Vincent van Gogh and the ‘Roderick Usher’ Syndrome

In a recent article it was argued that Edgar Allan Poe and his wife Virginia suffered from chronic poisoning by illuminating gas, when they lived in New York City from 1844 till 1846.

This was caused by toxic components of the gas, such as compounds of heavy metals and the carbon monoxide from the combustion process. But Edgar Allan Poe and his wife were certainly no exceptions, because this type of chronic poisoning by light-gas was quite common in cities where gaslight was used in houses and offices. The sickening physical and psychic symptoms that were caused by this gas were known and familiar, although their cause remained a mystery.

However, this mysterious disease, disappeared in a short time after the introduction of electric light at the beginning of the 20th century, and it was soon forgotten and never properly researched.

But in the art and literature of the 19th century this ‘disease’ sometimes plays a major role, like in Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher, where Roderick Usher suffers from many of the severe and typical problems that are caused by carbon monoxide: depression, anxiety, undefined fears, restlessness, paranoia, agression, hypersensitivity to light and sound, to name a few.

This toxicity was not restricted to gaslight alone, because paraffin lamps, wood furnaces and fire places also emitted huge quantities of carbon monoxide and caused the same health problems in ill-ventilated spaces.

In fact, chronic poisoning by combustion fumes from gaslight and otherwise, was so common that special hospitals were created for severe psychic patients who were diagnosed as hysterics. One of these, the Hôpital Salpêtrière in Paris, is still famous from the painting A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière, that was made in 1887 by André Brouillet (1857-1914). In this almost life-sized painting a hysteric woman is shown to a group of helpless medical experts who clearly don’t know what to do. The poignant and sad fact is that this painting also shows the gaslights at the wall, that were the unknown cause of all this misery.

And besides the fact that Princess Diana died there in 1997, this hospital is also known from the historic novel Blance and Mary (2004) by the Swedish author Per Olov Enquist, because the main character, the hysteric Blanche Wittmann, is admitted there at the end of the 19th century. She and thousands of other women were locked up there at that time, in the vain hope to be cured from their problems, in a gas-lit ‘hospital’ that only made matters worse. Due to the gaslight, the Salpêtrière was almost as ill-doomed to its inhabitants als Poe’s House of Usher!

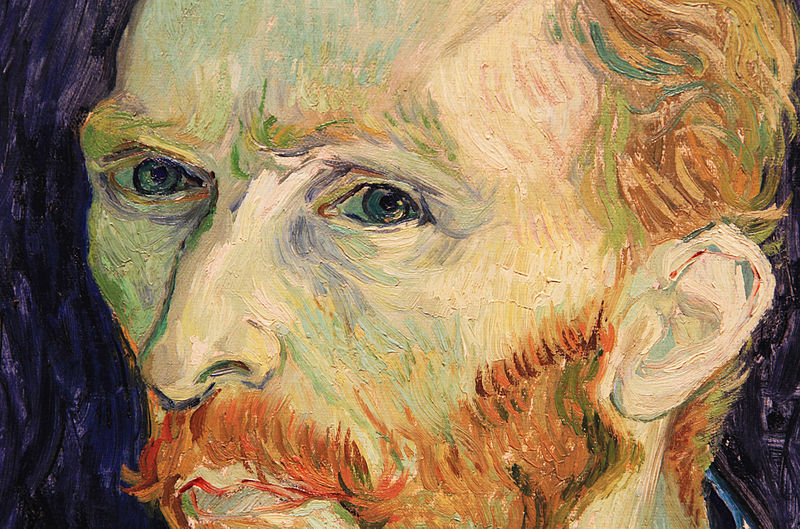

Another evident victim of the Roderick Usher Syndrome’(who, after all, was one of the first well-described cases), was the famous Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890). He was a born artist, but also a sensitive and unstable person who experienced several mental crises and nervous breakdowns during his life. Since his death medical experts and psychiatrists have suggested some 30 different diagnoses for his psychic problems.

But it stands to reason that a man who has mental and nervous problems, who is a drinker of absinthe and who suffers from malnutrition, is also especially sensitive to the toxic effects of chronic poisoning by carbon monoxide. And the fact is that Van Gogh’s two worst and final years of his short life began after he installed gaslight in his home at Arles, because he wanted to work during the evening and night. But also outside of his house he was often exposed to gaslight in the bars and café’s that he frequented and even painted. In paintings from his period at Arles, like Night Café and Café Terrace at Night the radiant gaslights are clearly present. Also the homely painting Gauguin’s chair shows a bright gaslight at the wall of the house at Arles.

But this constant exposure to gaslight at home and outside gradually pushed him over the edge, and his psychic condition worsened considerably during the winter of 1888-89. In December he started to quarrel with his good friend and house-mate, the painter Gauguin, who left soon after that. Van Gogh also began to hear sounds that were not there, which caused him to cut off one of his ears.

And his eyes became abnormally sensitive to light, also a common symptom of chronic carbon monoxide poisoning, which probably caused the brilliant and radiant lights and stars in the paintings of his last two years. During January and February of 1889 he was alternately in a hospital and at home, while suffering from “hallucinatons and delusions of being poisoned.” But he wasn’t hallucinating about that, his poisoning was real.

In March 1889 he was removed from his house after complaints from neighbors about that madman and he was eventually transferred to the hospital at St. Rémy. It was the beginning of his last year, during which he suffered from moods of undescribable anguish, hallucinations and visionary ecstacy, which, paradoxically, helped him to produce his most fascinating and expressive paintings. But all the time he had to stay indoors, in rooms and corridors that were lit by gas and paraffin, as is evident from the paintings and drawings that he made, so he never regained his health.

In February of 1890 he experienced another serious relapse, which fits the symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning, because winter is of course the worst season. In May he was transferred to a place near Paris, where he was closer to his beloved brother Theo. But recovery from carbon monoxide poisoning takes many months and Vincent van Gogh was beyond help. On 27 July he shot himself and he died two days later.

One can only wonder what would have happened if Vincent van Gogh had been allowed to slowly regain his health in a rural and gas-free environment, like Edgar Allan Poe did in Fordham. Poe eventually produced his best work there, but unfortunately we will never know what Van Gogh still had in store for the world.

UPDATE: We were informed that the idea in this text was first brought forward in 1999 by the American environmental engineer Albert Donnay. An interview with Mr. Donnay was published in 2001 in The Baltimore Sun. René van Slooten was not aware of Mr. Donnay’s work and regrets if this publication caused him any inconveniences.

René van Slooten is a leading ‘Poe researcher’, who theorizes that Poe’s final treatise, ‘Eureka’, a response to the philosophical and religious questions of his time, was a forerunner to Einstein’s theory of relativity. He was born in 1944 in The Netherlands. He studied chemical engineering and science history and worked in the food industry in Europe, Africa and Asia.The past years he works in the production of bio-fuels from organic waste materials, especially in developing countries. His interest in Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘Eureka’ started in 1982, when he found an antiquarian edition and read the scientific and philosophical ideas that were unheard of in 1848. He became a member of the international ‘Edgar Allan Poe Studies Association’ and his first article about ‘Eureka’ appeared in 1986 in a major Dutch magazine. Since then he published numerous articles, essays and letters on Poe and ‘Eureka’ in Dutch magazines and newspapers, but also in the international magazines ‘Nature’, ‘NewScientist’ and TIME. He published the first Dutch ‘Eureka’ translation (2003) and presented two papers on ‘Eureka’ at the international Poe conferences in Baltimore (2002) and Philadelphia (2010). His main interest in ‘Eureka’ is its history and acceptance in Europe and its influence on philosophy and science during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.