World War II memories that never will be forgotten

The following story is a Memorial Day homage to a soldier. These are first-hand accounts, not gruesome, but amusing in their insight into one man’s slice-of-life recollections about his experiences in WWII. That man was my dad, Roald Borge Forseth.

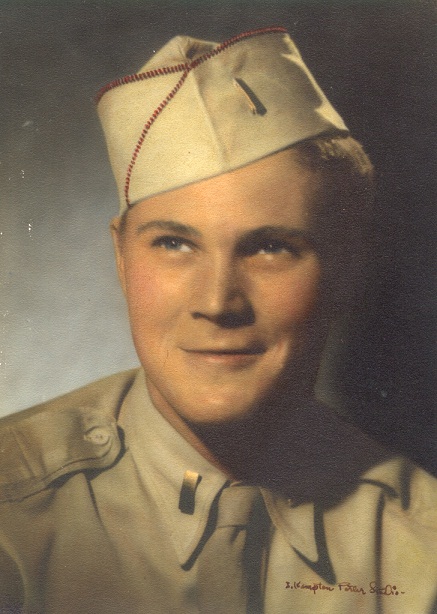

Roald was drafted into the U.S. Army as a private. He left the Army with the rank of second lieutenant.

He once said of his time at war, “It was the biggest waste of five years of my life.” Those words surprised me when I first heard them, in my teen years. I responded that he was defending democracy and defeating dictators. Roald never countered my retort. Rather, he just stood silently, his gaze falling to the floor, like he was thinking about something deeper than I could comprehend.

He often played his cards close to the vest, particularly regarding his experiences with the horrors – and absurdities – of war. Later, I came to realize that he likely saw war, overall, as a waste of the time and resources of all those involved in the gruesome game. I’m fairly certain that, after I had grown to know his philosophical tendencies, Roald mostly despised those crazed fools who instigate wars.

A word of thanks to my brother-in-law, Richard O’Hara, for having transcribed so many of Roald’s recollections (circa 2005), gleaned from Richard’s rapt and patient interviews. I vouch for the transcriptions plagiarized (with Richard’s permission!) herein, having heard Roald long-previously recount the same stories in the 46 years I shared with him as his son.

Training? What training?

In 1919, Roald was born in, then later drafted out of, Wisconsin. His draft number came up in October of ’41. He rather enjoyed Wisconsin. After the draft, things got weird.

Following some basic training, he was shipped to the Aleutianswith the 250th Coast Artillery Regiment, a California National Guard outfit.

“I was a replacement, newly drafted, barely trained and I didn’t know anybody. It’s hard to fit into an outfit full of guys who have been together for a long time.

“We shipped out on the S.S. Cherokee,” a 5,896-ton steam passenger ship, built in 1925 inVirginia. Nautical records show that the Cherokee had a top speed of 15 knots. (A German U-boat near Halifax, Nova Scotia, torpedoed and sank her on June 15, 1942.)

Of his pleasure-cruise to Alaska, Roald says, “It was just hell. The Cherokee was not a large ship at all. It had been used after WWI in the fishing industry, hauling boxes of canned fish and supplies for the canneries.”

Given the Cherokee’s leisurely top speed, “once we got out of the intercoastal waters and into the Bering Sea, there were days it seemed we didn’t make any progress at all. We could really study the glaciers as we headed north. The wind, waves and currents were too much for that old ship. It took forever to get to the Aleutian Islands.

Oddly enough, accommodations and sleeping quarters on the Cherokee lacked that passenger-ship charm when it was packed with poor slobs headed to war.

“We were kept in the hold, and slept in bunks stacked five high. The bunks were in long rows, so your feet were always in somebody’s face or their feet were in your face. To escape that indignity, you tried to curl up on those sling bunks. But the mattress was narrow and sagged in the middle, so you could never really get comfortable.”

This alleged “passenger ship” also lacked the modern conveniences of environmental controls most of us enjoy in our daily lives.

“The stench was just horrendous. It was like a slave ship. All that sweat and body odor and no ventilation. The only fresh air came in when the crew would open a hatch, and then there would be this blast of Arctic wind, which just seemed to make everything smell worse. Of course there were guys vomiting all the time, especially in bad weather, and we had a lot of bad weather. This was the North Pacific in winter.”

Come and get it!

“When the ship got to really rolling, things got worse. Then you could hardly make a meal, do dishes or even eat. Guys couldn’t make it to the head, so they would be vomiting in their beds or in their shoes. You couldn’t ever take a shower or get your clothes clean, so guys were walking around with dried puke on their shirts.”

Powder your nose, burn your butt

“The head was the worst. It was primitive and insulting. They had a long bench in one room, with a half dozen holes in the bench and a trough underneath. The trough was supposed to drain through holes in the bulkhead that had flipper doors on the outside. I suppose this might have worked when the ship was in harbor, but out in those seas it was just a mess.”

What, you ask, could make matters in the ship’s head such a mess?

“The roll of the ship would tilt the filth one way and then the other. It couldn’t get out because the flipper doors would close whenever that side of the ship was underwater. In heavy seas, all the crap would rush over and hit the bulkhead and spray into the air. Then the ship would roll the other way and the same thing would happen on the other side. You can imagine what was flying around. It was a total nightmare. It’s a wonder we didn’t all get cholera.”

