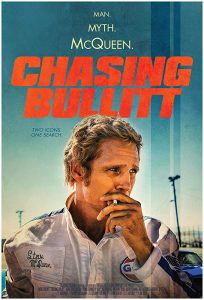

Chasing Bullitt: Fiction-fueled ride fails film legend Steve McQueen

Andre Brooks portrays film icon Steve McQueen in Chasing Bullitt. (Toe Pictures)

There was a time, not all that long ago, when matinee idol Steve McQueen was arguably the most famous movie star in the world. Following a series of unforgettable roles in such classics as The Blob, The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape, The Thomas Crown Affair and Bullitt, McQueen embarked on a project which nearly broke him – a European car race film, called Le Mans. He returned to the states badly bruised from the experience, facing an angry studio, a doubtful public, a huge tax bill, and a crumbling marriage. How McQueen navigated this nadir is the basis for a new biopic, titled Chasing Bullitt.

At least, that’s what the producers of this painfully misguided effort would like us to think.

Chasing Bullitt.

(Giovanna Carcione Lawson)

Chasing Bullitt is not so much a biopic as it is a pop-psychology fantasy. The film takes several spurious detours with McQueen’s life story, opting for a tedious narrative when the truth would have been far more compelling.

Chasing Bullitt was released last week via video on demand – presumably because no one wanted to touch it with a ten-foot dipstick. The movie did have a 2018 film festival incarnation, under the working title GT 390.

Both monikers only hint at the head-on collision which is about to take place.

At first, it seems strange that a biopic about Steve McQueen would be a hard sell to movie houses – considering the timely subject matter, some pleasing vistas, and an adequate leading man who strongly resembles McQueen. Then too, there’s the hook of the troubled star’s iconic ride – the Ford Mustang GT 390 from the 1968 movie Bullitt. Yet none of these matter if you don’t have a solid story to tell.

Here is where the engine-knocking begins.

As the action unfolds, we find McQueen (portrayed with an ever-furrowed brow by former Canadian boxer Andre Brooks) test driving what appears to be the muscled-up Mustang from Bullitt. We discover Steve’s ride is not that particular car, but rather a much tamer clone, which Warner Bros. presented to their brooding star upon his return from filming Le Mans in France.

(courtesy Toe Pictures)

After a few laps around the track, the mild rumble of the Ford’s 302 engine gives way to the piercing yowl of McQueen’s raging agent, Freddie Fields (Dennis W. Hall.) Freddie informs his client that the fake Mustang is the least of his worries. McQueen is in financial straits and needs a hit movie to put him back on top.

McQueen reluctantly agrees to pick a film project from an impressive list of titles, provided that Fields can first come up with the name of the person who now owns the original Bullitt Mustang.

With that charge, we should all be off to the races.

It’s a race all right – from one lap-losing pit stop to another.

After some steep bank turns with Steve’s long-suffering wife; a disconcerting shrink; and a pleasing but pesky hitchhiker (who just can’t to stop using his full name – Steve McQueen) the first real spinout occurs in a Cuban jail. There McQueen is beset by soon-to-be-ousted dictator, Fulgencio Batista (Anthony Dilio.) What follows plays like an extended exercise from an acting class.

We know that Batista was cunning and ruthless, but must the audience be held hostage, as well?

Brooks and his furrowed brow are no help here, and even with a sudden shift in mood, the scene feels like it goes on forever.

But wait – did McQueen really land in a Cuban jail and trade Lucky Strikes with Batista? Not according to one biographer, who told me that while the prison escapade was real, McQueen actually cooled his heels by sharing some cheese with one of the jailers.

Perhaps this is where it should be noted that Chasing Bullitt was written, produced and directed by the same person, Joe Eddy (Coyote). For some reason, much of what appears onscreen is pure fantasy. Can you do that with public figures in a quasi-historical context? Apparently you can. But had a third party fact-checked the script, the project may have never gotten off the ground.

The literary license is lamentable, but the direction is what really does this effort in. It’s bad when the viewer is the one who keeps yelling “CUT!”

There’s a way, for example, to direct an ugly encounter in a wrecked relationship without needlessly protracting the grueling display. And there’s a way to show a moment of amorous abandon in the desert, without making the audience wish the players would just get a room already. Heck, there’s even a way to present Dustin Hoffman in all of his neurotic method-acting splendor, (though I think Hoffman has pretty much covered that ground himself in everything he has done since those early Volkswagon ads.)

The actors in the aforementioned examples (Augie Duke as McQueen’s pitiable wife Neile; Alysha Young as a feisty hitchhiker named Sula; and Jason Slavkin as “Dusty”) manage to make the most of their roles – even as they navigate nettlesome dialogue and the ever-drifting direction. But the scenes never get out of first gear – save for one tongue-happy kiss which lingers in second gear long after the red flag should have been waved.

The most painful off-ramps in the film are those where McQueen unloads to an unnerving therapist (Ed Zajac.) Forget the doctor’s mortician-like demeanor, the muted “epic” background music, and fitful flash-back bows to Fellini (yes, THAT Fellini) – what’s with the wandering camera close-ups of the therapist’s injured forefinger?

(courtesy Toe Pictures)

Not quite as bizarre, but nonetheless badly executed, is a scene where McQueen’s alcoholic mother Julian (Jan Broberg) appears as the back-seat driver from hell – or wherever it is that bad mothers go once they finally leave life’s cocktail lounge. The dialogue here should be front and center, since Steve was the product of a broken home, but the camera floats around Julian’s face, as if the fake Mustang has blown its shock absorbers.

Aside from Sula’s smile and a few tender moments with Neile, the only endearing part of the film occurs near the end of the curious car-quest, when McQueen meets a hurting teenager named Rodney (Chantz Simpson.) Yet, no sooner do we relax in the relative comfort of a cogent chat than Eddy finds a way to mar the moment with a disappointing dose of macho manipulation.

A title-card epilogue fills in a few details of the final decade of McQueen’s life before ending the madness with an eye-rolling expletive – a regrettable way to close an exploitive endeavor.

The professionalism of the better actors notwithstanding, I can’t imagine why anyone associated with this horrid hodgepodge would want the title to appear on their resume. And I say that as someone who was personal friends with an actor who worked for Ed Wood.

Steve McQueen was an American icon – a troubled youth who rose to the top – only to find that life beyond fame, fast cars, and faster women has a far deeper meaning. His true history should be told with all of its heartache, hedonism, and hope, and perhaps someday Hollywood will tell it.

But be forewarned – Chasing Bullitt is definitely not that tale.

Running time is a sputtering 90 minutes.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”