John McCain ’13 Soldiers’ featured at Baltimore Book Festival

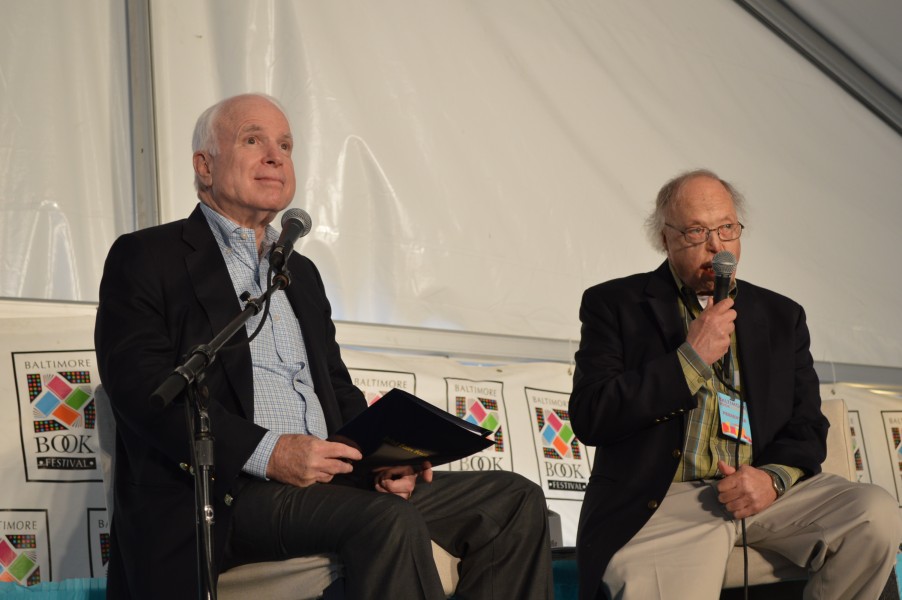

Senator John McCain and journalist Bob Timberg at the 2015 Baltimore Book Festival. (Anthony C. Hayes)

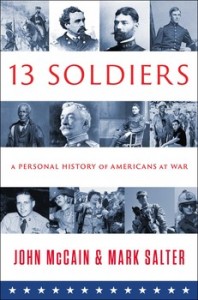

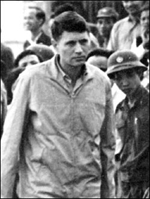

Senator John McCain (R-AZ) was a featured guest at this year’s Baltimore Book Festival. The highly decorated Navy pilot, POW and former Presidential candidate participated in a Q&A about a new book he co-authored with Mark Salter called 13 Soldiers – A Personal History of Americans at War (Simon & Schuster). The following are highlights from that informal interview session with journalist, author and Vietnam veteran Bob Timberg. 13 Soldiers is available in Baltimore at Ivy Bookshop.

BT: We’re here to talk about Senator McCain’s new book 13 Soldiers today, so let me start by asking about the genesis of this book.

JM: Well, first of all, I’d like to thank the Book Festival for having me here, and thank my friend Bob Timberg, a veteran of the Vietnam War and a Naval Academy graduate. He wrote a wonderful book about me and four other graduates of the Naval Academy (Oliver North, John Poindexter, Jim Webb and Bud MacFarlane), called the Nightingales Song. It’s about how the Naval Academy affected us in all of the different aspects of our lives and the offices we held, and in case you haven’t heard – Jim Webb is running for President. It’s also been said, if you are a United States Senator, unless you are under indictment or in detoxification, you automatically consider yourself to be a candidate for the presidency. So I want to thank Bob for what he wrote about us; about the life we led in the 50’s and 60’s and how the Vietnam conflict shaped all of our lives. It’s a very interesting book.

In 13 Soldiers, I tried to portray individuals from each of the major conflicts this country has been involved in; how they interacted with their situation, and how their lives were affected. For example, I write about an African-American named Charles Black, who fought in the War of 1812 and was part of the United States Navy. A lot of people don’t know that in the War of 1812 sometimes as much as 1/3 of the crew were African-Americans, while back on land there were still strong sentiments for slavery and all that accompanied that in those days. So he fought in the Battle of Lake Champlain, which was one of our victories over the British, and many years later he was beaten very badly in a race riot in Philadelphia.