And, of course, every luxury liner has its jesters.

“Even in relatively calm weather the head was an ordeal. You’d be sitting there, and some poor soul would wander in and puke into the hole next to you; just a steady stream of horrible-smelling vomit. Or someone down at one end would wad up a big bunch of toilet paper, soak it in lighter fluid, light it, and send it sailing down the trough. Guys would leap up with burned butts, and everyone would have a big laugh. Not exactly a cruise ship.”

Kohler’s inspiration?

“The final outrage was when they made us take a shower. I guess they wanted us to look our best when we landed in the Aleutians. They marched us up on deck and made us strip. Then they gave us soap and hosed us down with salt water straight out of the Bering Sea. That water is actually below freezing, and they gave us regular soap, not saltwater soap, so we didn’t get clean, just kind of gummy. I’ll never forget that.”

Forward, men! To the past!

In the Aleutians at that time, much of what the troops had for equipment amounted to hand-me-downs from WWI. General Buckner was busy soliciting Washington for modern-warfare materials, but DC initially didn’t seriously think Alaska was at risk of attack. Washington was focused on helping the Allies.

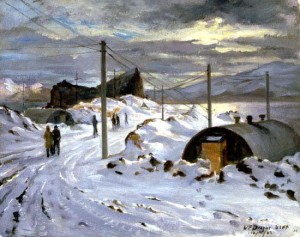

“The Aleutians were all bad. Rain, mud, snow, rotten food, poor equipment, bugs, rats, holes in my shoes; the whole stinking mess. But the wind was the worst. It exaggerated every problem. The wind was noisy, ferocious, and constant. Ninety-mile-an-hour blasts were common. The volcanic rock was so light that chunks of it would fly through the air. Grit stung your skin and coated everybody and everything. You couldn’t even look at the wind when it was blowing bad.”

Roald says tents didn’t last long; they’d get shredded by the volcanic-sand-blaster winds and related unidentifiable flying objects. Quonset huts were the standard.

“We were lucky. Our Quonset Hut never collapsed. We were up on the mountain, and the hill behind the hut saved us from the weather coming from the west. Huts in the open were always falling down, and tents wouldn’t last beyond a month. When the huts collapsed, sheets of corrugated steel would fly through the air.”

Roald often joked that, in the Aleutian Islands, “there’s a woman behind every tree.”

“There were no trees on Unalaska Island, but we had logs of compressed wood chips for the Sibley stove. They came in on Florscheim’s yacht. The wind pulled air through the [Quonset hut] chimney like a vacuum pump. A load of logs would burn furiously, and turn the stove cherry red. Then the stove pipe would turn red, and the intense heat would drive everyone to the far corners of the hut. In a little while, the fire would die down, and the cold would creep in, and we’d crowd closer to the stove. That’s the way it went every night until we crawled into our bunks.

Initially in Alaska, the enemy wasn’t human.

“When a guy went out for logs, someone went along to handle the doors. The inner door led to the entryway. The outer door would rip off the hinges unless you braced it against the wind. The logs were covered with snow, and carrying an armload was an adventure. We always sent two men when we went outside. A twisted ankle, a flying piece of tin, or a simple fall could easily disable a man. We were always hearing about guys freezing to death for some dumb reason. Mostly we tried to survive, while Alaska and the Army tried to kill us.”

Whips and jingles

As expected, random gatherings of people plucked from various parts of the world will include in the strange mix of humans a few exceptionally curious ones.

“Our outfit had its share of misfits, and I guess I was one of them. One of the standouts was a guy we all called ‘Whips and jingles.’ He wasn’t too smart to start with, and he had all these little ticks and oddities. When he walked, talked, sat or slept, he was always jerking in funny little ways. ‘Whips’ had a habit of shouting until a crowd gathered, and then throwing a handful of nickels, dimes and quarters into the air just to see everyone scramble. This was after he had enough to drink, and he always had enough to drink, even if it was nothing but vanilla extract. He always wanted to find some drug or alcohol so he could ‘get to that higher level.’

“When ‘Whips’ was loaded, he talked so fast that half the words were omitted. The last sentence would sound like this: ‘En loada talks s’fas haf urds mitt’d.’

“He never bothered with trivial words, and often was so anxious to get to the next sentence that he didn’t bother to finish the sentence he had already started. One night he came in about 10 o’clock and started jabbering. Everyone went to sleep, but he kept at it. About 1 o’clock, one of the boys woke up and heard him still jabbering all to himself. Three o’clock – the same thing; more speed, less volume. What a man! Yet, it’s guys like him who kept all the others from getting too bored with the place.”

Alchemy, anyone?

“We trekked down to Dutch Harbor one day, at Whips’ suggestion, because we heard that the civilian store was closing down, and “Whips” wanted to see what they had. He convinced us to buy cases of canned-heat SternoTM and big cans of grapefruit. Back in the hut, he showed us how to squeeze the Sterno through a sock – preferably clean – and then swallow the extract with a grapefruit chaser. I survived, ‘Whips’ got to that ‘higher level,’ and we all woke up the next day with splitting headaches.”

