Code Red Part 3: No trees, no shade, no relief as temperatures rise

Lorraine Diggs stands on the sidewalk outside her rowhouse in East Baltimore on July 9, 2019. Diggs is passionate about maintaining the trees outside of her home and has dedicated a small garden in front of her house to her late mother. University of Maryland Photo/Maris Medina

By Roxanne Ready, Theresa Diffendal, Bryan Gallion and Sean Mussenden

Capital News Service

Kwamel Couther stands on the front lines of a campaign to bring thousands of cooling shade trees to some of the hottest streets in Baltimore.

City trees are especially vulnerable in the first two years of life, requiring about 20 gallons of water per week to stay alive. Couther, who supervises a tree maintenance team for a Baltimore tree nonprofit, intervenes in case the clouds fail to provide.

He needs a lot of water, too, as he works in the summer heat on one of the city’s hottest — and poorest — blocks.

In a city marked by inequity, leaf cover is just one more thing that has been historically distributed in unequal measure. The city’s poorest areas tend to have less tree canopy than wealthier areas, a pattern that is especially pronounced on the concrete-dense east side, in neighborhoods like Broadway East.

“The trees that we planted so far aren’t providing that much shade,” Couther said of the new arrivals on this street. “Yet.”

The question of whether these trees — and thousands of other recent arrivals — will ever provide enough shade is critical to the health of people in Baltimore’s hottest neighborhoods, as they face a future of increasingly intense summers, driven by the climate crisis.

Trees could be a solution to Baltimore’s heat islands

The urban heat island effect makes Baltimore hotter than the surrounding suburbs. A major reason: many of the materials that define Baltimore’s urban landscape — brick rowhouses, concrete sidewalks, black tar roofs, asphalt streets — are very effective at trapping, storing and then radiating heat.

To cool neighborhoods, you could remove those materials or replace them with heat-repellent versions. Or you could prevent some of the sun’s heat energy from reaching those materials in the first place. Trees — especially dense clusters of large trees with expansive canopies, like those common in Baltimore’s wealthier northern neighborhoods — offer the best hope for doing that.

This helps partly explain why in Baltimore, the coolest neighborhood has 10 times more tree canopy than the hottest neighborhood. In temperature readings taken by researchers at Portland State University in Oregon and the Science Museum of Virginia on one particularly hot day in August 2018, there was an 8 degree Fahrenheit difference between the coolest and hottest neighborhoods in the city.

“If you live in a … city that is seeing more extreme heat days, but you don’t have tree cover to cool down your neighborhood, that can literally be a life or death issue,” said Jad Daley, president and CEO of American Forests, a nonprofit working to expand urban tree canopy in an equitable way across the U.S. “Bringing tree cover into neighborhoods can cool what we call ‘urban heat islands’ dramatically.”

U.S. cities are losing 29 million trees every year, and many cities are struggling to reverse their dwindling canopies, according to an investigation by NPR and the University of Maryland’s Howard Center for Investigative Journalism. Between 2009 and 2014, 44 states lost tree cover in urban areas, according to the U.S. Forest Service, though Baltimore bucked the trend with a small increase between 2007 and 2015.

The city’s forestry division, nonprofits like the Baltimore Tree Trust, neighborhood associations and others have spent the last decade aggressively working to expand the city’s tree canopy.

They’ve collectively spent millions of dollars and thousands of professional and volunteer hours to increase planting across the city, targeting some of the poorest neighborhoods. Just as critically, they’ve spent millions more doing vital maintenance work to keep new and old trees healthy, nurturing them through young adulthood and caring for them as they age.

Trees are ‘critical infrastructure’

“Trees are not just scenery. They’re critical infrastructure for the health and wealth and well-being of communities,” Daley said. “[Distributing] the cooling shade of trees more equitably across our cities is an absolutely essential strategy. We like to say hashtag tree equity equals hashtag health equity.”

Trees are an effective cooling solution, but are not a quick fix.