We also tried to bring in the contributions of men like Joseph Paul Martin, who joined the Continental Army at age 15 and went through incredible sacrifices – to someone like Oliver Wendell Holmes who fought and was wounded in the Civil War and went on to be one of our great jurists. We also have women like Monica Lynn Brown, who fought bravely in the Persian Gulf War as a medic, and frankly her performance should resolve any of the controversy whatsoever about whether women can be in combat. The fact is, her example and many other women, certainly in my view and I hope most other Americans believe women can perform equally as well as men, in fact sometimes better.

That’s a long answer to your question, but we want readers to know of the life and experiences and the contributions; the trials and attributes and qualities – no matter the race, gender, station in life. The common aspect in them is that they were willing to serve causes greater than themselves. I think that’s what our lives should be about as much as we can. That’s why we chose (this diverse group of) individuals, to portray to the reader that it doesn’t matter where you came from, what your gender or race is.

The common theme is: you’re ready to serve your country, even if not always gladly or inspired to do so.

Frankly, in the world today – which has not been more in crisis since the end of World War II – I’m sorry to tell you that we may be asking our young men and women to go out and serve and be sacrificed to meet the challenges we face from outfits like ISIS, who behead Americans on the internet and burn a Jordanian pilot to death in a cage. We’re facing a very implacable enemy that would like to come here and attack us. So I’m reminding you that we’re going to be asking young Americans to serve again.

I’m also confident those young Americans will serve with valor, courage and honor.

BT: Senator, forgive me, but my old newspaper roots are catching up with me. If we’re asking young Americans to serve again, how exactly are we going to ask them? What’s the process by which we suddenly recruit young men and young women once again to go out and fight?

JM: Let me remind you that after 9-11, there was probably the greatest upsurge in patriotism in recent history. I’ve met so many young men and women who said, “After 9-11, I joined up”, or “I went into the Peace Corps” or AmeriCorps. There is a famous story, of course, of my fellow Arizonian Pat Tilman who was playing professional football and quit that very lucrative business after 9-11 to join the Army. Tragically, he was killed by friendly fire while serving in Afghanistan. But I believe that when our young Americans see their fellow citizens being beheaded, or whole sections of people being targeted like ISIS is doing to Christians, then I think they will be motivated to serve the country.

I’d like to mention one other story to you that still grips me.

There was a young woman from Prescott, Arizona named Kayla Mueller. Kayla Mueller was endowed with a desire to help her fellow human beings, so she was working in a hospital in Aleppo, Syria as a volunteer. While there, she was captured by ISIS, and after a couple of years she was murdered.

I went to the memorial service for Kayla Mueller in Prescott and saw videos of her saying, “I want to devote my life to serving others; to help the cause of those who are not as fortunate as I am”. I’ll tell you, I will not forget Kayla Mueller, and I will not forget that those people who murdered her are our enemy. And we are going to have to stop them. They want to export that evil to the United States. They don’t want to convert us, but they do want to attack us.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is the leader of ISIS. He was held by us for four years in a prison camp in Iraq. When he was released, on his way out, he told the Americans there, “I’ll see you in New York”. Mr. Baghdadi wasn’t kidding, so I believe young Americans will respond and try to stop this evil which is affecting so many parts of the Middle East and is a danger to spread.

BT: Thank you, Senator. It’s good to know that somebody has that kind of faith in this generation to take on ISIS.

JM: I spend a lot of time with young people; my children and their friends. A lot of the people that I hire to work in my office are young people who have just graduated from college, and I’ll tell you – I believe this generation of Americans is superior in many aspects to my generation. I really do, and I think I can substantiate that by the fact that AmeriCorps is oversubscribed. The Peace Corps is oversubscribed. We have more young people who want to go into the inner cities and Indian reservations to teach than the programs can possibly handle. I happen to think that today’s young Americans are more willing to serve their country than my generation was, and I’m proud of my generation.

BT: (needling) We all know of your son’s service as a Marine.

