QUARANTINED in the Year of the Rat: How a New Year’s trip to China turned into nightmare for Md. family

For the Chinese New Year in January, Howard Community College language professor William Lowe was in Wuhan and Hubei province, the center of the outbreak of the coronavirus, with his wife Xiaoli and their daughter Weiya. They wound up quarantined there and then were able to be evacuated by the U.S. embassy back to the United States. They were quarantined again at Lackland Air Force Base near San Antonio, Tex. They got back to Maryland just after midnight last Friday, Feb. 21.

Here is a slightly edited version of the powerful journal professor Lowe kept of his family’s six-week ordeal. Fortunately, none of them got sick.

By William Lowe

It’s all in the timing; to get caught up in an epidemic while traveling, a lot of things have to go wrong at precisely the wrong time.

We had come to Hubei to visit my wife’s family for Chinese New Year, flying into Shanghai Dec. 31. At around the time we were in flight, a Wuhan physician named Li Wenliang posted a warning in a WeChat group (A Chinese messaging app) for doctors about a new virus that produced SARS-like respiratory infections.

A few days after we landed, Dr. Li was forced by local police to sign a statement that his post was untrue and an instance of spreading rumors detrimental to the public. After a week visiting family and friends in Shanghai and Anhui province (Maryland’s sister state), we arrived in Wuhan on Jan. 6 and departed for Shiyan the next day.

The day we left Wuhan was the day that the mysterious illness was first identified as a novel coronavirus. Two days later, the virus claimed its first victim. At around the time we departed from Wuhan, Dr. Li was hospitalized with coronavirus and would die from the infection in less than a month.

As I write these words from quarantine in Texas in the second week of February, the death toll is over one thousand. Beyond a text message that my wife received from her sister on the day we arrived in Wuhan about a mysterious new illness, we were not aware of the peril we had entered. Even when news of the virus in Wuhan first began to circulate widely in mid-January, it seemed remote from where we were at the apartment of my wife’s parents in the Yunxian district of Shiyan.

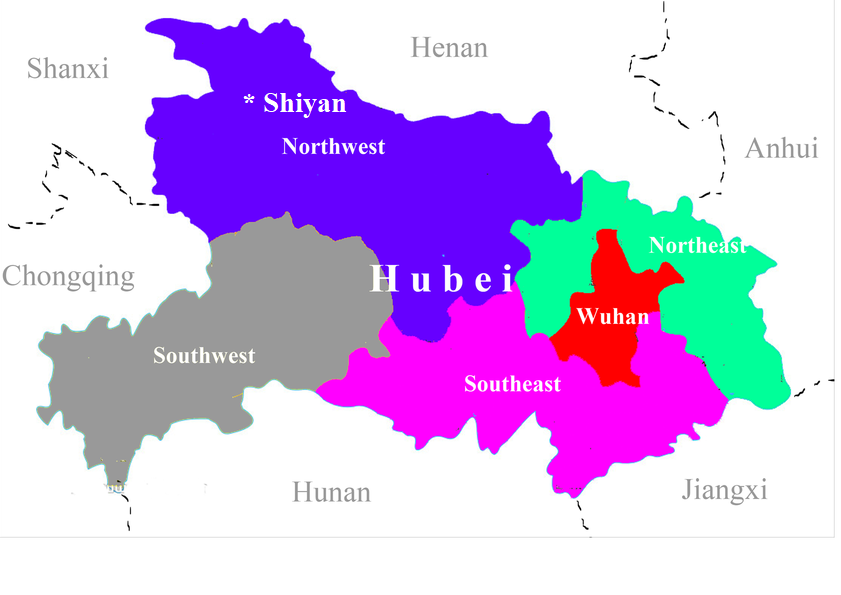

Shiyan is in the far northwest corner of Hubei Province, 275 miles from Wuhan in the far southeast. However, as we learned all too soon, what happens in Wuhan can impact not only all of Hubei but all of China and the whole world.

January 6-7, 2020: Wuhan

This trip was the third time I had visited Wuhan, though it’s not a city that I know well. My wife Xiaoli (sheow-lee) went to college and graduate school in Wuhan, and most of our time there on this visit was devoted to reunions with former classmates. We stayed with a friend and mentor of Xiaoli, a person who had a large apartment and a car.

