Maryland’s Blueprint to prepare students for college and careers – and counselors lead the way

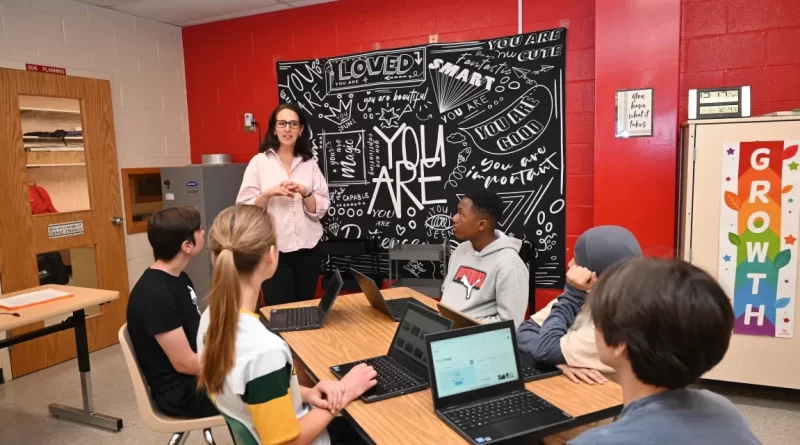

Northern High School had never had a career counselor. Not until Christian Wargo walked through its doors.

In September, Wargo became the Calvert County high school’s first career advisor as a part of the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future, a multi-billion dollar legislative plan to improve education across the state.

Now, every school district across the state is hiring career counselors like Wargo to help students navigate a pressing question: What do they want to do when they grow up?

Wargo said his help is in high demand.

“I’m in the classrooms a lot with the kids still introducing myself so they know who I am, but I’m starting to have a lot of students come to me on their own,” he said.

A new emphasis on career counseling is just part of the Blueprint’s college and career readiness “pillar,” which starts with an ambitious goal: to make sure all high school students are prepared for their next steps after high school by the end of the 10th grade.

Many students fall short of that goal now, and Rachel Hise, executive director of the Blueprint’s Accountability and Implementation Board, said that leaves educators with an important lesson.

“The bulk of kids need something different than what we’re doing for them now,” Hise said.

That “something different” is already taking shape amid the state’s education bureaucracy and at its 1,421 or so public schools. The State Department of Education is redesigning curriculums and has already revised how to measure college and career readiness. Districts are funneling more high school juniors and seniors to dual enrollment programs at local community colleges, and schools are placing a far stronger emphasis on career and technical education.

A sweeping curriculum overhaul

All Blueprint changes need to be in place by the 2031-2032 school year. While each school district is tasked with developing its implementation plan, one key to the Blueprint is a “model statewide curriculum” that’s currently under development.

“We are trying to get rid of our gaps and to really understand what we need to do to meet our kids to make sure that they leave us prepared for college, career, and life,” said Rachel Amstutz, policy director for the Accountability and Implementation Board that’s overseeing the Blueprint rollout.

While it’s not yet clear what those changes might entail, the Blueprint Implementation Plan discusses possible adjustments to math, English language arts, science, and social studies curriculums to align with local college admissions standards and research on student learning.

“You’ll hear us talk about reimagining the school day,” Amstutz said. “We don’t envision high school looking like what high school has looked like since my parents were in school.”

The Blueprint also requires a universal standard to measure college and career readiness. The state had been using Maryland Comprehensive Assessment Program scores, a state standardized test, as an indicator of success. By 10th grade, students need to meet expectations in English language arts and math to be deemed “career and college-ready.”

But the test results from the 2020-21 school year, the latest available, showed just over half of students (53.5%) met the English language arts requirements and roughly 40% passed math standards by 10th grade. Maryland high schoolers have to take the test to graduate, but aren’t required by the state to pass. However, starting this year the government and life science tests will count for 20% of a student’s course grade.

Studies commissioned by the Blueprint found that including an alternative to demonstrating college and career readiness through passing exams, such as earning a 3.0 GPA, was more inclusive than standardized tests alone and better predicted student success in college.

That being the case, the State Board of Education in January unanimously adopted a new set of college and career readiness standards last month that includes that GPA measure as an alternative to test scores.

Now it’s up to teachers, career counselors and students to try to meet those standards.

