Democrats should come out swinging for the midterms

If Democrats go big this November, they won’t have to go home

It’s been a week of mixed news for Democrats hoping to hold down their losses in the House and Senate this November.

First, a McClatchy-Marist poll shows the GOP taking a five-point lead on the House generic ballot, at 43-38. That was followed by polls in Kentucky and Georgia showing Republicans inching ahead of their Democratic opponents there. On the other hand, a Fox News poll released Wednesday showed Democrats leading 46-39 on the generic ballot, surging from a mere two-point lead last month. And with polls showing Senator Kay Hagan stabilizing her modest lead in North Carolina, Democrats probably have a clearer path to protecting their majority than they had last June.

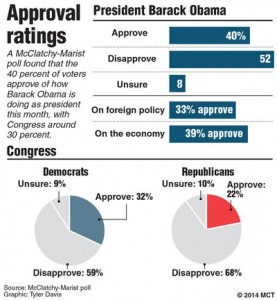

Even so, the overall picture is pretty grim from Democrats’ perspectives. President Obama’s numbers are bleak, and Republicans are gunning for Democratic-held seats in states he lost when he was more popular. Alaska, South Dakota, West Virginia, Arkansas, Louisiana, Montana, and North Carolina all feature Democrats who are having to walk a political tightrope between creating just enough space between themselves and the national party to appeal to the conservative-leaning voters they’ll need to reach 50 percent, and alienating too many of their base voters to the point that they stay home and let their nominees get washed away in miserably low turnout. And as they manage these political acrobatics, they’ll have to do so with SuperPACs raining hundreds of thousands – or more often, millions – of dollars in attack ads on their heads.

Even so, the overall picture is pretty grim from Democrats’ perspectives. President Obama’s numbers are bleak, and Republicans are gunning for Democratic-held seats in states he lost when he was more popular. Alaska, South Dakota, West Virginia, Arkansas, Louisiana, Montana, and North Carolina all feature Democrats who are having to walk a political tightrope between creating just enough space between themselves and the national party to appeal to the conservative-leaning voters they’ll need to reach 50 percent, and alienating too many of their base voters to the point that they stay home and let their nominees get washed away in miserably low turnout. And as they manage these political acrobatics, they’ll have to do so with SuperPACs raining hundreds of thousands – or more often, millions – of dollars in attack ads on their heads.

That’s a daunting picture for any liberal observer. Throw in the fact that these seven states total just under seven percent of the country’s population, and Democrats have even more reason to be depressed. Republicans can take the six seats they’ll need to win the Senate this year just by appealing to a few million rural, anti-Obama voters.

And if Democrats can hold down the GOP’s gains enough to hang onto a diminished Senate majority, what does that mean? The short answer is, a lot. Beyond the President’s ability to see his judicial nominees confirmed, which is huge enough, the President’s last two years are at stake with the Senate majority this November. As hard as it may be to believe, this era we live in that’s characterized by scorched-earth political maneuvering, shutdowns, and default threats will be even worse with Republicans fully in control of Congress. If you think the GOP can’t make more mischief and sabotage with Senate control as additional leverage, you don’t know today’s Republican Party.

But that argument isn’t enough. The sentiment that will be shared by most Democratic voters who dutifully trudge to the polls this November–“We can’t let it get any worse”–just isn’t a winning theme.

Looking at the congressional races Democrats are running, it’s hard not to walk away with the sense that they’ve sunk one step below playing not to lose. For months now they’ve been playing to lose as little as possible. It’s a midterm election, the thinking goes. Our side doesn’t really turn out, their side is revved up. Let’s play to lose only the two or three seats that are already goners, and when we pull that off, it’s a good night.

The problem is, that’s not a good night for their voters. The people Democrats need to show up to save the day in November, the people who made up a majority of the electorate in the last two presidential elections, are also the people who have been crushed and demoralized the most by what’s been happening, or more accurately not happening, in Washington.

The collapse of immigration reform

The failure to even bring up gun control for a vote in the wake of the Sandy Hook shootings. The long list of reforms, many of them popular, that John Boehner’s House of Representatives won’t even allow a vote on. All of these failures and depressing inactions don’t just stop progressive initiatives in their tracks. They also dampen the turnout of key Democratic constituencies in November, making the Republican obstruction bad policy but good politics.

So the Democratic base voters, who had their stratospherically high expectations for the Obama years crushed by unprecedented obstruction by Mitch McConnell and others, could be forgiven for looking at the overall picture in Washington and wondering if things will really be any better if they block out half an hour (or potentially several hours, depending on lines) to vote on a chilly Tuesday in November.

It’s taken for granted that Boehner and his cohorts are here to stay, thanks to a moribund Democratic base will be out-hustled and out-voted by perennially-enraged Tea Partiers.

But does that have to be the story?

