Mosaic project bridges gulf between Baltimore police, city youths

(This story originally appeared in Equal Voice News, published by the Seattle-based Marguerite Casey Foundation. It is republished with permission.)

On a sunny Monday afternoon in early April 2015, 18 teenagers – all veterans of the juvenile justice system – sat in a circle with seven Baltimore City police officers inside a dance studio at a strip mall on the city’s west side.

A “Peace Circle” – in which the officers and youth sought common ground, trust and understanding – began each of the five days that the group worked on an intricate, circular, 5-foot-diameter mosaic.

The youth-focused Choice Program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), brought together the officers, young people, AmeriCorps student volunteers at UMBC and Carien Quiroga, a professional mosaic artist who teaches art at juvenile facilities throughout the state and led the effort.

Together, they arranged thousands of mosaic tiles and shards of metal and glass into a montage that includes shapes of police badges, a peace sign, flags, a heart and two hands clasping each other. The fledgling artists named their mosaic “Uprising to Artrising.”

The mosaic, demanding justice for African Americans killed by police in America – including the 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, which galvanized the Black Lives Matter movement – was to be installed within weeks of completion in the foyer of the Baltimore City Police Department Headquarters.

But the death of Freddie Gray in police custody in West Baltimore – and the searing aftermath that tore this city apart – delayed the plan by two years. Still, Choice leaders remained determined to have the mosaic displayed at police headquarters.

Now, two years after its completion, the mosaic will be hung during a June 20 ceremony. The Choice Program’s director, LaMar Davis, credits first-term Mayor Catherine Pugh, a Democrat who took office in December, and Police Commissioner Kevin Davis with finally helping make it happen.

From Suspicion to Connection

Its name notwithstanding, the 2015 “Peace Circle” at first seemed more like a circle of suspicion and mistrust, with smirks and silent stares, participants recall now. Gradually, though, the daily exchanges and shared effort that took place during the “Spring Break Mosaic Project” helped police officers and young people find common ground.

Shanaya, an 11th-grader at Frederick Douglass High School who entered the juvenile justice system for fighting at school, recalled looking at the officers that first day in the “Peace Circle.” She thought of Black friends and relatives who had been harassed, stopped and frisked, ordered to lie on the ground, or detained by police.

“And then there are some bad cops who beat people on the street, or even kill people, without good cause,” said Dodd, 16, who has three dogs and plans to become a become a veterinarian.

But by the end of the week, she said: “This project changed me. It took a while, but we kind of saw how the officers were really cool once you got to know them. You know, what surprised me the most about the police? It was just how nice they were once you got to know them.”

The mosaic itself is an attention-seizing explosion of shiny, metallic hues: oranges, deep blues and purples, reds and greens, interspersed with white mosaic tiles to form a dramatic contrast.

Its creators chose a “Peace Circle,” representing unity and inclusion. An undulating line bisects the circle. On either side of the line are three dark pyramid shapes of equal size, mirroring each other, representing balance. The completed work brings together the shards of life each participant contributed into an interconnected mosaic, signifying unity.

More than a little proud of their handiwork, the officers and young people had every reason to believe the mosaic, spread over lightweight cement composite, would hang at city police headquarters downtown by the end of the 2014-15 school year.

Then, two days after the mosaic’s completion, 25-year-old Freddie Gray suffered what would prove to be fatal spinal injuries while in police custody, wearing shackles (but not departmentally required seat belts), as he bounced around the metal cage in the back of a police transport van on a circuitous, 45-minute journey.

The day after Gray’s April 27 funeral, angry teens hurled rocks, bricks and bottles at police outside Mondawmin Mall, igniting rioting that quickly swept across the city. Protesters set fire to hundreds of businesses, torched scores of cars and looted stores.

Republican Gov. Larry Hogan called in the National Guard and declared a state of emergency. The police commissioner resigned, and Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, once a rising-star Democrat harshly criticized for her response to the rioting, ultimately decided against seeking re-election over the fallout.

With city leaders in crisis mode, the initial enthusiasm for hanging the mosaic at police headquarters seemed to evaporate. Police brass and City Hall were consumed by ongoing protests; the trials of six officers; scathing state and federal investigations; and a multimillion dollar civil suit brought by Gray’s family.

A Dream Attained

Quiroga, the mosaic art teacher, says the young people involved could hardly contain their enthusiasm over completing the mosaic.

Now, at last, their work will hang in the very nerve center of the Baltimore City Police Department.

“We had so much initial tension, and then the relationships between the kids and the police changing as the project changed, as sheets of glass were broken into smaller pieces and then put back together to create something beautiful,” the White, South African-born artist said.

“What was broken has become pieced back together, made whole – in the art, in the relationships.”

But not right away.

Early on in the week-long process of creating the mosaic, a Black teenage boy from a violence-plagued neighborhood piped up with a question for one of the officers:

“How come every time we see a police officer in our neighborhood, he’s locking somebody up? That’s the only time we ever see them.”

Officer Lawrence LaPrade, who is Black, told the teen he knew something about living amid violence and poverty and drug dealing, in a place where you knew seeing cops could only mean trouble.

The officer had grown up in the notorious Lexington Terrace housing projects, a sprawling complex of high-rise towers demolished in 1996.

“Unfortunately, these youths in the ‘Peace Circle’ that day only saw the police when they were locking people up,” LaPrade said recently. “There are trust barriers, and that’s what we’re working to change.”

LaPrade told the youth, almost all of them Black boys, that while growing up in the Western District, he decided he would return to work as a police officer there.

He was eager to participate in the mosaic program, to do his small part to help reverse the cycle of violence, poverty and despair in a city that had more murders through May of this year – 146 – than during the first five months of any year in its history.

