World War I Medal of Honor review urged for minority servicemen

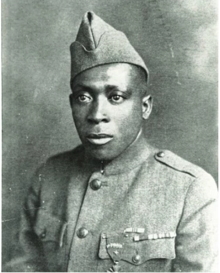

A group of decorated soldiers from the famed 369th “Harlem Hellfighters” proudly display the French Croix de guerre. Questions have long been raised as to why minority servicemen of World War I were bypassed in the awarding of valor medals, including the Medal of Honor.

WASHINGTON D.C. – For more than 100 years after the Union Army ostensibly secured the proposition that all men are created equal, Asians, Blacks, Latinos, Native Americans and, in many cases Jews, were routinely treated in American society as second-class citizens. “Separate but Equal” became bywords for institutional racism, while lines were created which few dared to cross. Even so, when called upon, minorities have served their country with distinction and honor. But muddying that favorable picture of military service are the racially-biased policies which were in effect during World War I. Not only did entire combat units remain segregated, but ethnicity appears to have affected the awards process — particularly as it relates to presenting the Medal of Honor.

The United States World War I Centennial Commission, and the George S. Robb Centre at Park University, are proposing a systematic review of the veterans potentially denied the Medal of Honor, in spite of valorous deeds during World War I. The review initially will center on African-Americans, but organizers say they intend to eventually include all minorities in the review.

A briefing by several members of the nascent task force was held Monday afternoon at the AUSA Anual Meeting at the at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center, Washington DC.

The briefing panel included:

– Dr. Gregory Gunderson, President, Park University

– Dr. Timothy Westcott, Director, George S. Robb Centre for the Study of the Great War at Park University

– Dr. Dwight Mears, historian, author of ‘The Medal of Honor‘

– Dr. Jeffrey T. Sammons, New York University, coauthor of ‘Harlem’s Rattlers and the Great War: The Undaunted 369th Regiment‘, and ‘The African American Quest for Equality’

After introductory remarks by Gunderson, Wescott spoke about the goal of the review.

“We have three outcomes in this review, from the center’s perspective. First, to collect a single, searchable digital database of the records of each respective military service member. Second, to write respective narratives of determined military service members to be submitted to appropriate agencies. And third, to provide appropriate agencies a digital database and consultation resource during the review process.

“We have undergraduate students who have already begun an initial review of African-Americans.”

(African-American servicemen’s records were chosen for the initial review because they alone were segregated as a group.)

Mears, the ‘The Medal of Honor’ historian, said he was surprised when he started researching the award, to find there wasn’t much scholarship on the medal since its inception during the Civil War.

“The early awards were authorized for almost any action in combat. To complicate the problem, there were no evidentiary standards. So the Army, in 1916, invalidated nearly 1,000 of the earlier medals.

“World War I ended up being the catalyst for the modern Medal of Honor. Because we were fighting alongside of allies who had more fully-fleshed out military decorations, Gen. Pershing, and by extension President Wilson, realized the lack of appropriate recognition could be a serious morale problem.

“The criteria at the time were race-neutral, but no African-Americans were recognized contemporaneous with the war. This was almost certainly a result of their ethnicity.”

Highlighting the distinguished service of African-Americans during WWI, author Sammons spoke about the commitment exercised by thousands of Black Americans.

“Approximately 40,000 out the 400,000 African-Americans in the United States Army served in combat during World War I. Out of that 40,000, not a single African-American was awarded a Medal of Honor either during the war or shortly thereafter – despite the fact that 70 received the Distinguished Service Cross, which is the nation’s second highest honor. We know that at least eight were nominated for the Medal of Honor, including one who was a native of Salisbury, Maryland.”

Simmons went on to briefly describe the extraordinary exploits of one William Butler, who saved his commanding officer, and his men, from a group of Germans who had infiltrated the Americans’ trench.

“My co-author and I believed that William Butler was deserving of Medal of Honor consideration before we knew that he had actually been nominated. We were working with a senator on getting a review of the Butler case, which unfortunately stalled. Then there was a decision made at some point, in consultation with Professor Westcott and President Gunderson, about expanding beyond William Butler.

“The two African-American recipients of the Medal of Honor from WWI (Freddy Sowers in 1991 and Henry Johnson in 2015) received the medal as part of a limited investigation.

“Sowers’ case was reviewed because his Medal of Honor nomination had not been processed. That investigation failed to aim at two other men from the 369th Regiment who had been nominated for the Medal of Honor, and also did not discover four others from the 370th who had been nominated.

“This points to the need for a serious, comprehensive, unbiased systematic review of valor medals – especially the Medal of Honor – for not only African-Americans soldiers. That will be the first step because remember, African-American soldiers were basically the only ones who were segregated by race. We know that some seventy received the Distinguished Service Cross. But we also know about the post-war disparagement and denigration of the role of African-Americans.

“There could be no greater testament to the courage and gallantry of the African-American soldier,” concluded Simmons, “than proper recognition of their accomplishments and sacrifice and service.”

Of the African-American servicemen who fought with the French, some 170 received the Croix de guerre. A review is also under way to determine if any of those men also received the Croix de guerre with Palms, the Légion d’honneur, or the Médaille militaire.

The proposed records review has been endorsed by both the VFW and the American Legion.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”