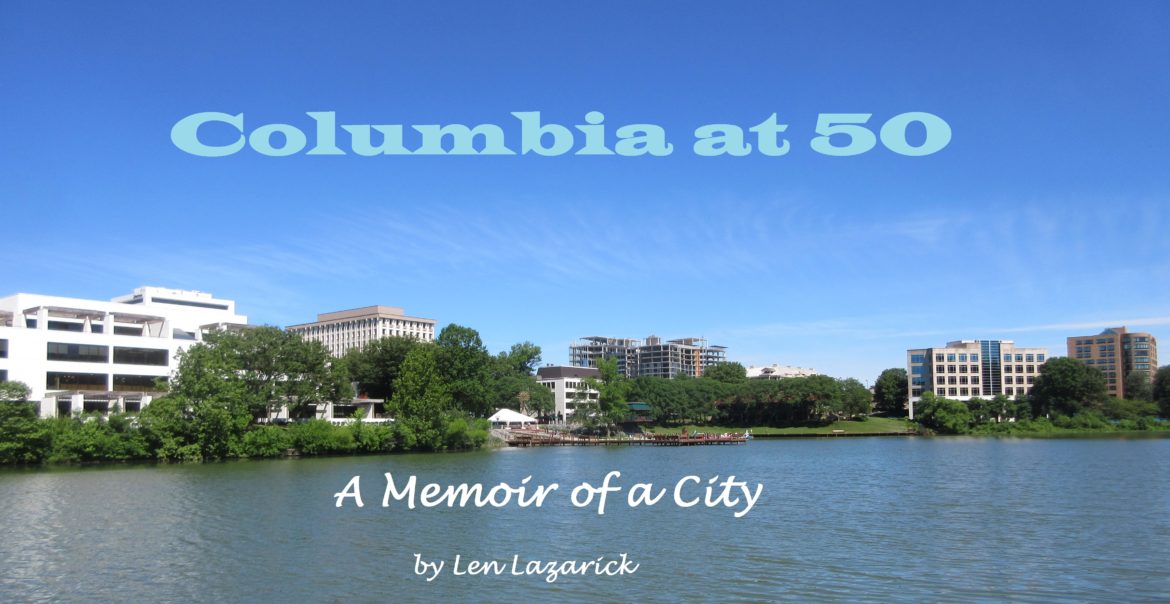

The essays that follow in this year-long series leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday — never an “anniversary” but a “birthday,” celebrated with a big cake Rouse would cut at a lakefront celebration — will flesh out how those four goals turned out and much else that couldn’t be planned or foreseen.

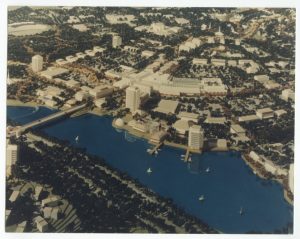

The Merriweather Post Pavilion was one of the first buildings in Columbia, built as the summer home of the National Symphony Orchestra, which did not stay long. In the distance is American City Building, obscuring both the Teacher’s Building and the Exhibit Center. In the upper left is the empty acres on which the Columbia Mall would be built. (Columbia Archives)

To Make a Profit

Yes, the Rouse Company and Columbia would eventually turn a profit, but 10 years later than originally expected. In the mid-1970s the whole project almost went bankrupt, hundreds of Rouse employees were laid off, and Columbia’s continued development required a massive infusion of cash from Connecticut General, which dispatched three employees to watch over its investment.

I began covering the Rouse Company as a business in 1975 for the Columbia Flier, along with the school board and politics. No doubt this period of pain and strain had influenced my 1977 essay that debunked the rosy-colored rhetoric of the early days. The Rouse Company malls, well-built and well-situated in mostly affluent communities, were ultimately generating more income than Columbia.

This profitability led in 2004 to the company’s sale for $12.5 billion to General Growth Properties, the largest-ever real estate deal at the time. GGP swallowed up too much real estate too soon, and burdened by debt it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2008.

The name of the once mighty Rouse Company disappeared from Columbia eight years after its founder had died, and long after he had been pushed out of its leadership. The admired white stucco headquarters Frank Gehry had designed temporarily bore the name of the Howard Hughes Corporation, the land development division that was once part of Rouse Company but spun off from GGP.

In a creative repurposing for The Rouse Company headquarters, the building was gutted to become a Whole Foods organic grocery store.

Sitting by a window in Whole Foods open dining area — a great place for a quiet mid-morning meeting — you can look out over Lake Kittamaqundi, the plaza, the fountain and the People Tree, the same view Jim Rouse had from his office that was once just one floor above.

The only remnant of Rouse himself are two statues near the water of Jim Rouse and his brother Bill, who died at age 61. They were commissioned not by the company that bore his name, nor the Columbia Association nor Howard County, but by his nephew-in-law, Claiborn Carr III. Clai was once married to Bill Rouse’s daughter Cathy and worked for Rouse in sales and marketing, sometimes driving “Uncle Jim” around as he gave personal tours. Clai later developed office buildings in Columbia with Cathy’s brother Bill Rouse, at Rouse & Associates.