“The Blueprint is really asking us to rethink what high school looks like and really make sure that we’re preparing all of our students to go to college or enter the workforce in a way that we just haven’t done before,” said Sarah Bento, assistant principal at Northern High School in Calvert County.

College Prep: AP Classes and Dual Enrollment

The requirement to add career counselors in every school means students will have more support to think about what they want to do. For many, that still means pursuing a college degree.

On average, roughly half of Maryland high school graduates go straight to college after high school.

Northern High School sophomore Simon Mackenzie Dean, 15, is one such student planning on going to college. He knew he liked math and science, and after speaking with Wargo, he decided to go either into nuclear engineering or quantum physics.

“We had the resources to look at more job opportunities, what it does, how it works and sort of that stuff,” Dean said. “And it made me think more about it. Even just having the ability to do that [is helpful], so you can narrow it down more.”

For high school students interested in college, options such as AP classes or dual enrollment at community colleges help them prepare for that next step and can defray the costs of earning a four-year degree.

Last year, about one in 15 Maryland high schoolers participated in dual enrollment programs at local colleges.

The Blueprint requires local community colleges to accept 11th- and 12th-graders who meet college and career readiness standards and requirements for dual enrollment tuition-free.

Career counselors can also help students make informed decisions about where to go to school, what to study, and how to pay for it, said Carrie Akins, director of Career and Technical Education at Calvert County Public Schools.

“I think people have been hungry for that knowledge for quite some time, but as parents, what they knew was, ‘I don’t want my kid to have thousands of dollars in debt, but I don’t know what to tell them,’” Akins said. “So I think that they’re very excited to now have somebody that can help their child through that process.”

Alternatives to a Four-Year Degree

The Blueprint also requires increasing career preparation opportunities for students who won’t end up going to college. The Blueprint aims to have 45% of high school graduates completing an apprenticeship or industry-recognized credential by the 2030-31 school year.

That’s a lofty goal. Current state data show that, as of February 2023, 27% of high school students had completed a career and technical education program. However, just 7% had earned an industry credential or completed an apprenticeship.

High schools in Garrett, Somerset, Kent, and Caroline counties currently have the highest participation rates in career and technical education, while Prince George’s and Montgomery counties have the lowest, State Department of Education data show.

State-approved career and technical education programs include health professions, early childhood education, dental hygienist and dental assisting, culinary arts, carpentry, cosmetology, air traffic control and many other career training options.

The key to getting students to consider such careers involves reaching them young and debunking some old stereotypes, educators said.

“We really should be starting a conversation of college and career at the K through eight level,” said Ryan Daniel, principal of Fort Foote Elementary School in Prince George’s County.

Such conversations can make a big difference. Northern High School freshman Cody Bach Du, 14, wanted to either go to college for landscaping architecture or go to the Calvert County Career and Technology Academy for woodworking or welding. Talking with Wargo made Duhim realize there were other pathways to sustainable careers outside of a four-year degree.

“When Mr. Wargo came in and he told me about all of these different opportunities, it kind of opened my view up,” Du said.

Given the historical emphasis on a four-year college education, there can be a lingering stigma for students who want to enter the workforce out of high school or opt for job training instead.

“We still need to make sure that we’re doing a better job, really, taking some of that stigma away,” said Chrystie Crawford-Smick, president of the Harford County Education Association, a bargaining union for local education employees. “They’re very lucrative careers and very needed.”

Nikki Phillips, the new advisor at Plum Point Middle School in Calvert County, said some students come to her with a set idea of what success looks like based on perceptions they learn from their parents.

Because older generations were taught that earning a four-year degree was the best path to success, part of the job now involves educating parents on today’s career landscape, especially with factors such as artificial intelligence and automation, Akins said.

It’s a slightly different conversation than the one Phillips has with younger students.

“When we talk about anything in the future, they’re like, ‘I want to be rich,’” she said.

Instead of getting her students to focus on how much money they will make, however, she said she tries to get them to focus on other things, like the quality of life with each job.

“Are you willing to put in the effort to get there?” Phillips said. “Because, no matter what the job is, you still have to go through the effort to get there.”

Capital News Service is a student-powered news organization run by the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism. With bureaus in Annapolis and Washington run by professional journalists with decades of experience, they deliver news in multiple formats via partner news organizations and a destination Website.