Crosscurrents, Air Quality & Watershed: Spa Day At The BMA

BALTIMORE — When is the last time you visited an art museum? In general, museum attendance is currently at 71% of its pre-pandemic levels. As we continue to navigate through the post-pandemic PTSD, perhaps it’s time to indulge in a museum “spa” day and immerse yourself in the newest offering at the Baltimore Museum of Art. “Crosscurrents, Air Quality & Watershed” fully opens at the BMA on February 26th, though much of the exhibits are available to tour now.

Crosscurrents: Works From the Contemporary Collection, Air Quality: The Influence of Smog on European Modernism, and Watershed: Transforming the Landscape in Early Modern Dutch Art are separate exhibitions. They are, however, all part of the BMA’s Turn Again to the Earth initiative.

Crosscurrents, Air Quality & Watershed is an environmentally-themed exhibition. This thought-provoking presentation seeks to raise awareness of our relationship with nature and sustainability, while challenging the viewer to delve into the connection between artist and the ecosystem around them.

Air Quality reflects on the influence of smog on the work of European artists, such as Matisse, Monet and Whistler. Claude Monet’s “Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect with Smoke” (1903) has a dreamy ethereal quality, despite emanating from a mixture of fog and smog. A chart showing the pollution levels of various cities at different times surprises by showing the astoundingly high levels of pollutants at the turn of the century as compared to Baltimore today.

Crosscurrents: Works from the Contemporary Collection examines how artists in more recent turbulent times use art to express outrage at both geological and political events. This exhibit was not completely open, so this reporter was only able to view a small portion.

By far the most impressive part of the show is Watershed: Transforming the Landscape in Early Modern Dutch Art, highlighting the relationship of 17th and 18th Century Dutch society with the water. The landscape is depicted as a site of economic activity, leisure, and technological advancement, particularly in terms of maritime trade and land reclamation.

Lara Yeager-Crasselt, the BMA’s Curator and Department Head of European Painting and Sculpture – and curator of the Watershed section – took time to give this reporter a personal tour. Lara has been with the BMA for a little more than two years. Previously, she was curator of the Leiden Collection in New York, a private library of Dutch art. She oversaw the scholarship of over 250 paintings and drawings, as it travelled the world.

Lara described the development of the BMA’s Watershed display:

“This exhibition is part of the museum’s environmental initiative over 2025 that was part of the charge given to curators. There’s a process here of really looking very closely at your own collection, and it’s a way to present new narratives around it.

The idea for the show came about very much around the important role of water and land for the Dutch in the 17th century. Watershed is nearly entirely drawn from our painting collection and our prints and drawings, except for a few rare book loans from Johns Hopkins Peabody library and the rare book room of Sheridan library.”

Lara described a painting by Jan Josephsz Van Goyen, “View of Rhenen” (1656):

“I love this detail of the ferry boat. As the Dutch were reclaiming land – shoring up their coastlines, building dikes and canals, creating more fertile land for farming – there’s also just transportation, right? And you have this mix of social classes of the wealthy who have their carriage on the boat, but then also a group of farmers at the front of the ferry. This is what’s happening along the water’s edge; interaction of different social dynamics, of different economic activities happening at the same time.”

In Cornelis Ploos van Anstel’s, “Figures Waiting to Ice Skate” (1766), again this social hodgepodge can be seen.

“And then at left are two winter scenes, and this is what we might think of as associated with the Dutch Little Ice Age, which was this period which encompassed the 17th century and a bit beyond of climactic cooling. That meant that winters were longer. People went out, and they did winter sports and winter activities. You have very elegantly dressed figures on the edge of the ice. You have people standing, people sledding, people probably on their way to work, people playing games. The ice became such an interesting part of the landscape in which all social classes all coexisted, which is something of a unique sight in this moment; a role that the landscape could play in telling that part of the story.”

