Media in the New Town: Communications part of building community; the Flier and the rest: Part 4

This is the fourth part in a series of 12 monthly essays over the next year leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration next June. It ran first in The Business Monthly, circulating in Howard and Anne Arundel counties, and after that, is being published here on MarylandReporter.com and by our partner website, Baltimore Post-Examiner. The copyright is maintained by the author and may not be republished in any form without his express written consent. Comments and corrections are welcome at the bottom, with links to all the published parts.© Len Lazarick 2016

By Len Lazarick

Tom Graham’s decision to move from The Howard County Times to the Columbia Flier was a bit puzzling to me as I visited him and the new planned community for the first time in early 1973.

After 14 months, Tom was leaving the well-established Times that looked like a traditional newspaper for the magazine-sized Columbia startup that looked liked it came out of a typewriter — because it did.

It turned out to be a smart decision that gave Tom a quarter-century of employment, opportunity and influence. He was attracted by the enthusiasm of the new editor, Jean Moon. Jean says she recognized that Tom was better at reporting on zoning than she was, and she also offered a small raise.

“Despite that, I didn’t say yes until I had a face-to-face with Zeke Orlinsky, the publisher,” Tom said. Tom’s future wife, Mary Kay Sigaty, “was working as a bank teller at the time, and she had warned me that the Flier’s checks sometimes bounced. When I asked him about this, Zeke said that would never be a problem with my paycheck, and it wasn’t.”

Maureen Kelley and I moved to Columbia a few months later, in June 1973. Maureen, newly graduated from nursing school at Boston College, where all four of us had met, got a job as a visiting nurse on her first interview. I got a job with another newspaper in town, Columbia Life, which was supposedly “recapitalizing.”

Columbia Life survived for another issue or two and then died without a trace. I sued the publisher for pay. All I got was an office desk and chair.

Other newspapers have come and gone — Columbia Villager, the News Columbian (an edition of the conservative Central Maryland News), The Columbia Times (an edition of The Howard County Times), and a bit later, the Columbia Forum. In the following decades, dailies would enter the local market with the Howard Sun and the Post’s Howard Weekly. There were other publications along the way, The Business Monthly among them.

But the paper that would become the dominant news source for Columbia’s first quarter-century was that puny little free “shopper” that started on a dining room table.

Planning for Communications

Communications is one of the thinner volumes in the many Green Books that document the meticulous planning and proposals for all aspects of Columbia life.

“The whole subject of communications in the planning of Columbia can only be described as a mystical religious icon which everybody revered with poignant regularity,” wrote Wallace Hamilton, Rouse’s director of institutional planning. “‘We’ve got to think about communications,’ people would say. But nobody ever really did anything about it, except write long reports for longer conferences and got more and more people into the act to share the general confusion.”

“We got intrigued with technology for technology’s sake and lost track of function,” Hamilton observed.

Although their focus was on technology, the goal of the planners remained the same as for the village centers and neighborhood gathering places — encouraging community life and spirit. The early planners reached out to the companies that were developing futuristic technologies that would become the driving forces of American communications in the final decades of the 20th century — cable TV and then the Internet. But the planners were 10, 20, even 30 years early as they contemplated interactive TV loops and other forms of electronic two-way communications.

For those under 40 and those who have forgotten, it’s worth refreshing what communications was like in the 1960s.

There were telephones, an invention of the late 19th century, but they were all what we now call “landlines,” connected by copper wires, owned and operated by a single local monopoly we called “the telephone company.”

There were urban TV stations, most of them part of the three major networks, broadcast over the airwaves to antennas. And radio, the early 20th century invention, was available almost everywhere.

All these systems were regulated by the government at the federal or state level, with a complicated set of licensing.

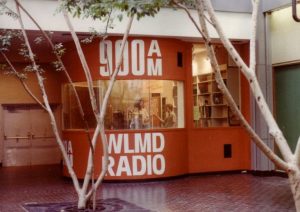

Some of the planners at the Rouse Co. wanted its own radio station, but that didn’t happen until WLMD, a Laurel station, set up a small studio in the mall in 1979. It lasted only a couple of years.

Columbia’s central location in the Baltimore-Washington corridor put it at the edge of both these big media markets. The available television channels were used up, with only slim possibilities for a UHF TV channel and an AM radio station.