We benefited from the friend’s hospitality in two ways while we were in Wuhan. By staying in his apartment rather than a hotel, we limited the kind of interaction with strangers that we would have had in a hotel. In the apartment, we interacted with Xiaoli’s friend and his wife and one other couple, which greatly reduced our chances of being infected. Maybe, more importantly, we didn’t use any public transportation while we were in Wuhan. Rather than being packed into buses and subway cars with people infected with the coronavirus, we rode in a private car with one other person.

When you live or travel in China, you start to get a sense of how crowded being in a country of more than a billion people feels like. China has 65 cities with more than a million people, and by counts that include municipality boundaries rather than metropolitan populations, that figure goes up to more than 100. By the municipality count, even Shiyan has more than three million, though, from the room where I wrote early drafts of this narrative in the Yunxian district of Shiyan, I could see vegetables growing in small plots of land and mountains with almost nothing but trees on them. Hardly a picture of urban life.

When I first visited northern Hubei 11 years ago, it was very rural, but that’s changing now, however gradually.

By any measure, Wuhan is a big city. It’s a sprawling urban place with a population of 11 million. The mayor of Wuhan estimated that 5 million people left the city before the quarantine went into effect on Jan. 23. Now all of China and the rest of the world trembles, waiting to see just how far and wide those departed seeds will carry the virus as they scatter in the wind. (The article continues below the maps.)

Illiterate in China

What is it like to be unable to read Chinese during a time of crisis? Certainly, that question was among the sources of anxiety for me over the last few weeks of my time in Hubei. There was nothing available online in English about how the epidemic was affecting local conditions in Shiyan.

I had been reading in English online for days about the quarantine in Wuhan and the travel restrictions imposed on cities in the immediate vicinity of Wuhan, but when the restrictions were imposed across Hubei Province, including Shiyan in the far northwest, it came as a shock to me.

I’m not sure how much warning a person literate in Chinese would have had, but it felt like my illiteracy was part of what kept me in the dark.

It is also humbling and disempowering to be in a place where I fall so far short of self-sufficiency. In the U.S., I feel like I can generally handle most problems that arise by myself, and if I can’t, I know who to ask and can ask by myself.

While I can recognize some Chinese characters on things like buses and announcements on digital highway signs, I rarely know enough of the characters to comprehend the meaning. It would be like trying to read a passage in English when you only know 5% of the words. The five percent of the words you know would be of so little use that knowing so little is indistinguishable from knowing nothing at all.

While my oral Chinese is much better than my ability to read Chinese, I fall short in this respect as well. From my experience living and teaching in China for two years, I acquired what I think of as functional or get-around Chinese.

I never spent much time studying Chinese in formal contexts but instead just learned what I needed to know to live and travel in China. I can handle simple interactions and tasks such as asking for directions, negotiating prices, purchasing tickets, making introductions, ordering food in a restaurant, etc.

It’s a kind of scripted Chinese, and so long as both parties stick to the script, I’m fine. But when the other party goes off script, I get lost rather quickly.

How to converse about an epidemic was not among the scripts I acquired. It was my idea to call around to local government offices to see if there were any that could help us, but I couldn’t have made those calls myself. There are few people who work in government offices in Shiyan who can speak more than rudimentary English.

Xiaoli had to make the calls that connected us with the Foreign Affairs Office in Shiyan that coordinated our trip to the airport in Wuhan on the day we traveled there for our evacuation flight. Had not Xiaoli or some other bilingual native speaker been available to help, we would not have been able to get out. Left to his own devices, a person without good Chinese would be stuck.

Our five-year-old daughter Weiya can read and write more characters than I can, and she also has a higher level of oral proficiency. There were times during this trip when there were miscommunications between Xiaoli’s family and me, and Weiya was able to clear up the confusion by serving as a translator. That’s part of the humbling effect of my limited Chinese. It’s rare that one gets the chance to be dependent on his five-year-old daughter.

There were occasions when my limited Chinese was a source for worry that heightened my sense of confinement and powerlessness. In the last week of our stay, the Shiyan government began to tighten the terms of the municipal quarantine.

February 1-6: The streets were empty

The last time I walked to the park was a few days before we departed. The park had winding paths and an observation tower with a great view of the Han River.