After one of the statues fell down at the Symphony Woods office building, the sculptures sat in a closet for years till they were finally resurrected to their place of prominence. Most people must wonder who the men are and why they are there.

To Respect the Land

Looking out his office window and from his modest modern home on the shore of Wilde Lake, Rouse could see a project that tried to protect the environment — as that goal was understood 50 years ago. There are many more trees now in Columbia than there were when the open farmland first was purchased; 10,000 were eventually planted, since Rouse insisted on landscaping on the lots it sold. The Middle Patuxent Valley is now a permanent nature preserve through the persistence of a naturalist who lived there — in exchange for greater densities elsewhere in the new town.

If planned today with the environment in mind, the streets might be narrower to reduce impervious surfaces — but where would people park those unplanned extra cars? There would be tighter controls on stormwater runoff, as well.

The ideals that informed Columbia’s design have now become standard in housing developments in Maryland and nationwide, with planned open space running through the stream valleys offering plenty of habitat for wildlife. You’re likely to see more animals on a Columbia cul-de-sac that honors the contours of the land than you might in a national park. The white-tail deer just love Columbia and its gardens, and so do the foxes, who eat the mice and bunnies, but perhaps not the skunks. A mother skunk and her babies once camped out under our front steps for several weeks before the critter catcher removed them.

To Provide for the Growth of People

The original planning for Columbia provided for those institutions that might naturally evolve in any new development, but only after the residents had moved in. In the traditional pattern still seen today in other housing developments, farms would be converted to housing, then over time would come the stores, the churches, the schools, the libraries, the community buildings, pools and tennis courts. Rouse thought this pattern backward. Why not provide for these institutions from the start?

So as Columbia residents moved in or shortly after, they found shopping centers, pools and community centers, an interfaith center for use by multiple congregations, and land set aside for schools if not the schools themselves.

“The most remarkable thing about Columbia is that it is remarkable at all,” Rouse told a congressional committee in 1972. “It can and should be replicated and vastly improved upon in smaller and larger communities over and over again throughout America.”

That was not to be and rarely on the scale of Columbia, with the exception of such places as Woodlands outside Houston, inspired by Rouse in 1974 and now managed by Howard Hughes Corp. In many developments nationwide, Columbia’s influence can be seen in the proliferation of cul-de-sacs, rather than the old grid pattern of streets, and the group mailboxes that were an innovation the post office pushed in Columbia to reduce costs. Rouse spun their inconvenience as a way for neighbors to gather and chat, enhancing community life — certainly a stretch of the imagination.

Where’s the City?

As we look out Rouse’s window, we may call this downtown, but what Columbia still lacks after all these years is density and a feeling of urbanity. The goal was: “To build a complete city, not just a better suburb,” said Rouse. Yet, it is hard to call it a city with downtown half empty.

The 1970s oil crisis, caused by an Arab oil embargo after the 1973 war between Israel and its neighbors, and a recession with high inflation, devastated Columbia’s economic model. Housing sales plummeted, as did sale of land to build those houses.

Columbia had a bus system run by the Columbia Parks and Recreation Association — the Columbia Association, or CA for short (not the abbreviation for California or the medical shorthand for cancer). But the town was and is designed around the car. The oil embargo that created rationing and gas lines restricted driving.

The plan from the start was that as the town grew with apartments, townhouses and single family homes, the land at its core would become more valuable, and more expensive land prices drives buildings upward, creating urban density.

Prior to the economic troubles, the original economic model envisioned Columbia’s full development in 1980.

Thirty-six years later, that final phase of urban development is just beginning to happen. High-rise and mid-rise office buildings are again sprouting up on Little Patuxent Parkway; new urban-style apartment blocks are underway near the mall. The arts area around Merriweather is being redeveloped and enhanced. The downtown of a new city envisioned 50 years ago has finally been kicked off.

In a speech in 1979, in a rare admission of imperfections, Rouse said, “There are a hundred ways that Columbia is deficient, lots of things that are wrong, but there are a thousand ways in which Columbia is far beyond anything that could have happened unless we had worked toward an ideal.”

Next month: Columbia at 50: The Business of Columbia

Len Lazarick has lived and worked in Columbia as a journalist for more than 40 years. He is currently the editor and publisher of MarylandReporter.com, a news website about state government and politics and a political columnist for The Business Monthly. He has also worked as an editor at Patuxent Publishing, the Washington Post and the International Herald Tribune and Annapolis Bureau Chief for the Baltimore Examiner. This article is copyright protected by Len Lazarick. The Baltimore Post-Examiner was granted permission to publish this article.

MarylandReporter.com is a daily news website produced by journalists committed to making state government as open, transparent, accountable and responsive as possible – in deed, not just in promise. We believe the people who pay for this government are entitled to have their money spent in an efficient and effective way, and that they are entitled to keep as much of their hard-earned dollars as they possibly can.