Imagine—if you can— a Democratic Party that hits the midterm trail in a fighting, feisty mood. Try to picture red-state Democrats who aren’t apologizing for their votes to provide the poorest and most vulnerable of their constituents with health care. Most of all, think about what a Democratic Party that was united would look like going into November. And not just one that’s united by caution, either, but one that touts its achievements, celebrates its story of the last six years, and lays out a bold and unapologetic progressive vision to voters.

Think it’s a pipe dream? Maybe. But at the risk of sounding like the wide-eyed 23 year-old liberal that I am, let me explain to you why Democrats have far more to gain this November from owning and embracing liberalism than they stand to lose from it.

Probably no one in America understands both how to lose and win midterm elections better than Bill Clinton. His party’s loss in 1994 resulted in the first Republican Congress in 40 years, opening him up to a universe of gridlock and political hurt. In 1998 it was supposed to be a similar story; his party’s voters were demoralized, while Republicans smelled blood. But the opposite happened. There was no net change in the Senate, while Democrats actually gained five seats in the House, marking the first midterm gain for an incumbent President’s party since 1934.

“It happened in 1998 and again in 2002,” Clinton later wrote in his autobiography, “My Life”. The party that had a message won, he noted – hard-line support of President Bush in the wake of the 9/11 attacks in the latter, an anti-impeachment message from a popular President’s party in the former.

That was Newt Gingrich’s permanent contribution to American politics, Clinton realized. Before his 1994 Contract With America, midterms had never been nationalized, and they’ve been nationalized ever since. Local issues still matter, and the successful candidates know how to play them. But relatively few voters cast their votes based on which candidate could get federal dollars used to build a factory in the district, or even put his or her name on a piece of landmark legislation that the voters approved of. No, the most powerful factor voters weigh for candidates these days is how they feel about the candidate’s party, and especially the party’s national agenda.

Elizabeth Warren used this knowledge with deadly effect in her uphill 2012 Senate race against the personally popular Scott Brown. In his two years in the Senate, Brown had done what he needed to do to cultivate a moderate image, essential in a state where Democrats outnumber Republicans two to one. He was pro-choice, and the Senate’s Republican leadership often cut him some slack in voting against the official party line occasionally, reasoning that he was from Massachusetts, after all. But Warren wouldn’t let voters forget about the “R” in front of his name, or the impact that sending another Republican to the Senate would have nationally.

“If Republicans take control of the Senate, Jim Inhofe will take charge of a committee that oversees the Environmental Protection Agency,” said Warren invoking the unknown Oklahoma senator. “That’s a man who calls global warming a hoax. A dangerous man.” A man, she noted, who should not be anywhere near a position of authority over the EPA.

The logic was undeniable: The Senate race was about more than Scott Brown or Elizabeth Warren. It was mainly about which party would control the Senate. And that will be true of every Senate race in 2014, whether Democrats like it or not.

And that’s why Democrats might as well own their party’s agenda, with only a few caveats here and there. True, Natalie Tenant of West Virginia and Allison Grimes of Kentucky can’t exactly give full-throated endorsements of the Obama administration’s policies toward coal.

But what they can do, and what every Democrat should do, is champion the many issues that unite the party and are popular with voters. In West Virginia, Kentucky, and everywhere else, those issues are raising the minimum wage, passing immigration reform, and yes, gun control.

Here’s a number for you to think of when you think of gun control: 81%. That’s the level of support that was recorded among Republicans for the bill the Senate drafted that would expand background checks. And yet, Senate Republicans killed the bill with a filibuster, with four Democrats joining the opposition. “A shameful day in the Senate,” President Obama called it. He noted the sweeping support for the bill, and asked rhetorically, “Who do you think you’re representing?”

The answer is, the far-right fringe. These senators are terrified of the NRA, just as they’re afraid of the Tea Party and the 20 percent of this nation that makes up the far right and votes in Republican primaries. John Boehner’s House and Mitch McConnell’s minority caucus don’t represent America, and they don’t even represent mainstream Republicans. There’s a way for Democrats to hold them accountable for this.

In an election where Congress scores lower popularity than Vladimir Putin, Democrats need to point out that the events of the last four years don’t have to keep recurring. The debt ceiling fights, the shutdowns, the brinksmanship, and the very reality of a Congress that doesn’t seem beholden to everyday Americans can all be voted away at the ballot box. Democrats just need to portray themselves as the vehicles nationally to end this insanity.

Because insanity is exactly what defines this situation. When House Republicans don’t listen to business leaders who urge them to pass an economically beneficial, deficit-cutting immigration bill, that’s insanity. When the Senate Republicans brush off supermajority opinion in the United States to kill a bill on expanded background checks in gun shows without even bringing it up for a vote, that’s insanity. And when they threaten to torpedo the full faith and credit of the United States unless their policy demands are met, it’s a whole new level of crazy.