The day was sunny and clear, with a panoramic view of the mountains that surround Yunxian, though I couldn’t see them at all most days due to a dreary fog that never lifted.

On the three-mile walk to the park and back, I saw almost no one. There were a few people walking around and virtually no vehicles other than ambulances in sight. I probably could have taken a nap in the middle of the road and awakened unscathed.

Being in Hubei on those days felt post-apocalyptic, like being among the last humans on earth. It was eerie and also irrational. Microbes aren’t cartoon superheroes that can do triple backflips and shoot straight up your nose from a mile away.

In the open air, someone would have to cough or sneeze right in your face to infect you. I didn’t come within 20 feet of anyone on my walks and would rate the risk of venturing out at zero, but still, my excursions made everyone in my wife’s family nervous, even as they helped me keep my own sanity, though I lacked the words to explain this to them.

There were only two other people in the park on the day of my last visit, and while I was there, a car came by with a siren and a message booming from a megaphone. I couldn’t understand what the message was saying–probably “get the hell back inside now.”

On my walk back to my in-law’s apartment, I saw a few people sitting on the blanket in the grass. A police car came by, and the officer shouted at them. They gathered up their blanket and left immediately.

I began to worry that I might be confronted next, but the police car sped off, not toward me. I had the foresight to ask Xiaoli to write a note in Chinese to explain who I was and where I was staying in case some unexpected confrontation occurred, and I carried that note around in my wallet for two weeks like a pass.

Finally, I decided that it wasn’t worth testing whether that would be enough. I only walked inside the community in the last few days before we left. I didn’t want to take the risk of going out again. The way my luck had run in Hubei, it would only be fitting if I got thrown in a Chinese jail just before I might finally have the chance to get out.

Sabbatical

This is not how I imagined the Lunar New Year beginning. Nor is it how I imagined spending my sabbatical. I was only able to take this trip at this particular time because I am on sabbatical from my teaching position for the spring semester.

Who else might get to say that he spent a sabbatical under quarantine during an epidemic? With its associations with the Black Death, maybe it’s only fitting that 2020 is the Year of the Rat.

Xiaoli’s parents live in a small two-bedroom apartment. Her brother’s family lives in another apartment in the next building. Xiaoli’s sister and daughter were visiting as well. During the day, everyone tended to gather in Xiaoli’s parent’s apartment. There were seven adults and four children.

The adults (excluding me) talked in a high volume in the local dialect constantly in voices that scraped my brain like soiled fingernails. They could have been talking about the weather, but to my ears, it sounded like an argument that never ended. And then there were the children, who made all the noises that children make: whining, shouting, screaming. There was no private space in the apartment, and in the waning days, no place to escape to all.

I had made it bearable before the quarantine by taking interesting trips every week for a few days to places like Wudong Mountain for a solo hike and a weekend in Xiangyang with my wife, but even local travel was not possible in the last two weeks of our stay.

We had been going to a gym that had a pool where I had kept up my swimming regimen and also provided a comfortable workspace, but like all public spaces, it closed amid the virus fears. I could take walks around the community, but it was not a place to lift one’s spirits.

The neighborhood

The area has 10 high-rise apartment buildings that are 90% vacant. All over China, there are ghost cities like this. The local government tried to stimulate the economy and boost employment by investing in big construction projects, but the price of real estate is out of the reach of most local residents.

Xiaoli’s parents got their apartment as compensation for tearing down their old farmhouse to build a road. On the ground floor, the buildings have commercial space–dozens and dozens of shops, universally empty. I wondered how long it would take me to find something where I could buy a snack within walking distance. I walked about a mile and found a small grocery store and bought a bag of potato chips for Weiya. That was the highlight of my day.

Since we left, things have gotten much worse in the community. Someone in my brother-in-law’s building was diagnosed with coronavirus two days after we left. Now that building is in total lockdown. No resident of the building will be permitted to leave his or her apartment until further notice, and food will be delivered periodically door to door. More severe restrictions have also been imposed on the whole community, with only one person per household being permitted to venture out for food and other supplies every four days. I can see from afar that what felt suffocating for me was relative freedom.