JM (laughing) Yes, and of the inner service rivalry between the Navy and the Marines. My son joined the Marines at 18, and he came home and said, “You know, Dad – the Marines are part of the Navy. They’re the Men’s Department”. (general laughter) So there you have it.

BT: Senator, to get back to your book. You chose thirteen people from the military, but only three I believe were officers. Two were African-Americans; two were women. It’s fascinating, but I wonder, what was the process you went through in deciding what people you would write about?

JM: Mark Salter – my co-writer and longtime friend – is here with me today. Mark did the majority of the leg work. We sat down and talked about the project; the various things we wanted to include. We talked about the people – some I had heard about, others not. Some had a very close connection. For example, one of the chapters is about a guy named Leo Thorsness.

Leo Thorsness ended up in prison with me in Hanoi. But the reason I wrote about him was the incredible engagement he had as a fighter pilot over North Vietnam, where he literally risked his life time-after-time, because two of his fellow pilots were on the ground. It’s a great story. He fought off MiGs, shot two of them down, got his own plane shot up, and went back to refuel three times in an incredible effort to make sure a helicopter rescue mission coming out of Thailand would be able to reach the two downed pilots.

Leo was subsequently nominated and received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his action. But I met him as a prisoner after he had been shot down a couple of months later by a surface-to-air missile. That’s when he joined us in the hospitality of the North Vietnamese. So Leo is one of the stories which is very close to me.

The other is the story of Pete Salter, who is Mark Salter’s father.

In the Korean war, after the initial breaking out at Inchon, where MacArthur drove almost all the way to the Chinese border and we were over-extended, the Chinese came in and drove us back all the way to south of Seoul. When they struck, that’s where the famous Marine retreat to the Chosin Reservoir took place. Mark’s father Pete was in a company there that was surrounded when the Chinese launched a night attack.

There was a Native American in that company named Mitchell Red Cloud – a veteran of the Second World War. To make a long story short, Mitchell Red Cloud was firing on the advancing Chinese, trying to stop them from clogging the point where the Marines were retreating. He was badly wounded and he asked them to tie him to a tree so that he could keep firing on the Chinese to allow the rest of his comrades to safely retreat. That’s the last Pete Salter saw of Mitchell Red Cloud – of him firing on the Chinese. Pete Salter later got into a hand-to-hand fight with a Chinese solder and ended up having to choke him to death. The next day they ordered the Marines to go back up. It’s quite a story about Mark Salter’s father, and an incredibly brave Native-American named Mitchell Red Cloud, for whom I am happy to say there is a memorial on his reservation in Wisconsin.

BT: One last question, and I hope I’m not asking more than what is reasonable. With every conflict the United States has ever been in, how did you finally choose these thirteen particular people?

JM: We looked for individuals that we thought epitomized the times as well as diversity. Joseph Plumb Martin, who joined when he was fifteen, experienced the starvation and privations of the Revolution from beginning to end. He was the classic example of the young man who not only volunteered but he was also paid to serve. People like Oliver Wendell Holmes who, not only went through the crucible of the greatest blood-letting war America has ever and probably will ever go through, but he also used that searing experience. His father actually thought his son had been killed and went down to tour the battlefield looking for him. Oliver Wendell Holmes used to carry his lunch to the court every day in an ammunition box. He gave a couple of really stirring lectures about the need for war and sacrifice. To me, he was and is the intellectual voice of what the meaning of war is all about.

As I said, we chose one person from every conflict, beginning with Joseph Plumb Martin – to Michael Monsoor, a Seal Team guy in Iraq who, when two comrades were attacked by a grenade, had a choice between saving his own life or the lives of his two comrades. I was at the White House when his family received Mikey’s Congressional Medal of Honor. It’s hard for us to comprehend that sort of sacrifice, but it can only come about because of the incredible bond of friendship and love which is forged by men and women in combat.

Robert Timberg is the author of several books including Blue-Eyed Boy, The Nightingale’s Song, John McCain: An American Odyssey, and State of Grace: A Memoir. A 1964 graduate of U.S. Naval Academy, he served with the First Marine Division in South Vietnam from March 1966 to January 1967. Timberg worked at the Baltimore Sun for more than three decades as a reporter, an editor, and a White House correspondent.