USO to the rescue

“Sometime in August we finally got a USO show. No babes, just Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy (with Mortimer Snerd). I sat up front so close I could have spit on McCarthy’s shoes, but I didn’t. Some strange force held me back.”

The Stone Age

“We were supposed to be an anti-invasion artillery battalion, which means we would blast ships, landing craft, and beaches if the Japanese ever attacked.

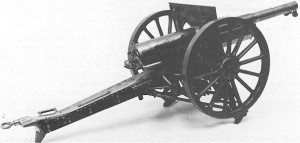

“We started out with French 75-millimeter artillery pieces, which had iron wheels and were old and worn out. We looked like WWI Doughboys with those French 75s and our flat tin helmets – ‘pee pot helmets,’ we called them – and bolt action rifles, and wooly uniforms. I guess the brass finally figured out that we needed better artillery when the wheels started falling off the 75s.”

The Modern Age?

“The 155 Howitzers were brought in. They shot bigger shells, but were in pretty sad shape. The barrels were all worn out, and they’d blow out big smoke rings whenever we fired. When the battery would salvo, the rounds would fall all over the place.”

Practice makes perfect

“When we’d get a break in the weather, the Navy would take us to various places around the island. We’d survey the bays and beaches, and then set up our observation posts. The 155’s back on the mountain would lob in a few shells, and we’d try to figure out the right settings to bring the shells in on target.

“As they’re heading toward you, those 155 shells sound like a boxcar flying through the air. They would splash all over the bay and carve up the beaches. All we could figure out was the range, because those Howitzers just couldn’t shoot straight.”

Welcome Wagon run amok

“We once fired a warning shot across the bow of an incoming ship. It turns out that it was full of ammunition and was being escorted by a destroyer and a submarine. Our recognition codes had recently been changed, and the U.S. convoy hadn’t picked up the changes. They rounded Captain’s Point and we challenged them right away. When they couldn’t give the correct response signal, we were ordered to fire. The shell passed right through the rigging of the ammunition ship, and that ship stopped dead in the water, just like it had hit a rock. That was the last time a ship made that mistake.”

Saving lives

“One day we were aboard Florscheim’s yacht, coming back from one of those surveying parties. The wind was howling, and the boat was coming in on a rip tide. The water was extremely turbulent. The pilot was warning us that we would probably swamp as we came to shore.

“We had a guy on board who was susceptible to seasickness. He would turn green just watching a boat from the shore. The yacht was rolling all over the place, and he went to the rail to heave. The boat rolled to his side, and he started pitching into the water. He was so sick; he probably didn’t even know what was happening. I ran to the rail, grabbed a stanchion, and pulled him out of the water. We were just soaked, and he was still puking. Green vomit was spewing past my nose. I knew then that I’d never be seasick again. I got some other guys to help, and we pulled him into a cabin where he’d be safe. I got no thanks. Nobody had any energy. The rescued guy just gave me a weak, ‘That’s O.K.’

“On the face of our mountain, we built an observation post about 300 feet down the cliff. We had a 30-power scope down there that had azimuth and range markers in it. It was a steep cliff, about 15 degrees off the vertical.

“The only way we could get down was on a skid, a kind of a pallet about five-foot square. This was lowered down the cliff on two cables, which ran out of a winch. Two guys would go down at a time, hanging on for dear life.

“We carried sticks with us to fend off the rocks, which were always tumbling down on us. At the end of the cable you could get a foothold on a ledge we had carved out, and make your way to the post. That cliff continued down from the ledge to the ocean about 500 feet below.

“Coming up the cliff one day, the cable hooks snagged a big slab of rock and down it came. My buddy tried to use his stick, but the rock was too much.

“He was knocked off the skid, and started tumbling down the cliff. I took a leap and a couple giant steps and caught up with him. He was dazed. I dug in my heels, and waited for the guys up top to figure out what was going on.

“The skid came down, and they pulled us up.

“I never got anything for it; no medals, no letters of commendation. But I get a lot of satisfaction out of it. I saved two lives, and not everybody gets to do that.”

Zapping rats

“As summer approached, we got more bugs, rats, rain and mud. The rain flew sideways in the wind, the horseflies were voracious, and the rats were everywhere. Every ship brought in more rats. They had no natural enemies, and there was garbage all over the island. Those rats dug through the floors to get into our huts. They must have smelled the food, and a rat will kill itself to try to get food. We wished we had a dog, but only the officers had dogs.

“I woke up one night because something was crawling on me. I looked up and saw a hairy Norway rat sitting on my chest. I flinched, and the rat sprung at me and bit my nose. I roared, and the rat ran. We didn’t have any medical facilities, so I didn’t have to go through the agony of rabies shots, just the uncertainty of wondering whether I’d get rabies.”

Roald wasn’t about to let a rat get away with assault. Not without a little high-tech justice.

“I wanted revenge, so I rigged up a deadfall in our hut. I baited it with garbage, and used a pitchfork powered by a stretched inner tube to try to spear the rat. He was too fast, and always snatched the food without getting hit. I figured I’d try something different. I’d use electricity. Nothing can outrun electricity.

“I tapped into a 220-volt line coming out of the ceiling. Then I set up the trap so that the rat would complete the circuit when he grabbed the garbage.