In October 1970, after much back and forth, Howard Research and Development, HRD, the Rouse division managing the new town, announced that Time-Life had been granted a franchise to establish cable television in Columbia. But the cable franchises were still under local control, and Time-Life backed out when it balked at provisions in the Howard County legislation. A local group won the rights in a partnership with Warner Communications. The Howard franchise was sold to Storer Cable, which became Comcast in 1993.

Local Programming

Andy Barth moved to Columbia in August 1971, the week The Mall in Columbia opened, conveniently located between Baltimore where he worked as a reporter for WMAR TV (Channel 2) and his wife’s job in Silver Spring.

“At first it was just convenient; then we became converts” to the Columbia vision of an integrated, inclusive community, said Barth, now press secretary to Howard County Executive Allan Kittleman.

For two or three years, WMAR had a bureau located in the Exhibit Center next to Lake Kittamaqundi staffed by reporter Gene Cox.

“TV was very, very competitive then,” said Barth. He eventually spent 35 years at WMAR before retiring to run for Congress in 2006.

“Columbia was a story at that point” as the new town grew, he said. “We did a birthday story pretty much every year.”

Many Baltimore TV personalities made Columbia their home, recalled Barth: the late Al Sanders, Denise Koch, Dick Gelfman, Jeff Hager, and briefly, a young Oprah Winfrey, among others.

Throughout the years, Howard County and Columbia have been part of a tug of war for eyeballs between rival TV stations for this lucrative, high-income market.

There were many TV stories about the progressive ideas embodied in the Columbia concept, such as interfaith religious centers, but “at some point it stopped being new,” said Barth.

Yet, for all that, these were stories done for a wider regional audience.

In its first 30 years, the Columbia community relied on the oldest of the mass media, newspapers, and for several decades that medium was the Columbia Flier, from its start delivered free to all the households in town.

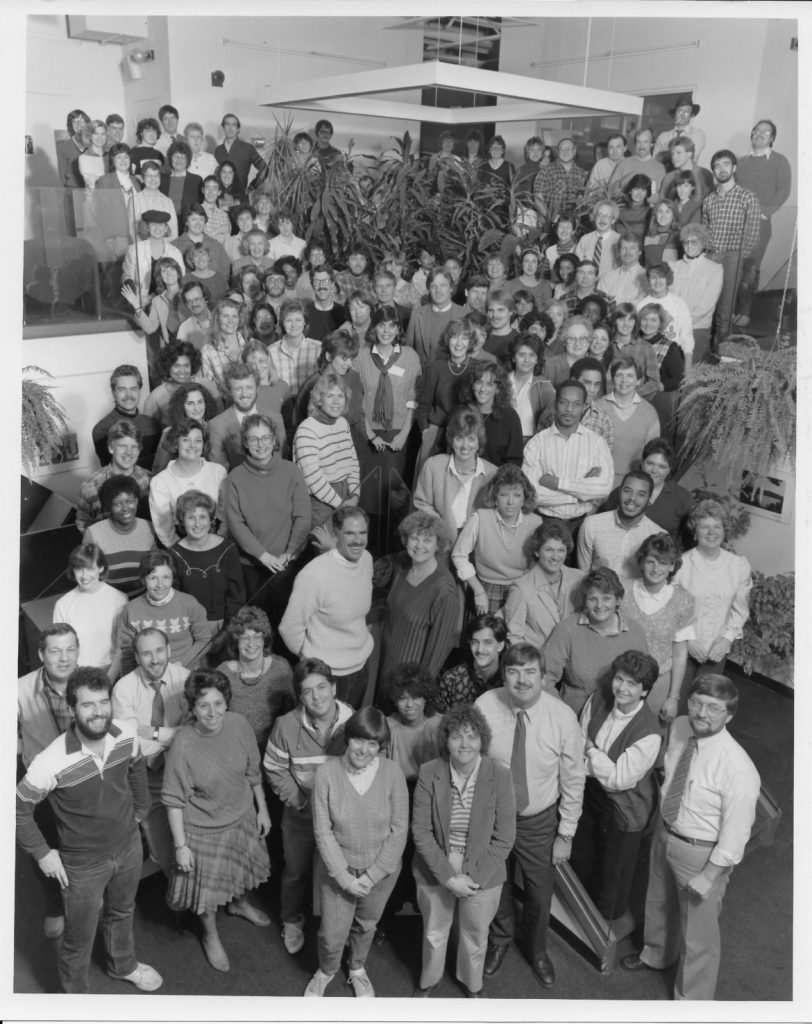

Patuxent Publishing staff, including Columbia Flier, sometime in the 1980s in the foyer of the Flier building. In the lower center are Publisher Zeke Orlinsky and General Manager Jean Moon. Editor Tom Graham is at the very bottom right; Len Lazarick is second person to his left. Photographer unknown.