Jan. 31-Feb. 6: A chance to leave

We had planned to return to the U.S. on Jan. 29, but the travel restrictions imposed across Hubei on Jan. 25 made it impossible for us to reach Shanghai for our flight. Just as I began to lose hope that we would have any chance to leave for months, I read the following message on the U.S. Embassy site on Jan. 31:

“The Department of State will be staging additional evacuation flights with capacity for private U.S. citizens on a reimbursable basis, leaving Wuhan Tianhe International Airport on or about February 3, 2020. Interested U.S. citizens in possession of valid passports should contact CoronaVirusEmergency [email protected]. There is no need to call to confirm receipt of your email; you will be contacted.”

I immediately replied with the information the embassy requested along with some details about our location. More than 30 hours passed before I received more than an automated reply. I wasn’t even sure it would be possible to get anywhere close to the Wuhan airport 275 miles away.

I knew that we would need to secure a pass to get through blocked roads and worried that there would be a total block on the roads into Wuhan. I imagined us having to travel some distance on foot with our luggage to get there.

I read online about an American student who had secured a seat on the first plane but had to walk about 30 miles from South Wuhan and missed the flight. And the announcement about the evacuation flight seemed to exclude my wife, who holds a green-card as a permanent U.S. resident, but is not a citizen.

About 32 hours after I first contacted the embassy in far-off Beijing to try to secure seats on one of the evacuation flights, I finally received an email confirming that I had secured a seat or seats on a flight. But it noted that the flights had been delayed until some unspecified date and time. The message was exasperatingly vague.

It didn’t even include the names of the travelers whose seats had been confirmed but merely used the pronoun “you,” which could be singular or plural in varying degrees. Among the many things, the embassy was unclear about was whether the flights were only for U.S. citizens. One person at the embassy indicated by phone that Xiaoli might be able to go with her green card, but the announcement on the embassy web page suggested the opposite. Our daughter was born in the U.S. and thus automatically a citizen.

Soon after I received the message from the embassy, Xiaoli learned that the Office of Foreign Affairs in Shiyan would go beyond anything I imagined to help us. For about $135 U.S.D, they would provide a car, a driver, and passes that could get us from Yunxian to the airport in Wuhan. For the first time since the travel restrictions were imposed, I began to believe that we might actually be able to get out.

Just as everything started to come together, it fell apart. As we were on the road to Wuhan on Feb. 4, the Office of Foreign Affairs informed us by phone that a mistake had been made, and Xiaoli wasn’t on the flight list for that day. We immediately called the embassy and were assured that instead, we could get three seats together on an evacuation flight on Thursday. Thus, an hour into our trip to the evacuation plane, we turned around and headed back to Yunxian to wait two more days.

It’s hard to know exactly what the source of the problem was. I’m sure for the embassy staff coordinating the evacuation flights was a monumental undertaking, and monumental undertakings might inevitably lead to myriad mistakes.

In the WeChat group set up by the embassy to handle problems with transportation to the airport, people wrote about a range of difficulties they encountered. One person was told at a roadblock that she was on the flight list but her driver and the car were not registered properly; she could go through on foot if she liked, but the driver and car could not. Others who had received the same seat confirmation email that I did arrived at the airport only to discover that their names were not on the flight list after all. One man found that he was on the list but his daughter was not.

The last two days in Yuxian we waited and hoped and fretted about all the things that might yet go wrong.

Feb. 6: Escape to the Wuhan airport

The trip back to the U.S. was a unique and harrowing experience that I hope never to come close to repeating again.

We left Yunxian a little after 2 p.m. on Feb. 6 in a car provided by the Shiyan Office of Foreign Affairs, which also provided drivers and passes to get through roadblocks. Without the assistance of this office, we never would have made it to Wuhan for the evacuation flight and would have been stuck in Hubei until May as the earliest.

It snowed overnight in Yunxian on Feb. 6, though there was little snow on the ground near the community of Xiaoli’s parents. However, as we headed south toward Wudong mountain, the ground and the trees were thick with snow, and snow had accumulated on the shoulder of the highway, as well—as if we needed anything else to worry about.

Finally, as we made it out of the mountains, the snow disappeared, and it was a smooth ride from there to Wuhan. The drive took only a little more than four hours, and we only had to pass through one significant roadblock—the one that let us get on the G70 freeway that ran from near Yunxian straight to Wuhan. We made it despite the fact that the car carrying us was a Chinese model called the Trumpchi—the Trump car. It’s the first time that something named Trump carried me anywhere that I wanted to go.