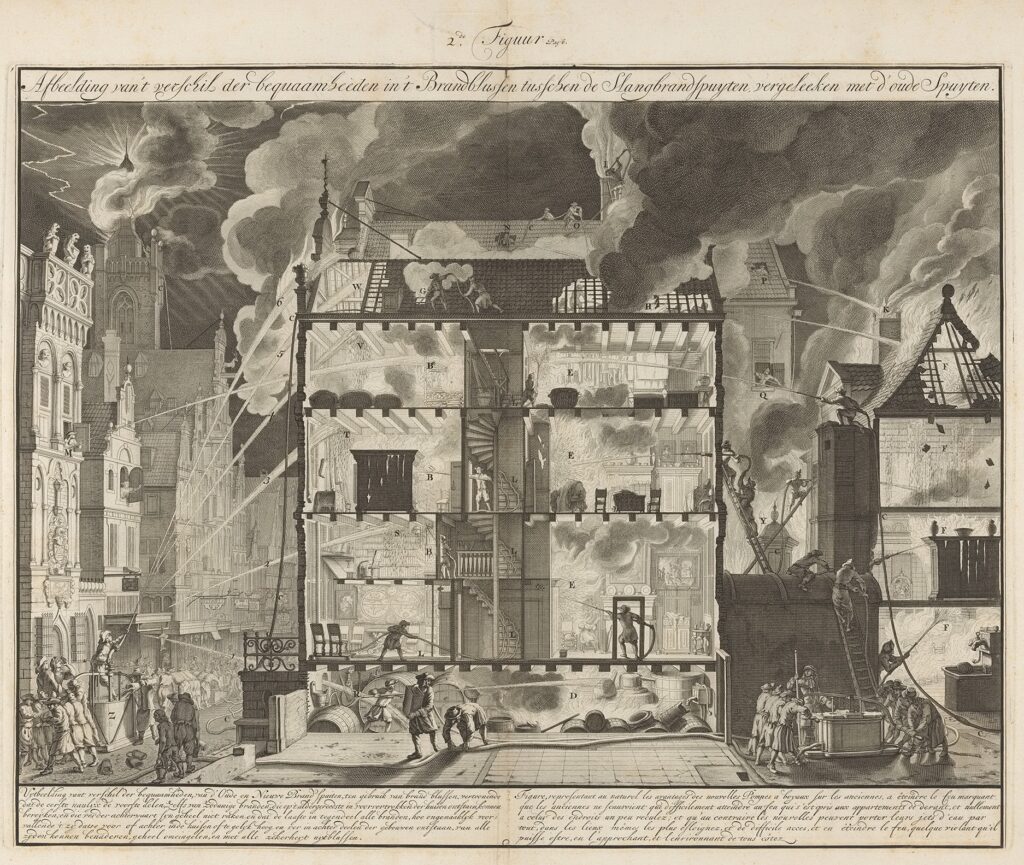

Another aspect of utilizing the water is interestingly demonstrated in an enlargement of a sketch by Dutch artist, Jan van der Heyden, the inventor of the fire hose.

“Here you see a burning canal house and this juxtaposition between the old way, using buckets from the canal and then putting them in a bigger bucket and trying to spray; versus actually having a fire hose, which has enough power to pull water directly from the canal and then more effectively fight the fire.”

I asked Lara about her reflections as to how she constructs such an impressive production.

“For me, it’s very much an iterative process of working through your big idea. I had certain works which I knew right away that I wanted to have them in, because they would start to support and illustrate some of my points. And then, it’s a process of looking through the collection of the paintings. There were a lot of exciting discoveries, and then trying to understand, what fits in this section or that section? Does it help to tell my story about the importance of trade for the Dutch? Also, I wanted to show this stylistic change from the 16th to the 17th century, so you end up building different layers. It was really important for me to include atlases, maps and cartography. That was crucial, because that’s another way artists depict the land, a way of controlling the geography.”

The “Crosscurrents, Air Quality & Watershed” presentation certainly leaves the visitor with a lot of questions to ponder regarding, not only the artist’s relationship with nature, but our own intricate bond with our surroundings. The artists’ vivid portrayals of our ever-changing ecosystems illuminates how people lived in the past but also serves as a call to action, urging us to recognize the impact of environmental shifts on our daily lives. This thought-provoking exhibit not only highlights the beauty of our natural world but also challenges us to reflect on our role in preserving it for future generations.

* * * * * *

To complete your museum “spa” day, why not rest your museum feet by sitting down to a lovely lunch at Gertrude’s restaurant, located next to the gift shop at the BMA? Gertrude’s offers a delightful array of everything from brunchtime favorites to elegant dishes. I sampled the pea soup and Mediterranean platter, while my dining companion had a side salad and the Chesapeake Rockfish Imperial. We suggest you grab a side of the fries; so good. Though we had a surprisingly surly masked waiter, everyone else was very helpful and friendly, and the food and drink were satisfying and tasty. Highly recommended.

(This story was updated to make clear the delineation between the separate exhibitions.)

Copyright 2025 Baltimore Post-Examiner. All Rights Reserved

Lisa Salkov is a quizzical Renaissance woman — paralegal, actress, award-winning playwright, journalist, editor, loyal friend, and cat fancier. Above all, she is a soprano who thrives in sacred spaces. Lisa follows her curiosity wherever it leads — health and wellness, philosophy, religion, humor, and the human condition. As she gracefully enters yet another season of life, Lisa is grateful to care far less about the things that never really mattered.