The Flier

Two years after Columbia Life folded and two non-journalism jobs later, a position finally opened at the Columbia Flier, where I had done some freelance writing. I had already helped the Flier move from its small flexi size into the tabloid it became in 1974, growing to 64 pages. After I became associate editor in 1975, I covered education, business and politics. In 1976, I wrote the cover story for its first 100-page issue, a piece titled “Banned Books” on efforts to ban some books from school libraries.

We now know that we were all working in the heyday of the newspaper industry — not just in Columbia or Maryland, but in the United States. Advertising revenues were bulging, profits were ballooning, staffing soared at every publication.

There were people who loved the Flier; there were people who hated the Flier, particularly the liberal bent of its publisher Zeke Orlinsky and his weekly “Publisher’s Note.” But love it or hate it, people read it. At one point, a survey found that 92% of Columbians read the paper that landed free every Thursday on their doorsteps and driveways.

This was not your traditional newspaper produced by traditional newspaper people. Its models were magazines and the alternative city papers that grew out of the ’60s counterculture. Its editors didn’t just read The Washington Post and The New York Times, but The New Yorker and The Village Voice. It was in sharp contrast to its stodgy competitors, like the Sun.

The Flier’s sketchy origins in 1969 certainly gave no hint of the powerhouse it would become.

“I got pissed at something in the Howard County Times,” recalled Orlinsky in a recent interview from his home in Westport, Conn. “I didn’t have a vision.”

The first issue of the Flier was indeed a flyer — eight pages of legal paper folded with a Merriweather Post Pavilion ad on the front, ads for cars and tires, and a calendar of events. This first issue on Columbia’s June birthday in 1969 was reprinted several times over the years as a reminder of how far the newspaper had come.

When Jean Moon joined the fledgling operation as a writer two years later, free circulation had grown to 9,000, and there was real news in the Flier, but they were still cutting and pasting the typewritten copy on a dining room table.

At the time, Orlinsky wrote: “To reflect the growth of a new city like Columbia is to meet new challenges. It calls on a publisher to throw away the old and tired concept of journalism. Journalism is more than just information and news. Journalism should excite and guide a community.”

That statement was still being pointed to 20 years later in a history of the paper given to new staff members of a much larger enterprise.

Moon, who had come to Columbia with her husband Bob for his job as an architect at the Rouse Co., was totally on board with the concept of community journalism — “that we weren’t dailies” and the mission was to “play a role in the community,” she recalled recently.

By 1973, Moon was editor and general manager, she had hired Graham, and the staff had grown several times. By the time I joined the staff on July 31, 1975, it was operating out of a building on Route 108. It moved again to Wilde Lake Village Center, and in spring of 1978, we moved into the Flier building on Little Patuxent Parkway, an unusual building designed by Bob Moon, standing out amid the town’s bland architecture, with its white metal sides and sloping fronts of glass.

There were no crusty old editors looking over our shoulders, telling us “we don’t do that here.” Jean and Zeke — and we often talked about them that way in this family-like operation — were still in their 30s; Tom and I were in our 20s, and the staff was of similar age. While Tom and I did take photos, we eventually brought on a staff of talented photographers who made that a hallmark of the paper in future years.

The Flier was more than just a writers’ paper. What’s striking going through boxes of old clips I dragged out for this series was how closely we covered this new community — the opening of restaurants, the closing of stores, the community dustups, the arguments over tot lots and door colors, the nitty-gritty of everyday life. While there were wonderful photo spreads and long features, there was also column after column of “notices” about routine events and meetings.

Because of Jean Moon’s proclivities, there was massive coverage of the performing arts, not just in Columbia (Merriweather Post Pavilion was going strong as a venue for big acts), but in Washington and Baltimore too.