“That worked. There was a big flash, and the rat bounced a few times as he was electrocuted. Unfortunately, the hut stunk for days, and the guys all got mad. But I got the rat.”

Welcoming the enemy

“We were bait ourselves; bait for the Japanese. They finally came on a clear day in early June, just before sunrise. We were ready.”

It turns out that three weeks before the attack, the U.S. intercepted a secret Japanese message about the Japanese plan. The Japanese were surprised by the anti-aircraft fire that met them, but managed to damage the Margaret Bay Naval barracks, killing 25 servicemen.

“When the alarm sounded, I ran down the hill to the battery office to get orders. One foot caught in the muck, and the other one slid. My left knee jammed up and split the cartilage under the kneecap. I didn’t have time to worry about that, so I kept going.

“There wasn’t much we could do except get into our foxholes. A 155 Howitzer can’t fire at planes. We watched the Japanese bombers and fighters attack the ships and the base at Dutch Harbor. One of our scout planes took off from the bay and headed our way. It was a biplane with a gunner in the back. He fired his puny .30-caliber machine gun at the nearest planes, and the pilot did his best to hug the ground and zig-zag up the mountain. We thought it was funny, and laughed about it for days. That plane looked like a scared rabbit.

“We got off a few shots with our rifles. The Japanese pilots were also scrambling for the mountains after they pulled out of their dives. As they passed by they were only a few hundred feet over our head. The attack only lasted 20 minutes, and the Japanese only lost one plane. We lost a whole barracks at Fort Mears, and most of the guys in it.

“The Japanese came back the next afternoon. We had been ready all day. They bombed an old ship, which had been beached at Dutch Harbor. Then the fuel tanks got hit, first one, and then four at once. The blast echoed for a long time.

There was smoke everywhere. Everyone blazed away, but none of the Japanese planes were shot down. I guess it all lasted for a half-hour or less. Our fighters shot down some of the Japanese planes heading back to their carriers.”

Scheming an exit

“Then it was back to boredom. The Japanese never came back.”

Actually, the Japanese did come back, in a bad way, when they attacked Attu and occupied Kiska in 1942-43, two islands off the Alaskan panhandle. But Roald didn’t stick around the area long enough to join those battles.

“I figured I would just stay in Alaska until we won the war. Robinson had other plans. I liked Robinson. He was another odd duck. Robinson had an engineering degree from one of those California schools. Most of the other guys were what you’d expect; farmers, mechanics, factory workers and ne’er-do-wells who wound up in the California National Guard. But Robinson wanted to be an officer, and he changed my life. If not for Robinson, I might still be in Alaska.

“Robinson knew that enlisted guys stationed in combat zones could apply for officer training. With his engineering degree, he figured he was a cinch, and he said I should apply too. Not me, I wasn’t going to stick my nose out.”

The environment, the weather in Alaska, tried Roald’s patience. And sometimes, all a guy needs is a little impetus to change course.

“My big mouth finally changed my mind. Winter was back. The wind was screaming, and the chow was more rotten than usual that day. Outside the mess hall there were two barrels of hot water. You dipped your mess kit in the first barrel to knock off the food and grease. That barrel was usually half full of garbage by the time you got to it. The second barrel was the rinse barrel, but it was just as disgusting. Guys were always getting sick. I was out by the barrels, grousing to a buddy of mine, when I saw a G.I. come out of the mess hall. His mess kit was full of the slop he couldn’t eat.

“He slipped on the ice and the wind grabbed his garbage and blew it into my open mouth. I nearly threw up. That’s when I decided. I was getting out.

“An officer’s board called me down to Dutch Harbor for an interview. I knew I had to look my best. I dug out my dental bridge from the bottom of my barracks bag to fill the gap in my teeth. The damn thing didn’t fit because I hadn’t worn it for months. My speech was impaired. I said ‘One Fittfy Fife Howitzfer,’ and I sounded like a little baby. I dug further and pulled out a rumpled pair of woolies. Anything was better than the stained, stiff pants and ratty clothes we usually wore. I stuffed fresh cardboard into my shoes and walked to Dutch Harbor. The snowdrifts were huge, and I was sweating from the exercise. I arrived, thoroughly soaked and completely disgusted.

“The officers sat at a table. I had a chair out in front. They peppered me with questions, and they wanted straight, fast answers. I was getting nowhere until they asked me if I had any hobbies. Well, I kept my temper, and said that I liked to work with electrical equipment. ‘What, specifically?’ they asked.

“Now I was ready. I could have told them about the rat, just to be snotty, but I said, ‘Lie detector equipment.’

“‘Oh really?’ they said, ‘Show us on the blackboard.’

“I had given this speech several times in college in La Crosse [Wisconsin]. I started with the physiology, added the psychology, and finished with the electrical apparatus. They must have learned something. I got my orders the next week.

“Robinson was still there when I left.”

Onward and upward

“When I left the Aleutians, I traveled in style on a converted presidential liner called the U.S.A.T. Grant. The food was wonderful and there was plenty of fresh air.

“I wound up in Fort Lewis near Seattle, right on Puget Sound. I was a corporal by then, and awaiting assignment to Officer Candidate School. Some of the other guys there actually got civilian jobs before moving on to another assignment.”