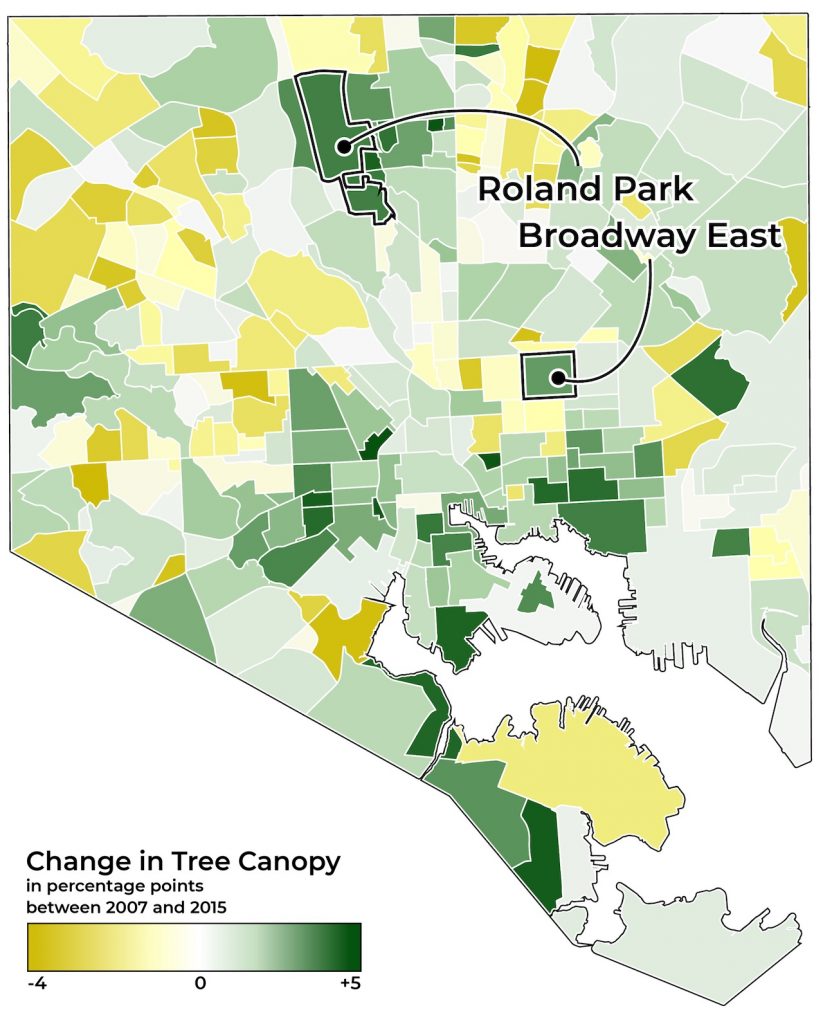

Between 2007 and 2015, tree canopy in Broadway East grew from 9% to 10.6%. Roland Park, a wealthy northern Baltimore neighborhood already covered with trees, grew by 2.1 percentage points to 64.5%.

The city’s tree canopy is fluid like this. It grows when new trees are planted and existing trees grow larger. It shrinks when trees are trimmed back — or even removed — to accommodate city life, when limbs fall during storms, or trees die from disease or other causes.

“Baltimore is one of those few places where the growth and the planting has outpaced the loss,” Grove said, pointing to an increase in the city’s tree canopy from 27% in 2007 to 28% in 2015.

Those gains and losses were not distributed equitably. About 40% of city neighborhoods had net losses. The rest had net gains, but the increases in Baltimore’s hottest neighborhoods didn’t come close to correcting the inequity.

For Daley, of American Forests, a city’s overall level of canopy cover is less important than the numbers in each neighborhood — and the differences between them.

“A simple percentage for the whole city … can mask those inequities,” he said. “Whatever the right level of the tree canopy is for a given city, given its climate and its setting, we should hit that same mark in every single neighborhood. And we have a lot of work to do to bring, particularly, low-income neighborhoods and communities of color up to that citywide standard.”

Jake Gluck and Jane Gerard of the University of Maryland and Meg Anderson and Nora Eckert of NPR contributed to this story. The Code Red series is a collaboration among the University of Maryland’s Howard Center for Investigative Journalism, Capital News Service and NPR.

MarylandReporter.com is a daily news website produced by journalists committed to making state government as open, transparent, accountable and responsive as possible – in deed, not just in promise. We believe the people who pay for this government are entitled to have their money spent in an efficient and effective way, and that they are entitled to keep as much of their hard-earned dollars as they possibly can.