The depressing thing is, voters are starting to get used to it. And that’s why Democrats running this year should drive home a new and novel message: Things don’t have to be this way.

What if all 398 Democrats running for Congress this year, both incumbents and challengers, assembled on the White House lawn to sign a Democratic version of a Contract With America? It wouldn’t have to be some liberal wish list. Democrats should unite and put their signatures behind something that’s big on policy, but has a special emphasis on one promise: that they will end the brinksmanship in Washington, the galling default threats, and the specters of government shutdowns.

On immigration reform, Democrats can pull a coup on two fronts. By promising to bring the bill that passed the Senate up for a vote in the House, they’ll fire up a key voting block they’ve come to rely on while piquing the interests of business leaders. It’s a strategy that would mobilize their base everywhere, but be especially potent in the Hispanic-heavy states of Colorado, Florida, and increasingly, North Carolina.

On minimum wage, Democrats enjoy a position that’s close to a slam dunk. Raising the minimum wage polls extremely well, and people aren’t buying the arguments of congressional Republicans that it just reduces employment. Democrats should promise as a block to raise the minimum wage if they take the House, spelling out the proposed increases over time to reduce the uncertainty for business leaders as they adjust.

Then there’s gun control. The proposed background checks that were killed in the Senate might seem modest in scope, but to millions of Democratic voters who might otherwise choose to sit out these elections, the subject is incredibly poignant. I can see the ads right now: a map of America, with red Xs showing the spate of shootings that have taken place since Sandy Hook, giving way to an image of Mitch McConnell scowling as a narrator describes how he led the effort to kill expanded background checks in the crib. That, coupled with Grimes’ frequent observations of how McConnell has blocked minimum wage increases while becoming a millionaire in his time holding public office, should go a long way towards showing Kentuckians exactly who their senior senator is beholden to.

Then there’s gun control. The proposed background checks that were killed in the Senate might seem modest in scope, but to millions of Democratic voters who might otherwise choose to sit out these elections, the subject is incredibly poignant. I can see the ads right now: a map of America, with red Xs showing the spate of shootings that have taken place since Sandy Hook, giving way to an image of Mitch McConnell scowling as a narrator describes how he led the effort to kill expanded background checks in the crib. That, coupled with Grimes’ frequent observations of how McConnell has blocked minimum wage increases while becoming a millionaire in his time holding public office, should go a long way towards showing Kentuckians exactly who their senior senator is beholden to.

And finally, Democrats can promise to end the threats of defaults and shutdowns. “There are going to be issues where we disagree with our Republican friends, issues where we don’t get our way,” they can say. “But there’s one thing you can take to the bank: We will never insist that government pass our policy goals in exchange for us voting to honor the credit of the United States, or keep the government from shutting down.”

Those are powerful messages that Democrats should keep pushing on the campaign trail. Popular in red states, popular in blue states, these proposals can shake their base voters out of their funk and motivate them to show up at the polls. It could mean a rising voter tide that lifts all Democratic boats.

I understand how challenging the math is, especially in the Senate. And it’s common knowledge that a lot of these Republican House incumbents have inoculated themselves from public opinion thanks to gerrymandering. There are a lot of environmental factors that Democrats can’t do anything about.

But they can do something about their message. They can celebrate the progress that’s been made over the last six years, working overtime to make sure every voter in America knows that the economy, which just posted its sixth straight month of jobs gains numbering over 200,000, is starting to hum again. They can point out that since the implementation of Obamacare, the percentage of uninsured people in America has fallen dramatically. And they can go on the offensive like happy warriors, letting people know that things would be even better with an immigration bill and without the economic shock waves triggered by every crisis Boehner’s Congress manufactures.

Or they can curl up in the fetal position, downplaying every accomplishment of this administration and playing up their differences, apparently under the delusional belief that they can attract some of the other side’s voters with some public remarks castigating Obama. No, those voters, who will probably number around 40% of the midterm electorate, are hell-bent on punishing Obama, and that means voting out any and all Democrats they find on the ballot.

And the other 60 percent? Besides the Democratic base itself, they’re people who are disgusted with Washington and generally disapprove of the job the President’s doing, although many still want to believe in him. They’re open to suggestions for how to close the chapter on a Congress that may be the best argument against democracy that history’s ever produced. And if they’re given a clear reason to vote Democrat, they will.

Playing defense and going bold are the party’s two choices this November. It may be that neither of them leads to victory. But on every political front, going bold makes more sense. And in a country that continues to pay the price of having a broken Congress every day, it’s the path that feels right.

William Dahl is a recent graduate of The College of William and Mary, where he majored in Government and studied abroad in La Plata, Argentina. He has worked for community foundations in Argentina and Miami dedicated to community engagement and prosecution for human rights abuses. A native Virginian, he moved to Baltimore in 2013 to join a financial research firm, where he enjoys being able to write on the side.