What’s so bad about spearfishing?

Spearfishing season in northern Wisconsin wrapped up this week and, as it has for the most part in the past 19 years, was a peaceful exercise of Native American treaty rights.

That wasn’t so 25 years ago when Wisconsin tribes started spearfishing in earnest after a federal court ruled that they could take unlimited amounts of fish from northern state lakes. The state Ojibwa tribes had signed treaties with the United States in the 1800s that, in exchange for turning their lands over to the government, they would be able to harvest the natural resources from the area, which covers millions of acres and about a third of the state.

In 1983 a federal court ruled that the state had to allow tribes to exercise their spearfishing rights that were granted by treaties in 1837, 1842 and 1854. The Ojibwa exchanged its lands for cash payments and an agreement that they would not have to leave the state.

The fishing rights were never allowed by the state until two native fishers were arrested for spearing in 1974. The two carried copies of the treaties on them, showed the sheriff, but the sheriff ignored the paper and arrested them. The issue wound its way through the federal courts until the 1983 Voight decision.

In 1987, Federal Judge James Doyle, Sr. (father of future governor Jim Doyle) ruled the tribes have “the right to exploit virtually all the natural resources in the ceded territory” to achieve a “modest living.”

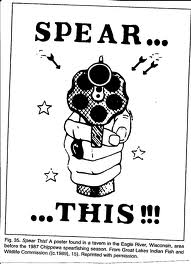

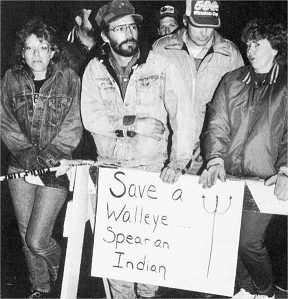

Spring spearfishers were then met with crowds of protesters shouting racial slurs, throwing bottles and sticks and in many cases having a disinterested local law enforcement doing little to prevent violence. “Spear an Indian, save a fish,” was a common bumper sticker in the northwoods for years.

I was at a tavern in Conover, just north of the fishing mecca of Eagle River during the 1980s when the owner told me, “I have a shotgun behind the bar and if any of those reds come in here, I’m pulling it out and they’re getting outta here one way or another.” The proprietor was a woman, so the racism was not gender specific.

In the early 1990s we headed to a boat landing in another tourist area looking for a place to camp, only to roll into a serious protest, where they wouldn’t let the fishers off the water after they finished their work. The sheriffs there, in Price County, said the crowd would settle down and eventually disperse. It was hours later until that was the case.

But that wasn’t the case in many boat landings across the north. Organized by two groups, Stop Treaty Abuse, and Protect Our Rights and Resources, boat landings were the scene of violence not seen since the civil rights marches of the 1960s. The American Indian Movement (AIM), which was the major player of the Wounded Knee sit-in, got involved as did many civil rights leaders around the country.

The protesters were fueled, not only by beer, but by misinformation that Indians taking some 18,000 fish a year would deplete the resource and ruin the tourism economy. (In contrast, anglers take about 300,000 fish a year from the same area.) With the state refusing to initially negotiate fish limits with the tribes, the tribes would fully exercise their rights and take the most fish they could spear from selected lakes. That also fanned the flames of racism and the state then instituted arbitrary bag limits for recreational fishers that gave the impression for most that the fish were being alarmingly depleted.

A 110-page study by state, federal and tribal agencies found that spearing does not adversely affect the numbers of the fish population available for sports anglers. It also found that about 6 percent of the fish take is by Indians. Tribes also have their own fish hatcheries and restock spearing lakes.

After federal lawsuits were filed, the courts placed injunctions against leaders of the protest group and the perpetrators and organizers of most of the violence, stating that they were violating the tribes’ civil rights. That, at least, took the violence out of the headlines and the protests died off. It also created a changed atmosphere in the north, to one of quiet acceptance, since time showed that the fish were not becoming extinct in the pristine waters of the Wisconsin northwoods.

Only about 450 tribal members spearfish each season.

Years after my foray into the Conover bar, I stopped again and was told that the bar owner had actually been run out of town since the locals didn’t share her poignant views any longer.

The state government also came around to the realities of spearfishing as well, discontinuing efforts to buy the tribes’ rights out or to set up previously arbitrary quota limits to recreational fishers. In 1991, then-state Attorney General Jim Doyle said that the both sides should just live with the court rulings. The state Department of Natural Resources began to work with the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, which was set up in 1984 by state tribes to offer its own take on managing the resources of the north.

Tribes would say how many fish from each lake they would take and the DNR would then set bag limits for the rest of the year, usually a two- or three-daily limit of walleye was the answer. Most lakes have a five-walleye limit in the state.

But those discussions depend on who’s in the statehouse at the time. This year the DNR took a hardline approach to tribal spearing, saying it would impose a two-fish limit on all lakes in northern Wisconsin. That ignored a previous agreement the state and tribes had for the past 15 years, fueling speculation in the papers of a “major conflict” again brewing in the northwoods.

The state DNR is now headed by former state Sen. Cathy Stepp, a Republican who barely eked out a win for her seat. She served from 2002-2006. Her environmental creds aren’t respected as she was the wife of a construction contractor in the urban southeast part of the state and has long been critical of the DNR and its mission. When she was appointed it was termed akin “to putting Lindsay Lohan in charge of a rehab center.” She does have a pond on her land in Racine County.

Her initial hardline stance was tempered the weeks before the season started this spring. The two sides decided on 14 lakes that would be speared to a two-fish a day limit and the rest would be at three-fish limits.

Michigan tribes entered into a court-ordered consent decree in 2000 with the state, which uses several mathematical factors in determining their fish take on ceded lands in that state. That agreement runs through 2020.

In Minnesota, tribes there tried to negotiate with the state on their ability to spear fish. The state legislature refused to make a deal and the courts ordered that the Mille Lacs Tribe would be able to spear on certain lakes the tribe would self-regulate. Two years ago, tribal fishers went outside the agreed upon fishing area to fish with nets (also allowed by treaty) and were cited for violating the law. They asserted the tribes should be allowed to fish most lakes in northern Minnesota, per the terms of an 1855 treaty.

Since there is no settlement on that issue, it’s looking like Minnesota is headed the Wisconsin way–just 25 years later.

(Feature photo courtesy of the museum at chippepedia.org)

Doug Hissom writes a weekly environmental column for Baltimore Post-Examiner. He has covered local and state politics in Wisconsin for more than 20 years. Over the course of that time he was publisher, editor, news editor, managing editor and senior writer at the Shepherd Express weekly paper in Milwaukee. He also covered education and environmental issues extensively. He ran the UWM Post in the mid-1980s, winning a Society of Professional Journalists award as best non-daily college newspaper. An avid outdoors person he regularly takes extended paddling trips in the wilderness, preferring the hinterlands of northern Canada and Alaska. After a bet with a bunch of sailors, he paddled across Lake Michigan in a canoe.