“I grew up here, and I came back here to give back, to help save it,” he told the young people.

“These are still kids”

Through the mosaic project, participants said, officers and youth got to know about one another’s lives, hopes, aspirations and hardships. Labels and stereotypes slipped away. The kids and the cops shared stories and laughter as they got to know one another as individuals, not merely seen as just another delinquent on the path to a life of crime, or another bad cop.

“It helped show me these are still kids,” LaPrade said. “There are still kids inside them who need to see that we’re there to help them….We opened up to them, and they opened up to us.”

In some neighborhoods, LaPrade said, this kind of communication is rare, if not impossible: “The parents don’t even want the kids to say hi to the police. They tell their kids, ‘Don’t speak to them. Don’t go near them.’”

“It’s good for them seeing us doing something other than arresting someone,” LaPrade said. “That’s when they see us most of the time.”

Trying to Stop the Bloodletting

Baltimore’s absolute murder numbers through May of this year trail only those of Chicago, which has five times as many people. Baltimore’s per-capita murder rate far exceeds that of Chicago, New York and other big cities often associated with violent crime.

Now, amid one of the deadliest stretches in the city’s history, from City Hall to Fells Point pubs to the Catholic Charities homeless shelter by the Jones Falls Expressway ramp, the talk of this old port city of 620,000 is centered on how to stem the bloodletting.

Mayor Pugh has asked the Trump administration to send in reinforcements from the FBI to patrol city streets. But even as politicos call for tougher enforcement, the crime wave has underscored the notoriously bad relationship between city police officers and residents of the poor, Black neighborhoods they patrol.

In this sense, the mosaic project, completed two years ago, appears prescient.

The year opened with Pugh, just weeks into her term as the new mayor, and Commissioner Davis announcing that 500 city police officers would undergo group and individual training sessions and meet one-on-one with middle school youth to try to break down barriers between police and teens.

“The most important thing we learned through the unrest is we need to repair the relationship between the police and young people,” Baltimore City Councilman Brandon Scott, a Democrat, said when the initiative was announced at the nonprofit Community Mediation Center, which is overseeing the training sessions.

“There is nothing more important to repair in our city than that relationship.”

Mayor Pugh sounded much the same theme during a June 10 “Call to Action” aimed at stopping the violence. The mayor stressed the need for police to strive to engage youth, even – perhaps, especially – those who distrust police.

City Police Lt. Col. Melvin Russell, commanding officer of the Police Department’s Community Collaboration Division, says outreach efforts can make all the difference when a cop encounters a youth.

Russell, who led the department’s effort to bring officers and youth together for the mosaic project, pointed to other department programs like camping trips during which police officers sleep under the stars with teens in parkland on the outskirts of the city; peer mentoring and peer conflict-resolution programs; and the “Explorer” program, which puts students on track to become police officers.

“It all about just engaging the kids,” Russell said. “It is an art, listening to the community, connecting with the kids one on one. You build buy-in as a friend, someone they trust, when you do that. We have to talk to kids so they’re not looking at the police as their enemy.”

Russell said the mosaic project went a long way toward that end and that he’s confident it will resume next spring.

Chantell English, another city police officer who worked with the youth on the mosaic, said she has no doubt the officers and teens built something even more than the mosaic: trust.

None of them, she said, would ever revert to seeing just another juvenile offender destined for a life of crime, or just another bad cop out to harass Black teens on the corner.

English knew the teens in that West Baltimore dance studio felt the transformation, too. She could tell by their easy laughter, the way they shared bits of their stories with officers or asked police for advice, their obvious pride in creating something that stood for peace, harmony and justice.

“They’ll go back to their friends and say, ‘You know what, these officers weren’t that bad,’” she said. “‘They were actually all right.’ And in these neighborhoods we’re working, that means everything.”

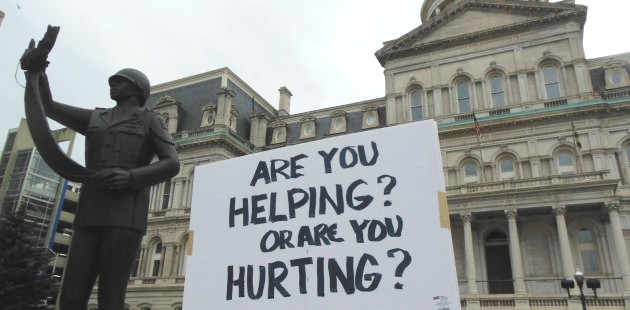

(Top photo of a sign outside of Baltimore City Hall during the April 25, 2015 Freddie Gray protest. Credit Anthony C. Hayes – Baltimore Post-Examiner)

Gary Gately, a seasoned journalist, has won 15 national, regional and local awards for reporting and writing news, investigative, public service, feature, business and travel pieces. Gately’s work has been published by The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Baltimore Sun (where he worked in reporting and editing jobs for 11 years), Baltimore Examiner, the Chicago Tribune, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Guardian, The Washington Post, The Dallas Morning News, Business Week, Newsweek, Arrive Magazine, The Center for Public Integrity, CBSNews.com, CNBC.com, ABCNews.com, USAToday.com, HealthDay, The Crime Report, United Press International and numerous other newspapers, websites and magazines.

His coverage has received awards from the Associated Press, the Society of Professional Journalists, the Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild, the Maryland-Delaware-D.C. Press Association and the Society of American Travel Writers (first-place Lowell Thomas Award for best newspaper travel story/U.S.-Canada (immigrant New York).

Gately also has extensive experience editing for newspapers and websites, has taught college journalism courses in news writing, magazine writing and travel writing and is the author of Maryland: Anthem to Innovation, a book on the state’s history, industries and attractions.