‘Raped Black Male’ talks survival in new memoir

Kenneth Rogers Jr. wants you to know he was raped.

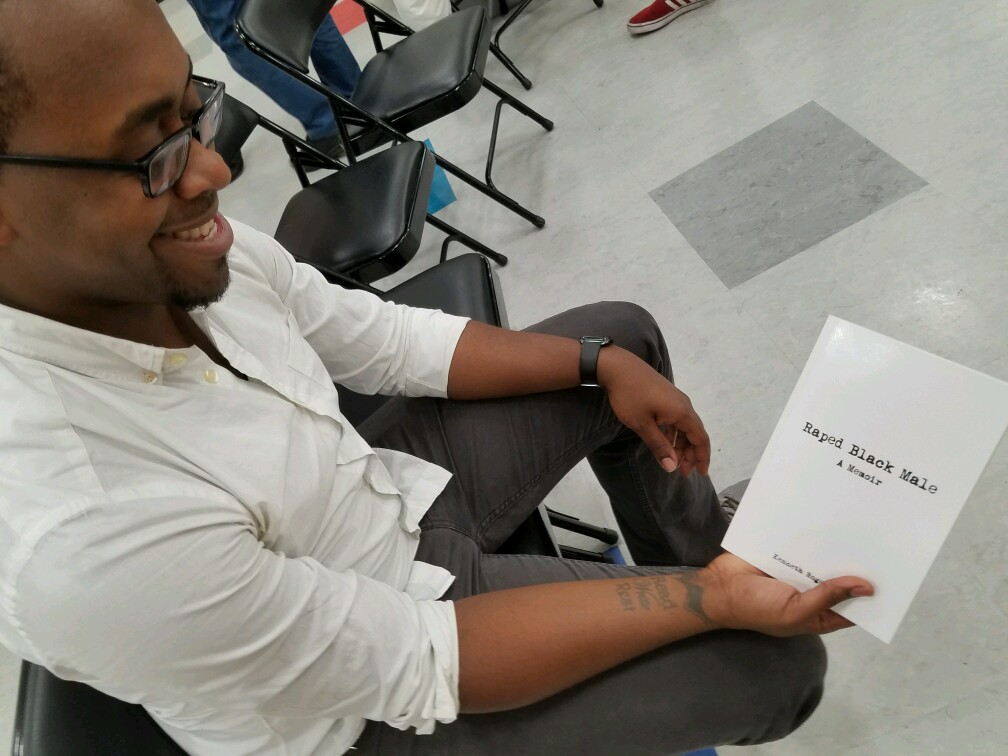

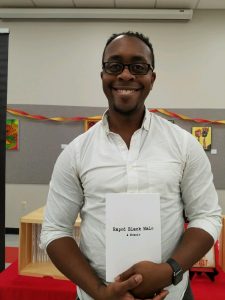

The 32-year-old science fiction writer’s work took an unexpected turn when he decided his sixth book, Raped Black Male would be a memoir about his darkest experiences of being sexually abused as a child.

The book traces his journey as a homeless man, fighting through depression and suicidal thoughts as he tries to come to terms of being raped. The book uses humor as well as his journals from years ago to weave a story of survival.

He claimed he was allegedly raped by his sister for two years, beginning when he was 8. The Baltimore Post-Examier was unable to reach his sister for comment. She was never charged in the incident. Rogers said she claims the incident happened only once, and that she confided that she was a victim of sexual abuse by a non-family member when she was a child.

While friends and family are usually perplexed when a survivor speaks out publicly as was the case with Rogers, social movements across the globe see these conversations as the first step to stopping sexual violence and helping survivors find support.

Rogers, who works with the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN) spoke about his healing process, his family, and helping others last month during a book signing at the Waverly Branch of the Baltimore Enoch Pratt Free Library. He lives in Baltimore and is the father of two girls and teaches Humanities at a middle school in Baltimore. His book can be purchased at Amazon.

BPE: Why did you write this book?

