Purple Hearts Reunited in Dublin to honor fallen Irish-American WWI hero

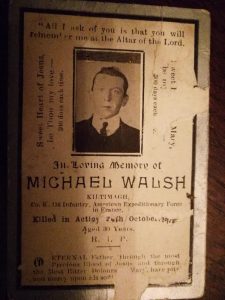

On 16 November 2018, the non-profit foundation Purple Hearts Reunited will conduct their first international ceremony in honor of WWI hero Private Michael Walsh. Private Walsh was killed in action on 24 October 1918 during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. This ceremony will conclude his family’s journey to honor their fallen hero as they receive his Purple Heart for the first time after 100 years.

This ceremony will occur in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, Ireland. The ceremony is open to the public and media.

Below, in Michael’s family’s own words, is his story and tribute:

From Claremorris to the Meuse Argonne: a Mayoman in the AEF 1918 by Finola O’Mahony.

3rd September 1911, my great uncle Michael Walsh of Claremorris Co Mayo arrived at Ellis Island, emigrating from rural Ireland, aged just 22 and like so many of his generation, in search of the American dream and a better life in New York. Attracted by the hustle and bustle of midtown, he found lodgings in a 4-storey tenement house, facing into the shadow of the 2nd Ave EL, boarding with the Irish-born Drennans and their slight, fair haired niece Jennie Holloway, arrived from Offaly two years before. Michael worked in the newly rebuilt, Grand Central Terminal as a platform man for the American Express freight agency. It was strenuous, but regular work, he earned union rates and sent money to his parents back home in Mayo. Life was full of promise.

6th April 1917, the USA entered the war on the side of the Allied forces against the Central Powers, led by the highly professional army of the German empire. The American Expeditionary forces (AEF) was created to deliver the massive manpower needed to overwhelm the enemy, dug in along the many hundreds of kilometers known as the Hindenburg line between the North sea and the Meuse river, East of France. In June 1917, Michael Walsh was drafted in New York, along with 24 million others across the US, between the age of 18 and 31. 2.7 million would be called up, to create the ‘citizen soldiery’ as General John Pershing named them, to reinforce the exhausted allied troops of France and Great Britain. Michael was one of approx. 500,000 emigrants from 46 countries who served their new country to fight a war that was not of their making, and never part of their American dream.

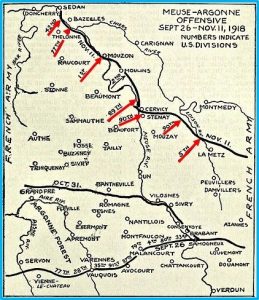

Inducted into the AEF in May 1918, Michael had about 3 weeks of training, before being assigned to Company K of the 116th regiment, 29th division, the Blues and Greys of the Virginia national guard. CO K sergeant McDaniel’s recalled ‘Most of these recruits were from New York city…there was not a man of the lot who knew enough about military life to do right face properly”, though he would later say that the new troops ‘progressed much better than was really expected of them’. On June 15th, they sailed on the US transport Finland, as part of a convoy of 13 ships of 70,000 doughboys. They landed in St Nazaire, Brittany and took the ’40 men, 8 horses’ French box car trains across France to the little villages of the Haute Marne, where they were greeted as heroes by the local inhabitants, according to the school teacher in Genevrieres who wrote in his war journal ‘these soldiers are notable for their drive, their discipline, and their sense of fun’. Michael’s last summer consisted of long night hikes, carrying their 40kg backpacks, and training in open battlefield fighting, in how to throw grenades, how to advance in assault waves, and how to quickly don their gas masks, to protect against the pervasive and deadly clouds of gas attacks. Michael’s unit was being saved for the final push, known as the Battle of the Meuse Argonne, which jumped off late on Sept 25th. Lasting 6 weeks, this battle would claim the lives of 26,000 Americans and nearly 100,000 wounded, more than any other US battle engagement anywhere, then or since.

Michael’s unit was assigned to the 3rd battalion, 58th brigade, alongside the French 18th division, with the objective of pushing the Prussian regiments back through some of the toughest terrain, the heights of the Meuse, where the enemy had all the best vantage points and would affect a vicious counter attack, prepared to fight man to man to hold their position.