Roald often said that Seattle was his favorite city.

“I applied for a job in the Officer’s Mess and worked as a waiter. There was no money in it, but I got all the food I wanted. I ate better than the officers did.

After serving breakfast, I would eat six eggs if I was hungry enough, and at dinner I would eat as much as I could stomach. I blew up like a balloon. My face was like a moon. I didn’t care. After the Aleutians, I never wanted to be hungry again. When I’d get some time off, I would go into Seattle to eat. I wanted vegetables so bad. I’d order a big salad and gobble it down. Being wartime, you couldn’t get good meat anywhere, but they had plenty of fresh fish in Seattle, so I ate that, too.”

Heading east

“Eventually I got orders to go to Fort Meyers in Virginia for officer school and artillery training. At officer school you get plenty of exercise, so I started to lose some weight. They also train you real well to keep things clean. One time I even took my whole bed down to the basement and cleaned it with a toothbrush. I was tired of getting demerits for dust on my bed.

“Fort Meyers is an old seacoast artillery base, across from the Navy base at Hampton Roads. In our artillery battery, we had guys from all over, some who had seen real combat. The equipment wasn’t anything special, except it was so old. They had a lot of 12-inch mortars, which could destroy anything in the harbor. They were pretty accurate, probably because they hadn’t been used much, and they lobbed huge chunks of ordinance. They taught us all the math and procedures related to artillery, and I didn’t have any problem with that. In August of ’43, I got my commission as a second lieutenant.”

Heading west

“I asked to be assigned back to Fort Lewis because a high school friend of mine from La Crosse lived out there. Forry Swann was his name, and he worked for Boeing. I had a few good weeks there, and Forry showed me around Seattle. Then there was some kind of crisis in the South Pacific – I think it was Guadalcanal – and the commander picked me and about half a dozen other lieutenants to send over there. The commander told me I was picked because of my “combat experience.” As if the Aleutians had prepared me for anything!

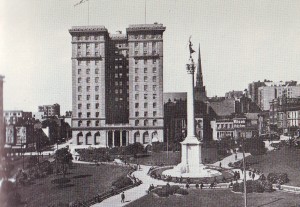

“We were sent down to San Francisco, and I bunked at the St. Francis Hotel right on Union Square. Soon after, they trucked us over to the port at Pittsburg, California, and we shipped out on the U.S.S. Chester. Now that was a ship! The Chester was a cruiser, capable of 30 knots and we made it to Hawaii in no time. We were on the shakedown cruise because the ship had just come out of drydock after some battle damage had been repaired.”

Heading south

“By the time we got to Hawaii, the crisis in the South Pacific was over. I was assigned to a coastal battery on the east side of Oahu. There was a Captain in charge who hadn’t had any leave since Pearl Harbor. When I arrived he left immediately to spend time with his family in Honolulu, so I was left in command for months. Just a green second lieutenant protecting the Hawaiian Territory.

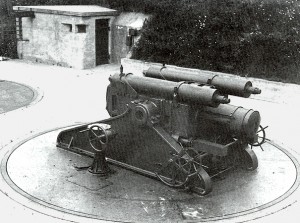

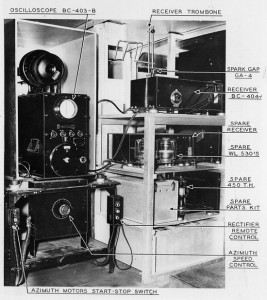

“We had two 7-inch guns off of a WWI cruiser. They were horribly inaccurate, and I had to rig up all kinds of special apparatus because the regular controls just couldn’t handle all the variation. The captain had the gun emplacements camouflaged to look like native huts or something.

“When the captain got back he scheduled a ‘live fire’ exercise and invited the brass to witness the whole thing. I was in charge of the plotting room, and the captain was commanding from up on the cliff. Our target was out in the ocean behind a towboat.

“When the first shots were fired, the shells landed way off target, and the huts collapsed over the guns and crews. The crews were struggling under fallen palm leaves and bamboo trying to load the shot and shell. The captain gave the order for the second salvo. The timing bell went off, and both gun crews shouted, ‘Relay number one!’ and ‘Relay number two!’ which is an artilleryman’s way of saying, ‘We’re not ready.’ When they finally were able to shoot, the shells landed all over the ocean.

“The captain shouted down to us, ‘You’re trailing too much on target!’ That meant we were shooting behind the target and not adjusting for its speed. So I threw in a correction that I thought would get us closer, and the crews managed to let loose another salvo. Those poor guys on the towboat must have thought they were done for. We nearly sank them. There was a lot of screaming and whining from the captain, but we were done for the day. It was just nuts.

“I finally left this Hawaiian paradise, all because of my big mouth again. The captain walked into the battery office one day and said, ‘What the hell is Ohm’s Law?’ Well, we had a first lieutenant by then, and he didn’t know, but I just piped up, ‘It’s I equals E over R, where I is the current in amperes, E is the electromagnetic force in volts, and R is the resistance in ohms. It applies to all electric circuits for both AC and DC current.” And then I went back to my work. The captain said, ‘Lieutenant Forseth, you’re going to radar school. Pack your bags.’