Rogers: I’ve been a writer for 10 years now and it wasn’t until recently that I came to terms with my sexual abuse as a child. The idea of writing about it seemed natural, because I always write.

When I go to therapy and when I get help there are no books for male survivors. The book that I used was actually for female survivors, so it made me think, I’m not the only one. There are other people like me who feel that they are by themselves, and they shouldn’t have to feel that way”

BPE: Did your family know about the abuse before you wrote Raped Black Male? How did they react to the book?

Rogers: They did not. I don’t use my sister’s name at all in the book purposefully. I wanted to tell my story. It wasn’t malicious in any way. I didn’t want to hurt anyone in the process. I told my sister and my parents what happened to me as a kid, and that I was going to write the book. My mom got a mixed story from my sister. She my sister that it happened once but not that had been going on for two years. My dad had no idea, and when he found out he told me to forget about it and not to talk about it anymore, which I did not, and he proceeded to not talk to me for nine months. Then he started texting me out of the blue. I texted him back and told him “I don’t want to talk to you until I get an apology.”

He texted back and said, “Your book called your sister a rapist, and its hurting.” He still hasn’t written an apology. I haven’t talked to him really. I haven’t talked to my sister since. My main support system has been my brother…and my mom has been there as well.

BPE: Do you think if had been a female family member who had been a survivor that your father would have reacted differently?

Rogers: I believe so. When I mentioned the fact that my sister had also been sexually abused, my dad said that if he had known he would have killed (the alleged rapist).

BPE: Do you talk to your sister?

Rogers: I do not, but it’s not just by my choice. I would love to talk to my sister. For a while I didn’t because I wasn’t ready, but I would probably be open to talking to her. She’s still my sister. We haven’t talked in about two years now. We stopped talking when I started having my breakdowns, when I started to go through some real mental struggles. The last time I talked to her I couldn’t get out of bed due to severe depression and anxiety. My mom probably told her to call and see what’s wrong. She said she hopes I get better. That was two years ago now.

Back when my brother left for college, we became close. That’s why it was so hard to write this. We were a normal brother and sister. Actually I stayed with her and her husband while I battled homelessness for two years in high school and when I took a year off from college. We had a good relationship, but as the years progressed and she didn’t get help for her sexual abuse either, so her life just kind of started to fall apart and I couldn’t be a part of that.

BPE: How does your sister’s own abuse relate to your story?

Rogers: Most perpetrators were abused themselves. It’s all about control. When someone who was abused sexually abuses someone else its almost like they’re getting back the control that they lost when the were abused. It continues over and over again until someone decides to put an end to it. There’s no doubt in my mind it’s all about the cyclic nature.

BPE: You said in the book that your empathy for your sister made it hard to hold her accountable. How did you reconcile those things?

Rogers: Holding people accountable has always been difficult for me. If I could take the blame, I would. But, in this case, I mean when I go to therapy and when I mediate I work to come to terms with fact that I didn’t do anything wrong.

For a while I felt like I can’t say anything bad about her because she’s my sister. But she raped me. But she’s my sister. The two ideas just didn’t match up. For the most part they still don’t. its still difficult for me. But eventually I came to terms with it that someone’s got to be accountable for what happened. I did nothing wrong. Three individuals who should be held accountable are my sister, my mom, and my dad.

BPE: Have they recognized that?

Rogers: My mom has. She beats herself up a lot, because she had no idea and it makes her really sick that could have happened in her own house. She’s talked to me about it and she’s trying to deal with it.

BPE: Do you hope your book is going to be a tool for people to use in therapy?

Rogers: I do, but I’m in the process of writing an actual guide for males that have been sexually abused as children. Its called Heroes, Villains, and Healing for Male Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse. Its about understanding abuse and recovery though superheroes. I use comic book archetypes- DC comic books- Batman, Superman, Flash, Aquaman, Green Lantern- to help people understand the different identities people take on as abusers and survivors.