There was local sports galore including the long-time weekly column by Stan Ber called “Bits and Pieces,” a column that predated my arrival and survived long after I left 21 years later. Stan, like many of the other writers, was community bred. His day job was at the National Security Agency where he did what can never be disclosed and where they answered the phones cryptically with the last four digits of the extension you called.

Most of us lived in Columbia. We were part of the community, and the community was part of the paper. Page three had the signed “Publisher’s Note” — none of this unsigned editorial page stuff of the old school — and then there were the letters, so many letters from Columbians, often complaining about Zeke’s emotional diatribes or other coverage that pushed the envelope, like the time we put the full-page image of a mammogram on the cover to illustrate a story on breast cancer.

The Flier was the way the community talked to itself, understood itself, remembered itself.

The advertising flowed in — all the newspaper staples — cars, groceries, real estate, classifieds. “The smartest thing was not selling ads by the inch,” as dailies did, producing those odd-shaped page wells, Orlinsky said. The Flier sold eighth-, quarter- and half-pages that made design easier and more attractive.

More advertising meant more money, more pages, more stories to fill them, more staff to write and illustrate them, and more listings — and made it a more attractive target for acquisition.

The Sale of the Flier

The night of Nov. 7, 1978, a major gubernatorial election, I was covering the returns in the Kiwanis Hall in Ellicott City, and a reporter from the Howard County Times asked me my reaction to the sale of the Columbia Flier.

I was floored. Sale, what sale? Jean had tried to have me tracked down that night — this was decades before cell phones — so I would not learn of the deal from our local competitors who had gotten wind of it.

Who were these guys at Whitney Communications? Turns out these guys — and yes, they were all guys — were some of the classiest in the business. The chairman, Walter Thayer, had been the publisher of the vaunted New York Herald Tribune, and the president was John Prescott, former president of The Washington Post Co. Millionaire John Hay Whitney had founded the company.

It was one of the best things that ever happened to us. Jean and Zeke were left fully in charge. A year later we bought The Howard County Times and other papers in the chain. I got to spend full-time in Annapolis during the 90-day sessions as political editor. When John Hay Whitney died in 1982, the partners created a working fellowship that sent Tom Graham and then me to Paris for a year at the International Herald Tribune, where Whitney had been the managing partner of a three-way ownership split with the Post and The New York Times.

We won award after award, both state and national, for writing in many categories, photography and design.

The Flier kept chugging along, and in 1988, our newspaper group, now called Patuxent Publishing, bought Times Publishing in Towson and its five newspapers, including the Towson Times and The Jeffersonian. I became managing editor of seven Baltimore County papers.

“We never recovered from that purchase,” said Jean Moon in a recent conversation. In hindsight, she said, “We overpaid for those newspapers” and struggled to make them generate enough return on that investment.

Management began making cuts in the 1990s as Maryland experienced a harsher recession than the rest of the country. In 1995, a Whitney Communications partner and Zeke told Jean Moon she needed to go, and in June 1997, six months after I left, Patuxent and the Flier were sold to the Baltimore Sun and its new owner, Times-Mirror.

“I really don’t think [the sale] will change anything” about the newspapers, Orlinsky told me for a story I wrote about the sale in The Business Monthly. “It’s not in their interest to screw it up.”

Orlinsky stayed on as a consultant for a year, having twice sold the same paper at a handsome profit. He was wrong about nothing changing.

Orlinsky says now he had seen some of the handwriting on the wall a few years before as the Internet began to spread. “I didn’t understand it” but “I knew that it was only a period of time [before] newspapers would lose those categories” of classifieds — employment ads, real estate and cars.

What began as small dips in revenue in the 1990s became a steady downhill slide and then, in 2008, as the Great Recession hit, newspaper revenues fell off the cliff. As advertising evaporated, pages and coverage were cut, as were the reporters and editors who produced them.

Along the way, Times-Mirror sold the Sun and the local papers to the Tribune Co., which went private and then bankrupt for years, and now has the god-awful name of tronc. Over the years it has decimated staff and closed offices, including the Flier building on Little Patuxent Parkway in 2011.

The Flier is now run by editors in the Sun’s downtown Baltimore building. What were once several independent news operations in the city and the five counties that surround it are now under one owner, the Baltimore Sun Media Group, with copy shared among all. In the Flier you can read articles you may have already read in the Sun, or the other way around.