The embassy requested that everyone report to the airport by 9 p.m. We reached the meeting point inside the airport before 7:30 p.m., and then the waiting began.

Everyone in the airport was decked out in masks and various forms of protective gear and clothing. One person wore something on her face so elaborate that it looked like she was scuba diving indoors.

It was around 10 p.m. before anything began to get organized. There were forms to fill out, health screenings to complete, and customs to pass through; it was nearly 3 a.m. before we finally reached the gate. Sometime after 5 a.m., we boarded the plane, but it was around 7:30 a.m. by the time we took off—a full 12 hours after we arrived at the airport.

Feb. 7: A surreal flight back the U.S.

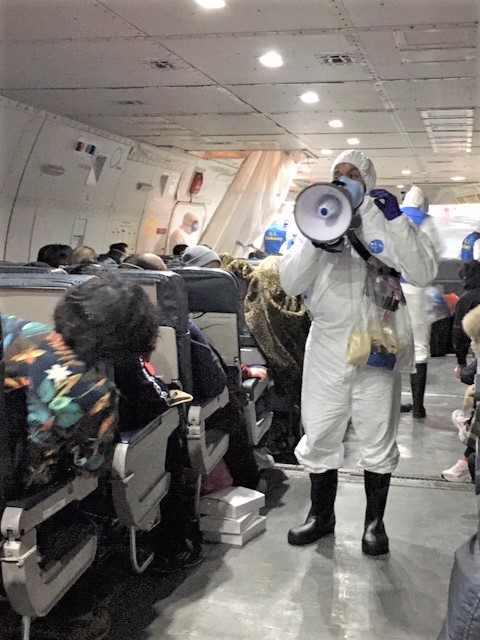

The flight back to the U.S. was a surreal experience. The plane was a cargo craft with a mismatch of 400 passenger seats installed in the expansive interior. On the back of my seat, I saw something written in Russian, and a sign on the wall was in Korean.

Within the cavernous cabin, I noticed only two small windows. Instead of flight attendants, the plane was staffed with embassy personnel and doctors in biohazard suits.

One of the embassy staff members must have been close to 7 feet tall, and as I watched him walk up and down the aisle in his oversized boots, it felt like the march of a waking nightmare.

There was no intercom system on the plane. Embassy staff made announcements on megaphones that weren’t nearly loud enough for everyone on the plane to hear. The restrooms were a row of porta johns rooted somehow to the cargo plane floor. The passenger list included 380 names, but in reality, only about 250 people boarded the plane, including many families with children. The family across the aisle from us had two sons under six and a one-month-old infant.

No matter the challenges, everyone on board must have felt immense relief when the plane took off and an even greater relief when it touched down in California.

I know from posts in the WeChat group that some people were unable to get through roadblocks.

One person’s car broke down on the way to the airport. Some people with young children decided that their families weren’t up for the trip. Some people had paperwork problems at the airport and were unable to reach the gate.

Many of those who didn’t make this flight sent out inquiries to see if there would be any subsequent flights. As far as I know, the answer to that question was “no.” Missing this flight meant being stuck in Hubei for months during an epidemic. I feel for those folks and feel very fortunate that my family and I were able to get out.

Gorging on snacks

When we boarded the flight, there were boxed lunches on each seat. Given that this was the first meal we’d eaten in about 17 hours, I ate it thankfully while thinking that the ham sandwich with coleslaw was the worst I’d ever had in my life.

For the rest of the flight, Weiya and I went on a bit of a snack bender to make up for the scarcity of treats during our confinement in Hubei. There were boxes of chips, cookies, brownies, Dove candy bars, sodas, etc., and we ate and drank so much that on the second leg of our flight, we both felt a bit sick to our stomachs.

I imagined having to explain to the doctors on board that I wasn’t rushing to the bathroom because of coronavirus but instead because I had merely overdosed on sugar.

February 7: Touching Down

We landed at Travis Air Force Base in Fairview, California, at around 4 a.m. We disembarked from the plane and then went through a health screening and a sort of customs lite. I later read online that four people on our flight were hospitalized in California after showing coronavirus symptoms. This left me to wonder where those four people were seated in relation to us and just how risky this flight might prove to be.