I’m in the process of writing it now. Parts of it can actually be really fun.

BPE: How does being a survivor relate to masculinity?

Rogers: The idea that’s implanted in boys at a young age is that you should be stoic and not show your emotions. Because of this males are least likely to seek help for mental health problems. They are most likely to self medicate with alcohol and drugs, and sometimes if they can’t do that they kill themselves.

It’s the idea that this could never happen to a man. It makes them question “Am I still a man if that really happened to me? Am I still me?”

The idea of what makes a true man in our society is what stops many survivors from coming forward after they are sexually abused.

You gotta be strong, you gotta be tough, you gotta not cry. If you cry, that’s fagy, yo, you can’t do that.

And its ridiculous. It definitely is a hindrance to males in general, and females. If you don’t have a spouse who is able to actually express their emotions then you have a one sided relationship.

BPE: How does being a survivor relate to being black?

I don’t want to limit it to just black identity because there are so many survivors. When I was trying to come up with a title, I saw phrases like “aggressive black male” in the media. They were talking about black men being killed by police officers. Black men are shown as more vicious or more sexual, and I realized that those three words -raped black male- are never put together. Part of this book is about my identity.

BPE: Does your activism influence how your work as a teacher?

Rogers: Being a survivor has now become a part of my identity. A lot of people don’t want me to talk about it, and its detrimental. Especially to the 7th–grade students that I teach. That I cant just say “I’m a male survivor and I’ve written about it, and just let them know that If they are going through those things, I did and can help them.

My co-workers and my students know, but the school doesn’t want me to talk about it any more. They think the students are too young to talk about it. This happened to me when I was eight years old, so I know some of them could have experienced the same thing. And they wont say anything for another 20 years. Most men who have been abused don’t talk about it until 15 or 20 years after it happened.

At the beginning of the year I told my students, and all my parents, at back to school night, that I’ve written six books and that the latest one is about overcoming my sexual abuse. I got many handshakes from many parents, letting me know the courage that I had. Students wanted to read my book, they were interested, so I brought books in. Then I was called in to the administration and they asked me to not talk about sexual abuse.

And I battled with that for about two months. I experienced thoughts of suicide.

While on the other hand, there’s another high school, Patterson High School, that took my book and built a unit about this. They put it right next to Speak [by Laurie Halse Anderson] to get a male perspective and a female perspective. And they had me come and talk about my book and that was awesome.

BPE: Do you think that if when you were in middle school, if you had a teacher who addressed these issues, if it would have changed your recovery process?

Rogers: Most definitely. I would have said to myself, wait, this happened to other people. I would have a whole school of questions. Where can I get help? Is there something wrong with me? Because right now I think I’m eternally damned to hell. Can I still go to heaven? I just thought I was by myself.

BPE: Have you had any students or others reach out to you since you published?

Rogers: I did run into one of my former students. Completely happenstance. I was picking a cell phone for my wife for Christmas, and one of my old students came in, he used to be on my track team. I told him about my book, and he was like “that’s crazy because I just had a break down and was admitted to a hospital because I saw people in my family who abused me as a kid”.

This kid was awesome in school. He had a full ride to Johns Hopkins. He was on the fast track to become a doctor. After that happened everything went downhill. He was no longer able to go to classes or function. He dropped out of college. He’s trying to get back into college.

When I told him that happened to me, he was like “Oh my God! You were my teacher. I had no idea there were other people out there like me.” I could see it in his face that it helped that there is someone else he knows who relates. I gave him my number. He’s who I’m doing it for.”

Sarafina Harper studies English, Anthropology, and Gender and Women’s studies at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. She seeks to investigate current events using her anthropological background to reconcile the multitude of cultural lenses that shape our world. She understands the personal experience as inherently political and is an advocate for human rights. Sarafina is a poet and visual artist; her favorite canvases include every available wall, piece of furniture, or willing human being. She experiences live music as a spiritual sacrament and thrives where the freaks and artists wave their flags with pride.