“Before I knew it, I was at the secret Navy radar school down at Pearl Harbor. It was easy duty; all the latest equipment and all the privileges of a Navy officer. It took me six months to become an artillery radar officer and then they assigned me to an Army battalion and I was shipped off to the South Pacific.

“If not for Ohm’s Law, I might still be in Hawaii.”

Island hopping

“Once onboard, I had to serve in rotation as Officer of the Day [O.D.] on the transport ship. Now, the skipper had a standing order that all men were to be below decks at night. I suppose he wanted to keep the decks clear in case of an emergency. Part of my job as O.D. was enforcing this order. It was an onerous order because as we got near the equator, the area below decks was steaming hot. And no one hated the heat worse than the guys in the Quartermaster Corps. They were all African-Americans. Their main job was to load and unload the ship. Not a very glamorous or easy job, and I suppose they resented not having equal rights to serve in all capacities. I would have felt the same way, but segregation was an official Army policy in those days.

“Their area below decks was as good as anyone’s. You might call it ‘separate, but equal’ accommodation. They objected to being ordered there every night though; they were sweaty enough already. Whenever I came along and ordered them below, they started chanting ‘Atabrine, Atrabrine, Atrabrine.’ They weren’t asking for Atabrine, the anti-malarial drug. They were making fun of the way it turned my skin yellow. Of course, their hue never changed, no matter what dose they took. I always felt worrisome as O.D. because we always had the same confrontation. There could be an insurrection, and I would be the first one thrown overboard.

“By the time I arrived in the South Pacific, MacArthur’s island-hopping campaign was well under way. Our guys were picking off all the strategic positions and leaving the rest to wither on the vine. At first they told us we were going to invade Yap, which is a tiny group of islands in the Carolines. Then, they decided to put that off, so they shipped us to the Navy base at Eniwetok Atoll. We had no shore leave, because there really wasn’t much of a shore there. We just lay at anchor for a month and a half, and baked in the sun. Eventually, we got in on the Leyte invasion, MacArthur’s return to the Philippines. That was no picnic.

“The Navy ‘softened up’ the landing beach on Leyte, a place called Tacloban. When we went ashore there was nothing left of that village except the tower of an old church. The cross was still up there. It was quite impressive. That was the only thing that survived, and it was probably an aiming point for all that shelling. I wonder if Tacloban is still there.

“The artillery pieces were all rejects; the good stuff was sent to Europe. We were definitely second string. We were using a new strategy for artillery support in the Pacific — our cannons would be brought to the beach in the second or third wave, when there was room to set them up. Mostly we would fire in support of the Army and Marines, but if there was a counter-invasion, we were responsible for coastal defense as well. That’s when the radar was important; to detect enemy ships and determine their bearing, distance, and speed.”

Random chaos

“American battleships had these huge 16-inch guns that fired shells weighing upwards of 2,000 pounds. Occasionally, one of those shells would land somewhere and fail to explode. They just got buried in the dirt when they’d land, and maybe other explosions would throw dirt and debris over the misfired shell, until it was all covered up or well hidden.

“A bunch of us in the Philippines were standing in a mess line to get some grub one day. A bulldozer nearby was leveling a field for an airstrip or something, and that bulldozer hit one of those unexploded, 16-inch shells that a battleship had fired who knows when. Well, that shell exploded with a wallop and a noise like you’ve never heard before. The whole area shook; the air and ground jumped like mad. The guy standing behind me had a tin cup in his hand, and a piece of shrapnel flew between us, shot that cup right out of his hand, and put a hole right through the cup. When he went to pick up the cup, it was smoldering from the hot shrapnel that tore through it. That shrapnel could’ve been a piece of the shell, or a piece of that bulldozer, or both. Man, that was a close call. But those are the kinds of crazy things that happened; just pure horror.

“This was at Base K, which was near Tacloban. The Seabees were building an airstrip for the Air Force, but they didn’t quite get done on time. During the Battle of Leyte Gulf, some of the Navy planes had to ditch and the pilots bailed out because the airfield wasn’t ready for them.”

Improvising the holidays

“People sometimes ask me, ‘What did you do on Thanksgiving that year?’ Or maybe it’s Christmas, or the Fourth of July, or my birthday. Heck, I don’t remember. All the days were pretty much the same. If you were in a battle, there was no time to celebrate. So celebrations occurred when you got the chance; when things calmed down, and the rations were more plentiful. Then you’d get platoon rations, with all the extra goodies, like cigarettes, coffee, tea and chocolate bars. That was our equivalent of a Thanksgiving dinner – chocolate bars.

“You have no idea how peaceful it is just to have a moment of rest. To be able to take a mess kit full of hot food, and sit on a river bank in the shade and enjoy a meal. You were so hungry that you just gobbled it down, but you enjoyed it just because the food was hot and you had a moment of peace.

“I do remember Christmas in ’44. We were at Leyte, and I was working to get guys moved off the transports and onto land. I had orders that allowed me to commandeer LSTs and get them out to the ships and bring them to shore where it was safer. The Japanese Kamikazes were in full force and hitting troop ships in the harbor.