The only locally owned and operated news outlet is The Business Monthly, where this series is running before it is published here. Started in February 1993 by Ed and Carole Pickett as the Columbia Business Journal, it was geared to just a sliver of the community. It became The Business Monthly nine months later after Orlinsky registered all the other likely publication names, and the Picketts decided not to fight him.

Carole grew up as Carole Ashbaugh in western Howard County, married Ed and had three children at a very young age. By the time they returned to Howard County, they had run several newspapers in Vermont, and radio stations as well.

Carole, now Carole Ross, says it was her idea to start a business paper here, with Ed as editor. When Ed soon after decided also to launch the Columbia Daily Tribune, that was the last straw for Carole after many, many straws with her spendthrift hubby.

She called it quits on the marriage, but kept The Business Monthly, $68,000 in debts and all. But aside from Ed’s spending, “It made money from the very first issue,” she said.

From its start, one of The Business Monthly’s gems were the columns by Dennis Lane, ostensibly about his field of commercial real estate, but really wise and funny commentaries on public life. Under the moniker WordBones, he became one of the best and most provocative bloggers on local life and added a podcast with attorney Paul Skalny to his media chops until he was brutally murdered in 2013. On Oct. 19, a new road near Merriweather Post Pavilion, where Dennis worked as a teenager, will be dedicated as part of Columbia’s revitalized downtown. It will be called Dennis Lane in an amusing tribute to an amusing writer in a town full of weird street names drawn from poetry and unconnected to persons living or dead.

Carole sold The Business Monthly in 2002 to Becky Mangus and Cathy Yost. I worked with both sets of publishers from 1998 to 2006, when I became State House bureau chief of the Baltimore Examiner, which covered Howard County in its typically haphazard way, with its usually erratic free delivery, until its untimely demise in 2009.

Not the Only Game in Town

The Flier was never the only game in town. The Sun had an Ellicott City bureau for many years with Mike Clark reporting there for decades; the News-American and Evening Sun were represented too.

In the early 1980s, attempting to capture more suburban readers across the Baltimore region, the Sun set up the Howard Sun with a separate, and lower paid, staff that competed strongly with the Flier for stories and advertising. The Sun tried various configurations of separate Howard County sections for years after it bought the Flier and Howard County Times, and still has a thin section in the Sunday paper, though the content is often shared.

The Washington Post also had the Howard Weekly, part of a plan to open bureaus in all the counties it served. It leased premium space in downtown Columbia, but never filled it. It was later replaced by the Howard Extra. The Post, for which I worked part-time on the national copy desk for eight years, and Tom Graham has for 16 years, has largely abandoned local coverage under the ownership of Amazon’s Jeff Bezos.

Many Columbia residents mourn the loss of the Flier they remember from years ago, a fat, thriving community newspaper operation. Jean Moon, who created a new career for herself as a public relations consultant to some of the biggest organizations in Columbia, said, “People complain all the time” about how thin the Flier is. But she said those are people of “our generation,” meaning the over-65 crowd, bemoaning the good old days.

“I don’t feel a concern about creating community anymore,” Moon said. “People see no need for a community newspaper.”

Pat Kennedy, now 82, president of Columbia Association from 1972 to 1998, is one of those who mourns the loss of the Flier, which he saw as crucial in creating a vibrant community.

The building that housed that crucial community builder has sat empty for several years. Howard County Executive Ken Ulman wanted to turn it into a business incubator, but for the Kittleman administration, the price tag was too high. It may now be torn down and replaced with “affordable housing” as part of downtown Columbia’s revitalization.

For Kennedy, the tearing down of the Flier building stands as “a metaphor for the decline of the newspaper industry” as a whole.

Next month in Columbia at 50: Politics and Governance

Len Lazarick ([email protected]) has lived and worked in Columbia as a journalist for more than 40 years. He is currently the editor and publisher of MarylandReporter.com, a news website about state government and politics, and a political columnist for The Business Monthly.

MarylandReporter.com is a daily news website produced by journalists committed to making state government as open, transparent, accountable and responsive as possible – in deed, not just in promise. We believe the people who pay for this government are entitled to have their money spent in an efficient and effective way, and that they are entitled to keep as much of their hard-earned dollars as they possibly can.