Pvt Michael Walsh, inexperienced soldier, still managed to survive the nonstop fighting for a month, while around him his Co K comrades fell: their commanding officer Major Opie estimated they had been reduced to 1/3rd their original strength by mid-October.

24th October 2018, and our family group of nieces and nephews drives through the monumental gates of the Meuse-Argonne American cemetery, near Verdun France. Nothing prepares us for the sight of over 14,000 pristine, white marble crosses, crisply standing to attention in death, as they had paraded in life. Plot H, row 11, grave 9 and here it is, the final resting place of Private Michael Walsh, Co K, 116th Infantry, 29th Division, 100 years to the day he was killed in action. This is an emotional moment for my 90 year old mother Mai O’Mahony, and for her cousins Odran Branley, 87, from Brooklyn, Pat Walsh and his daughter Karen from Claremorris and brothers Billy & John Francis Walsh from Kiltimagh, as they visit this beautiful, tranquil, vast and lonely place, so often imagined and talked about at family gatherings over the years.

We retraced his path through Samogneux, Malbrouck hill, and across the killing field of Molleville farm, where many soldiers of the 116th regiment died. In the woods of Consenvoye and the Grand Montagne, we picked our way through the undulating German trench lines, which would in turn become the American reserve lines as they gained the advance. We saw machine gun nests, shell holes and corrugated German bunkers. Then we came across a large tin bucket, just sitting there where it had lain undisturbed for 100 years, riddled with bullet holes and with the side blown out, in a strange way, a small monument to the suffering of millions and to the grief of families like the Walshes.

Michael Walsh was in the front line with Co K on the 24th October 1918, as they pushed to capture an important observation tower near the Etrayes ridge. While no details were ever provided to his family, our archive research uncovered that Michael was hit by shrapnel at some point that day and was most likely the last member of his company to die, before they were pulled back from the front on the 27th October. His Irish luck had just run out.

The odyssey to France completed, there remains one final and important commemoration event for the Walsh family descendants, this coming Friday 16th November, in Glasnevin cemetery, Dublin.

Michael’s family never received details of his war experience and, while his parents received a pension from the US army, they never received the medals that Michael should have been awarded.

With the help of Purple Hearts Reunited, PVT Michael Walsh will finally be awarded the medals he so deserves. This will be the last of 100 medals the organization set out to return over the last two years to honor the centennial of World War I.

Purple Hearts Reunited has been working with the United States World War One Centennial Commission since February of 2016. The original Purple Heart, designated as the Badge of Military Merit, was established by George Washington – then the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army – by order from his Newburgh, New York headquarters on August 7, 1782. The Badge of Military Merit was only awarded to three Revolutionary War soldiers by Gen. George Washington himself. General Washington authorized his subordinate officers to issue Badges of Merit as appropriate. From then on, as its legend grew, so did its appearance. Although never abolished, the award of the badge was not proposed again officially until after World War I. General Douglas MacArthur, confidentially reopened work of a new design and by Executive Order of the President of the United States, the Purple Heart was revived on the 200th Anniversary of George Washington’s birth, out of respect to his memory and military achievements, by War Department General Order No. 3, dated February 22, 1932. Today, the Purple Heart is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the President to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after April 5, 1917.

An estimated 1.8 Million Purple Hearts have been awarded in our nation’s history. Today, in addition to being awarded to those who fight overseas, the Purple Heart is also given to military personnel who display bravery and valor as prisoners of war and while fighting certain types of domestic terrorist.

Purple Hearts Reunited is a nonprofit foundation that returns medals of valor to veterans or their families in order to honor their sacrifice to the nation. Since its beginning, the organization has returned over 500 lost medals, traveled over 100,000 miles, visited over 42 States, and has directly affected the lives of over 1 Million people. They were also recently highlighted on the popular History Channel TV show American Pickers.

CONTACTS PHR Founder, Zachariah Fike, 315-523-3609 or [email protected]