“So, anyway, I had a lot of maps and charts and stuff, and was using crayons to color-code information. I started to get the idea that I would make a Christmas tree. So first I got a big old tent pole to use as the trunk. Then I started to cut up barbed wire to look like branches, and I used some tools from the radar outfit to drill holes in the trunk and screw on the barbed wire.

“I found some camouflage paint that I used to make the whole thing green. I got some small lights from trucks and other blown up stuff that was over at the motor pool. I also scavenged batteries from old Jeeps. They were 6-volt in those days. I used the crayons to color the lights red, green, and blue.

“When I got the whole thing done it looked pretty good, especially in dim light. I decided to donate the tree to the chaplain, and he set it up in the tent we used for the Christmas service. I guess it helped to make things a little better for the guys.”

More random chaos

“When we were transferring troops one day, we commandeered an LST and headed out of the harbor to rendezvous with a liberty ship. The ensign commanding was very young and he had a green crew. As we approached the liberty ship he started giving orders for engines and rudder, trying to lay alongside to transfer troops. Nothing happened; we just kept going, and one of those projecting booms on the LST collided with the side of the Liberty Ship and just sliced it wide open. The commander wound up in trouble, but I never heard exactly what happened to him.

“I later learned that, right about this time, a lot of the guys I knew at Fort Lewis were getting orders for Europe. Somebody figured out we didn’t need coastal artillery in Seattle anymore. What we needed was infantry commanders at the Battle of the Bulge. So they took all those guys from the rear echelon and sent them off to Europe. Few of them survived without at least getting wounded. It was a bloody mess.

“War is funny. It could have happened to me, but I had been sent out to the Pacific just because I had combat experience. Just because I had been up in the Aleutians, and shot at some Jap planes with my old Springfield rifle.”

A little R & R

“After Leyte, the rest of the Army went with MacArthur to Luzon. Our battalion was reassigned to the 5th Army and we shipped out on the U.S.S. Sea Barb for New Caledonia for rest and relaxation, and refit with new equipment. New Caledonia was high-class living; we had tents and cots and everything. We even played softball, but first we had to build a ball field.

“Some of the artillery pieces had tracked vehicles, which were their prime movers. These came equipped with bulldozer blades, so we used these to flatten down the hills. We also needed some trucks to haul dirt, and we found out that the Marines had plenty of old trucks we could salvage. They were pushing trucks off barges into the bay just because the brakes were shot! We grabbed some of these, fixed them up, and they worked just fine.

“The teams were organized by company. I was in the Headquarters Company, and we probably called our team something like ‘The Rockheads.’ Company A and Company B each had their teams, and we requisitioned bats and balls from Army supply. We had a swell pitcher on our team. He was from Madison, Wisconsin, and he could zip the ball so fast that nobody could hit it. Of course, he could throw curves and sliders and sinkers whenever he wanted to, but his fast ball just dominated the game. The other teams complained that his pitches were illegal, and we all had to defend his technique.

“The rest of us weren’t that good anyway. I played first base mostly, and it was a chore. The other infielders rarely threw the ball straight, so I was always getting pulled off the bag, and any dinky little hit would be a single. I wonder if there’s still a flat spot on New Caledonia where we carved out that ball field so many years ago.”

Weather radar

“I started using our radar to predict the weather. I could see the rain clouds on the radar and figure out their speed and direction. Then I’d call up the switchboard, and they would call around the island to the outposts and battery offices. I suppose they would send out runners to let people know what was coming. The radar was primitive in those days; a wavelength of 3 feet was great. But it was good enough for spotting thunderstorms, and ships could be easily seen.”

A scheme to ditch the crabby colonel

“I knew the battalion surgeon quite well. We were in the same tent, and had first met on Oahu, and were in the Leyte campaign together. He was an old timer and had been shipped to Hawaii a year before the war even started.

“The doc was a good guy.

“Our battalion commander was another story. He was only a lieutenant colonel, and had graduated from West Point with Ike. So he was bitter, thinking he should have been the Supreme Allied Commander. No one liked him.

“Doc cooked up a scheme just to get rid of him. He knew that the colonel had ‘Philippine Rot,’ so he scheduled physical exams for everyone in the Battalion. Somehow the colonel talked his way out of it and managed to stay. At least doc tried.”

Physician, heal thyself

“Doc and I got to talking one evening, and he mentioned that he was a wrestler in college. I said, ‘I can beat you.’ And he said, ‘No, you can’t.’

“So we stepped outside. We wanted room to maneuver, and we didn’t want to bust up cots or stuff. We went at it. The doc was good, but I knew alley fighting from my days in La Crosse. So I stepped on his foot and pushed him backwards. When he lost his balance, I still kept my foot on his, hoping he would twist his ankle. It worked, as usual, but his ankle broke.

“A broken ankle was as good as a million-dollar wound, and doc was scheduled to return to the mainland. How ironic; doc was heading home and the colonel was staying.

“I went to visit him in the hospital. I didn’t have to say I was sorry. I had done him a favor; he was heading home to his wife. He was so grateful that he gave me his pistol, a .45 Colt Model 1911. Pistols were a great prize because artillery officers all had carbines, and only the old timers had pistols. Of course, they taught us that the carbine was better than the pistol, and maybe it was. The .45 had tremendous knock down power, but you could get off a shot a little faster with the carbine. Now I had both.

