Missing the Point – The Insidious Influence of Political Money That is Contributing to the Demise of the Great City of Baltimore

We all know that political contributions, the large dollar kind, influence who we elect and what they do after they’re elected.

“So, what’s wrong with that? Campaigns are, after all, expensive.”

What’s wrong is that the needs of the electorate may not be consistent with the objectives of those “special interests” to whom the elected official – the Mayor of Baltimore, for example – is beholden.

One day, the phone rings. We’re talking hypothetically of course. It’s not the Mayor’s official office number, but his cell phone. The caller is one of his principal backers who has contributed to the Mayor’s various campaigns and encouraged the contributions of others with whom this particular caller has special relationships. Without the campaign contributions this caller has bundled, the Mayor – who is not the most qualified person to hold his position, but is compliant – would be relegated to doing something substantially more mundane for a living. Compliance in the service of campaign contributions is seldom something the most qualified candidates will offer in exchange for financial support.

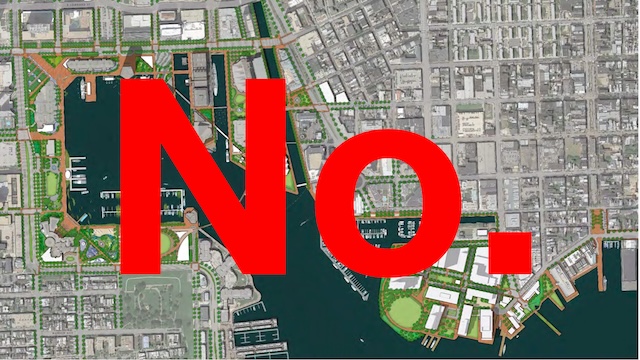

The Mayor answers the phone. There’s a brief exchange of pleasantries and then the caller talks to him about a particular project. Could be a new building here or there but, in this case, it’s about the economic and political advantages of a long overdue renovation of the Inner Harbor. “This could be the project,” so the Mayor is told, “that assures your re-election.” It’s a massive, high-profile project that reeks of leadership demonstrating a vision that will play well – not around the kitchen tables of the two-thirds of the city struggling every day to get by, but in the offices and board rooms of large dollar contributors whose businesses will benefit from the initiative.

And so it goes. Nothing new to write home to mom about. Those who matter will be pleased. Everybody else will be too worried about putting food on that kitchen table to care or to ask whether there might be something better to do with all that public money that’s going to be invested downtown.

“It’s business as usual,” you say to yourself and I agree. But as it turns out, we’ve both been missing the point.

The thing is, there are two kinds of economic development. “Local project development,” referring to real estate projects by local “developers,” is almost entirely about building something. A strip center or maybe a shopping or entertainment district. One or more office, apartment, or mixed-use buildings. A downtown casino or driving range/bar and much larger, multipurpose projects like Port Covington – because no one knows beneficial city development like a sportswear manufacturer – and the Inner Harbor project is now on the table.

The other kind of development is what I’ll call, for the sake of discussion, “urban industrial development.” Urban industrial development is not about building anything per se. It’s about high-volume job creation, the nature of which changes the financial and social topography of a city’s overall economy and certain neighborhoods in particular. Jobs, in a demand-driven free market economy, are the basis for the development and growth that the city of Baltimore so desperately needs to stop and reverse its continuing decline.

“Local project development” is a supply-side concept of sorts. A “supply-side” initiative assumes that the income generated by the project will justify its undertaking.

The developer does its best to anticipate demand for the project’s products and services. There is some hope that the employees of the project will, in rare cases, actually be consumers of whatever the project produces, but that seldom happens to any significant extent. The argument the local government makes is that development here – downtown for example – will somehow, like an infectious rash, encourage additional development nearby and elsewhere, precipitating a widespread beneficial impact for the city at large. But don’t count on it. If the various local government-supported projects over the past several decades had had this type of multiplier effect, the city of Baltimore would be on the rise rather than still losing population to the suburbs and beyond.

The problem is that our national, state, and local economies are demand-driven. Supply-side projects do not work except to benefit their developers and even that doesn’t always happen.

By comparison, “urban industrial development” – meaning, in this case, the placement of new generation “factories,” broadly defined, in the heart of those Baltimore neighborhoods having the greatest need – is a demand-side concept. Give the un- and under-employed better jobs. Jobs create demand by how employed workers spend their household income. Increase household income in the troubled segments of the city, and consumer demand will call forth all and precisely the right mix of the goods and services the community needs. Organically.

“So, why doesn’t local government – Mayor Scott, for example – do large-scale urban industrial development? Why is it always about local project development?”

Because… Because employers that could come to Baltimore from outside the city don’t make contributions to his campaigns.

The irony is that the Mayor – the current one and his predecessors – haven’t needed special interest support to get elected and stay in office. Think about it. All they’ve needed to do is offer voters this simple option…

Given a choice between some shiny new construction downtown and bringing one or more employers to your segment of the city, each of them giving 500 to 1000 local residents on-the-job training for long-term, higher-paying jobs, which option would you pick?

For which of the two candidates for Mayor would you vote? The candidate who effectively works for local developers or the other candidate who can make urban industrial development happen, giving you a better job with career potential that puts more money in your pocket?

One last point… For those of you who are opposed to the spending of $900+ million on the remodeling of the Inner Harbor, your instincts are right. What you’re missing is the need to offer voters the local industrial initiative that will not only be less expensive, but will begin the all-inclusive reversal of the city’s fortunes.

Les Cohen is a long-term Marylander, having grown up in Annapolis. Professionally, he writes and edits materials for business and political clients from his base of operations in Columbia, Maryland. He has a Ph.D. in Urban and Regional Economics. Leave a comment or feel free to send him an email to [email protected].