$50 billion in unfunded state and local retirement benefits, study says

By Len Lazarick

The money Maryland’s state and local governments have failed to set aside to fulfill pension promises made to teachers and employees has ballooned to more than $22.5 billion over the past five years, a new report has found.

The money Maryland’s state and local governments have failed to set aside to fulfill pension promises made to teachers and employees has ballooned to more than $22.5 billion over the past five years, a new report has found.

But the counties that run their own pension systems are in much better shape than the state of Maryland, with the exception of Prince George’s County.

The most under-funded retirement benefits continue to be health insurance for these retirees, which amount to $28 billion for state and local governments. Only a handful of county governments have tried to sock money away.

Those are some of the findings of a new report titled “Perpetual Shortfall” from the Maryland Public Policy Institute written by Gabriel Michael, a senior fellow and a doctoral candidate in political science at George Washington University. The institute has a free-market orientation, and has been a persistent critic of government pension systems.

“I hoped to gather together all in one place” all the financial reports from the jurisdictions, Michael said. “No one has actually done that.”

Retirement agency disputes findings

Told of the major findings of the study, the chief of the State Retirement Agency said much of it was old news. The study disregarded fixes made in pensions for state teachers and employees in 2011, and reform of funding mechanism passed just this year, he said.

“While liabilities are expected to grow in the next few years, based upon all the actions taken, the liabilities are expected to begin declining in FY 2017 and will continue to do so each year thereafter,” Dean Kenderdine, executive director of the State Retirement Agency, said in an email. “The system expects to be 80% funded by FY 2024.”

Michael said the underfunding of pensions “has been going on for a long time. Yes, we had some reforms in 2011 but those kinds of reforms tinkering around the edges are not going to be enough.”

“The root cause is that political leaders are unwilling or unable to consistently allocate the required funding for pension systems on an annual basis,” Michael says in the report. “In theory, properly managed defined benefit pension s can provide secure and relatively generous retirement income to public employees at a low cost to the public. In practice, entrusting proper management of long-term fiduciary funds to political leaders is a recipe for disaster.”

Overall, Maryland pension system is 64%, and most counties in the state at 70% or 80%. But Prince George’s County pensions for police, fire, corrections and sheriffs are funded at the 52% to 58% level, with a $871 million unfunded liability, nearly a third of the total liabilities combined for all the counties that run their own pension systems. (Six counties and many municipalities are part of the state pension system.)

Little money put aside for retiree health care

Little money put aside for retiree health care

Maryland governments have been putting virtually nothing away for other post employment benefits (OPEB), principally health care and prescription drug coverage. But unlike pensions, which generally cannot be changed after they are earned, retiree health benefits can be. That’s what the state did in 2011, reducing coverage and increasing the share paid by the retirees.

That reduced the state’s unfunded liabilities from over $15 billion to less than $10 billion. Also at that time, the legislature at the urging of Gov. Martin O’Malley increased the employee contribution to their pensions from 5% of their salaries to 7% and increased the retirement age and other pension eligibility requirements. State workers and teachers also pay into Social Security. Those changes came despite fierce opposition by public employee unions.

In a repeat of criticisms made in previous MPPI studies, Michael also said the pension funds “rely on unrealistic assumptions. Most pension funds assume average rates of return that are too high given historical experience.”

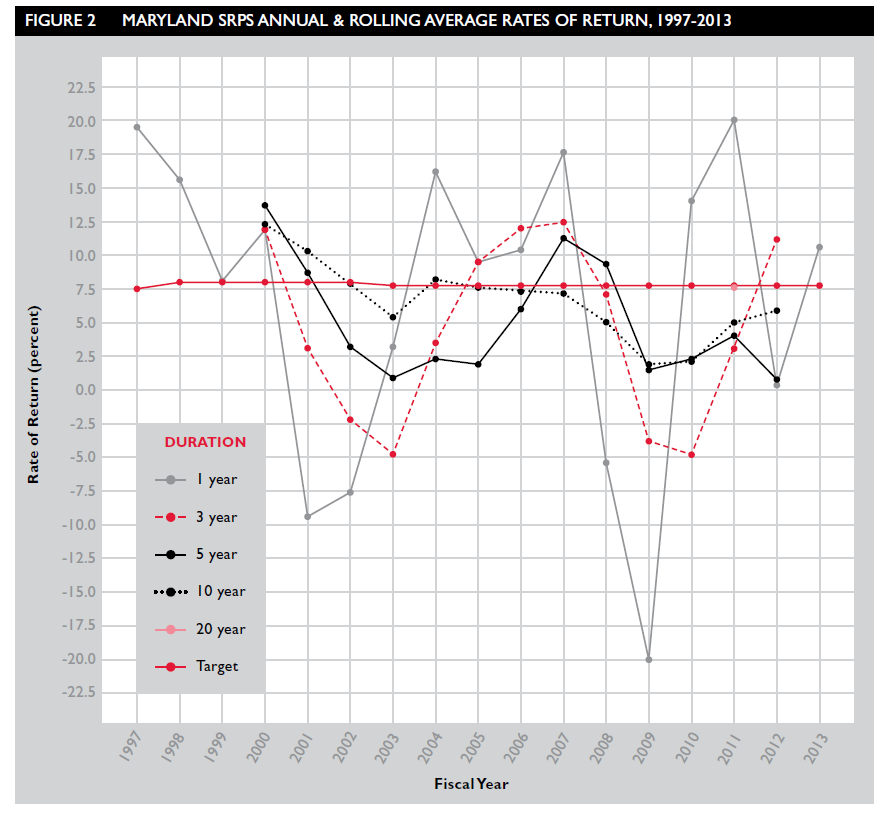

Maryland has assumed a 7.75% rate of return on its assets, currently at $40 billion, but the board of the State Retirement and Pension System reduced that to 7.55% over the next four years. Reducing the assumed rate of return increases the amount of money the state must put in every year to make up for reduced earnings.

Michael produces the graph above that shows “annual rates of return fluctuate wildly.”

He said the 10-year averages are more important. “In nine out of the 10 fiscal years since 2002, the 10-year average rate of return for SRPS has failed to meet the 7.75% assumption,” he said.

And the 20-year average in 2011 is 7.6%, below the target as well.

“Chasing unrealistic rates of return has led pension funds to increasingly turn to opaque, expensive and risky alternative asset classes,” such as private equity (stock in companies not sold on the open market) and hedge funds.

Kenderdine said investing in private equity and hedge funds has protected the state from bigger losses in the stock market.

For recent MarylandReporter.com stories related to pensions, click on this link.

MarylandReporter.com is a daily news website produced by journalists committed to making state government as open, transparent, accountable and responsive as possible – in deed, not just in promise. We believe the people who pay for this government are entitled to have their money spent in an efficient and effective way, and that they are entitled to keep as much of their hard-earned dollars as they possibly can.