“They taught us how to sling the carbine over the shoulder so you could get off a snap shot in any direction. When you’re slithering down some trail and looking for movement all around you, you’re always worried about what’s behind you. If you hear any little sound you want to be able to whip around and get off a shot. It was quite cute.”

Another boat ride

“As we bid the doc goodbye, he was smirking. We were on our way to another messy situation, and he was on his way home. They sent us to Ulithi. It’s another one of those atolls that the Navy used as a harbor.

“We went on another one of those troop transports. Better than the S.S. Cherokee, but still obnoxious. The food was always bad. For example, they had powdered potatoes for lunch and dinner every day. They were just a watery glob. In those humid conditions, food really didn’t smell good, and guys would lose their breakfast as they walked in for lunch.

“People were often seasick, so they would have garbage cans in the mess hall for guys to vomit in. The garbage cans were chained to the deck. In a heavy swell, they would slide all over, often with a G.I. wrapped around it, holding on with his arms and legs, just grateful for a handy place to heave.

“Those of us who weren’t prone to seasickness weren’t bothered at all. We would just sit there and eat, and watch people puke. I guess the Aleutians prepared me for that.”

The last campaign

“We weren’t in Ulithi long; they were marshaling forces for the Okinawa invasion. We were called in for the second or third landing. We had better equipment by then; the war in Europe was winding down. Okinawa was the last stop before Japan, and the Army was bringing in a lot of new equipment for the invasion of the main islands.

“That was the last campaign; Okinawa. It was savage. The landing was easy, but the going got rough as we moved inland. The Japs were well-dug-in, in caves in the mountains. The Marines fought for every inch and just kept pushing the Japs back bit by bit for almost three months. It all ended sadly.

“A lot of the island natives believed the Jap propaganda and killed themselves. Also, General Buckner was caught in an artillery barrage as he was visiting a forward observation post. He had been our commander back on the Aleutians. Ernie Pyle also died there, cut down by a machine gun. He was the best of the war correspondents and dressed like a soldier.”

Going home

“After things settled down on Okinawa and the island was pretty much occupied, I remember that the Army set up a radio station to entertain the troops. They broadcast from the Naha gravel pits and they were always having fun with the idea of a radio station in the pits. They only broadcast in the mornings.

I helped guys listen to radio by hooking up telephone wire from tent to tent, and I powered it all with our radar generator. We could put out 240 or 120 volts, and, of course, I sent 120 down the wires. The telephone wire had a lot of resistance to the current, but it worked OK, and no one got hurt. We also had quite a trading racket going, and sometimes I could trade radar tubes for light bulbs and things like that. We were always looking for a way to get civilized, you know.

“I was on Okinawa when the war ended: Aug. 14, 1945, a day I’ll never forget. How can you describe our joy? Every pilot on the island jumped into a plane and took off into the air. Totally free. Flying for fun. Spins and loops and twirls and buzzing every crowd they saw. Flying low over the ocean and kicking up spray from the prop wash. Flying up in the sky as high as they could go. They finally had to ground everybody. It was getting too dangerous. War is like that. One day it’s suicide missions, and the next day they’re telling you to be careful with your toys.

“Then we just waited. We knew we were headed home, but it’s hard to move so many millions. They set up an elaborate program to figure out who’d go home first. You know: Years of combat, whether you were married, whether they needed you for transport work, things like that. I got 97 points, but there were some officers with even higher scores, and they got to go home first. Other units wangled special treatment. I was once next in line to get travel orders when the Air Corps got priority for 10,000 men.

“We also had a commander, Colonel Wood, who was a louse and a mad dog. When the point system went into effect, every commander on the island rushed to get his officers and men sent home. Not the Mad Dog. He was afraid of losing his job! He was a West Point man and was very disgusted with us for wanting to leave the Army. He kept transferring us to different Army groups whenever our turn came to be de-activated. I was cussing a blue streak at everyone and everything. We even got transferred to the Replacement Center, which is the outfit that receives replacements from the States.

“We were all frustrated, but we survived, and I got back, eventually.”

Epilogue

Roald Forseth returned to his home state, Wisconsin, where he received a degree in physics in 1947. In his hometown, La Crosse, he met and married Patricia Eagan, fathered four children, and worked for Standard Oil his entire civilian career.

Roald died – one might say, “honorably discharged” – of natural causes on Oct. 18, 2006, age 86.

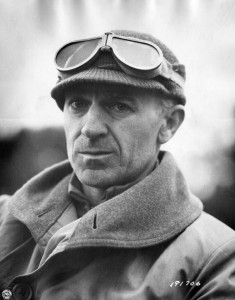

(Feature photo of Second Lieutenant Roald Forseth)

(Richard O’Hara contributed to this article.)

Mark Forseth is a regulatory technical writer with the Federal Aviation Administration in Seattle, Wash. His career has centered on public-broadcast journalism and technical writing for such industries as GE Medical; ABB Robotics; Harley-Davidson Motorcycles; Allen-Bradley Motion Controls; Johnson Controls; and Imago Scientific instruments, among others.