After waiting for twelve hours and flying for twelve hours, I was so ready to be sent to a room at Travis and get some sleep, but that was not meant to be. Our arriving flight was divided into three groups, with some staying at Travis, others going to Texas, and the remainder being sent to Omaha. The Omaha folks got the worst draw, having to stop in Texas before moving on yet again. Theirs was the longest flight to get to the coldest place.

February 7- 20: Confining and claustrophobic

After processing and eating lunch in an aircraft hanger, those of us designated to remain at Lackland Air Force Base near San Antonio were taken by bus to the quarantined housing on base.

The units are comfortable studios, with small kitchens and living rooms in addition to the bedroom. It’s still a rather tight place for three people, but it’s better than it might have been, and much better than I expected.

In other words, it’s a pretty comfortable prison for a quarantine that is a 14-day sentence by federal mandate for the misfortune of being in Hubei in January 2020. It has only been a few days, but already it feels confining and claustrophobic.

A fence has been installed around the facility and is patrolled at intervals by U.S. Marshals. At night, temporary generators churn to power floodlights mounted on poles that keep the entire span of the fence illuminated.

To keep cabin fever if not the coronavirus at bay, I’ve taken dozens of walks around the periphery of the enclosed area and doing so always makes me feel like a caged animal.

I can see the marshals watching me, measuring my steps from the other side of the fence, saying without words, “don’t even think about it, buddy.”

We don’t have a lot of interaction with our fellow inmates; social interaction is discouraged for obvious reasons. A catering service brings bagged meals three times a day and lays them out for pick up on long tables set up under a tent. People come and pick up the bags and return to their rooms to eat. There are 93 people here, some traveling alone and many in families. I’ve found myself wondering if in some ways this would be much easier to bear if I were alone.

I could read and write in solitude, with no need to worry about daily details such as cooking and cleaning. The latter is taken care of every day by a cleaning crew in hazmat suits—another surrealistic detail of life here. It’s one thing to have someone take your temperature twice a day in one of those suits; it’s quite another to have a hazmat housekeeper vacuum your floor and scrub your toilet.

If I were here alone, it could be a writer’s retreat at the point of the bayonet, a boot camp for prospective authors. How could one not be productive when armed marshals are lurking about, making sure you do your part?

However, that is not the reality for me, and I’m in a tight space with my spouse and five-year-old daughter. I spend most of my time each day trying to keep Weiya amused. She’s such an easy-going child that it’s not challenging in one respect, but it takes time, and in this sense, amusing a child in a studio for two weeks with no contact with other children in the facility is anything but easy.

The staff here and on the plane and every stop along the way have been universally friendly and supportive, but it is hard to be here when I just want to be home. I understand the reasons for the quarantine and fully support the idea intellectually, though emotionally, I feel suffocated and must admit that as I walked along the fence it crossed my mind more than a few times to look for the best place to leap over and make a run for it.

Feb. 20: Released and Home at Last

At 9 a.m. on Feb. 20, we and the other 90 people quarantined at Lackland were officially released. We boarded three buses, one of which dropped off my family and me at the San Antonio airport. After an afternoon of waiting at the airport, we flew home that evening and disembarked a little after midnight at BWI. A friend picked us up at the airport, and within an hour, we were sleeping in our own beds for the first time in nearly two months. With our CDC quarantine release forms in hand, life can return to normal now.

We know that we can count ourselves among the fortunate ones. For the 60 million inhabitants of Hubei and the Americans in Hubei who didn’t make it out on one of the evacuation flights, months of anxiety and entrapment loom ahead. As the end of February approaches, all of my wife’s family members are under lockdown in their apartments in Yunxian. That very easily could have been our fate as well had our luck not turned toward the auspicious in early February.

For us at least, the Year of the Rat might not be so bad after all. For those still in Hubei, I fear that things will get far worse before they get better.

MarylandReporter.com is a daily news website produced by journalists committed to making state government as open, transparent, accountable and responsive as possible – in deed, not just in promise. We believe the people who pay for this government are entitled to have their money spent in an efficient and effective way, and that they are entitled to keep as much of their hard-earned dollars as they possibly can.