Frank Serpico: NYPD corruption buster

One Police Plaza is the headquarters of the New York Police Department (Wikipedia)

“My father said, never run when you’re right.”

“Good cops get the s**t end of the stick.”

“You’re either a freakin crook or you’re a cop.”

“You know how they got rid of informants? They gave them the cure; The cure was one-hundred percent pure [heroin] and no one would ever suspect anything.”

“If your partner gets shot, do you leave him there to bleed to death?” “Nobody volunteered to give me blood.”

Those are just a few excerpts taken from hours of conversations, spanning several days, that I had with Frank Serpico.

In this exclusive multi-part story, Frank Serpico recalled events that occurred during his lifetime, including his years on the New York City Police Department — some of which he has never talked about before. This story is about police corruption and it is not pretty. In fact, it’s dark, ugly and disturbing.

Payoffs, shakedowns, bribes, gambling, prostitution, narcotics, informants and murder. Put them all together and I could sit down and write a good novel about mobsters and organized crime.

This story is about criminals, except in this case the crooks carried a badge and wore the uniform of the New York City Police Department. What crooked cops have always failed to understand, or accept, even today, is that once they disgrace their badge by breaking the law, they are no longer cops — just criminals wearing a police uniform.

Bad cops, even today, turn their hatred toward others who exposed them, when they should focus that hate inward. They made their own choice to tarnish the badge and disgrace the police profession.

This is a story about one man’s frustrating five-year struggle in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s to combat corruption in the NYPD and the price he paid for being an honest cop. A lesson in a lone officer’s bravery to stand up for the oath he swore to when he became a police officer and on the other hand, a disgraceful lesson in police corruption that was so prevalent during that time that it permeated like a cancer through all ranks of the department.

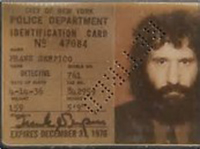

Francesco Vincent “Frank” Serpico was the first police officer in the history of the NYPD — and of any police department anywhere for that matter — to come forward and report and later testify about widespread systemic corruption. Serpico drove a bulldozer right through the NYPD’s Blue Wall of Silence. That wall, in effect makes police officers above the law; Then and now.

Today, the name Serpico is synonymous with honor and integrity when speaking about police work. But back then it was a different story.

In the NYPD, Frank Serpico was known at the time as a police officer who couldn’t be trusted because he had one major flaw; while working plainclothes, Serpico refused to go on the “pad,” that is organized corruption, taking payoff money while other officers were doing just that. That made him a marked man in the department.

What Frank Serpico did have, besides integrity, was brass balls and more intestinal fortitude than any man on the department at the time.

Back then, cops collected protection money from criminals, and in doing so insured those criminals that their activities could continue without the threat of being investigated and or arrested by the police. And it wasn’t only criminals who were targeted by the police. Shakedowns of business owners in the city was another avenue used by corrupt cops who believed that their badge entitled them to supplement their paycheck by engaging in criminal behavior.

Frank Serpico has been called a hippie cop, strange, weird, anti-establishment and a host of other names by police officers, then and now, on the NYPD. If remarks like that were meant to be derogatory and an attack on the man’s character, then it would be an honor to be called such names.

Frank Serpico has been criticized by both retired and active police officers because they felt that he should have done what he did differently. They believe that he had cast a dark shadow on the entire department and it put all cops, even the good cops, in a bad light. The answer to that is, there was no other way, and if the definition of a good cop is one who stands by on the sidelines and lets police corruption and misconduct flourish, then those cops are also part of the problem.

Frank Serpico’s perseverance and courage in combatting police corruption will always be admired and respected, not only now but forever in the annals of American law enforcement. As a former police officer, I say without any equivocation whatsoever that Frank Serpico is the quintessential role model to anyone who pins on a police badge.

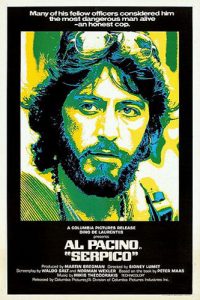

Some only know the name Frank Serpico because of the 1973 New York Times bestselling book, Serpico: The Cop Who Defied the System by author Peter Maas or the subsequent hit movie Serpico with Al Pacino in the title role. There was even a 1976 television series Serpico that starred David Birney.

What Happened

A US Army Veteran, Frank Serpico joined the New York City Police Department in September 1959 and remained on the force for a dozen years. All he ever wanted was to be a cop, and someday attain the gold shield of an NYPD detective.

For years, starting in 1966, Serpico tried to work within the NYPD structure to get the NYPD brass to act on his complaints of police corruption. His continued complaints fell on deaf ears, and he realized only then that there was nowhere else to go but outside the department.

An NYPD Captain once told him that if he pursued his complaints he would be put in front of a grand jury, after which he might well wind up face down in the East River. By this time, Serpico had met another cop, David Durk, who had connections in the New York City government.

In the spring of 1967 Serpico and Durk met with Arnold Fraiman, then head of the New York City Department of Investigation. Serpico told Fraiman about the pad and his unsuccessful attempts to get NYPD brass to act. Serpico would later testify that after giving Fraiman names, places and specifications about the corruption, Fraiman responded, “Well, what do you want me to do about it.”

That meeting with Fraiman was fruitless.

David Durk would later testify when he asked Fraiman why Serpico’s complaints were not being acted on, Fraiman told him he discounted Serpico’s information, saying that Serpico was a psycho.

Durk also took Serpico to meet with Jay Kriegel, a friend of Durk’s, who was then assistant for law enforcement to then Mayor John Lindsey. Again, no action. The mayor didn’t want to upset the NYPD apple cart by opening a can of worms.

Serpico was becoming even more frustrated by this time, even with his friend Durk, because the more people who knew about him, the more danger he was in on the streets. David Durk wasn’t working undercover on the streets. His job was pretty much a white-collar desk job. Durk had his ambitions of climbing higher on the NYPD ladder and the path to that was hanging onto Frank Serpico’s coat tails. Frank Serpico was the one who had first hand, direct knowledge of the corruption and Durk needed him.

While Durk was home at night with weekends off, it was Serpico’s life that was on the line day after day, night after night, working plainclothes with cops who did not trust him and who suspected that Serpico was talking.

Bronx District Attorney, Burton Roberts got involved. Roberts put some cases together against some dirty cops, but Serpico felt that was not enough. Serpico wanted the NYPD brass, the ones who knew about the corruption for years, were either part of it and or responsible for covering it up.

Things were getting even hotter for Serpico. He was in constant danger of losing his life, possibly at the hands of other cops. Nobody wanted to work with him.

The police didn’t have to kill Serpico outright, all they had to do was not be there at the one critical time when he needed help or assistance. If Serpico wound up dead, end of story.

Inspector Paul Delise partnered with Serpico on the streets. That’s what I said, a police inspector teaming up with a street cop.

Out of options and with nowhere to turn, in February 1970, Frank Serpico, Paul Delise and David Durk spoke with David Burnham of the New York Times. The Fourth Estate was Serpico’s last hope. On April 25, 1970, the headline in The New York Times read, Graft Paid to Police Here Said to Run into Millions.

The New York Times article reluctantly kickstarted Mayor John Lindsay to get off his butt and finally do something about police corruption. In May 1970, a commission was formed to investigate charges of widespread corruption in the NYPD, headed by former judge Whitman Knapp, forever known in history as The Knapp Commission.

In August 1970, Police Commissioner, Howard R. Leary, abruptly resigned, giving no reason and refusing to give a formal letter of resignation. Leary knew that the crap was about to hit the fan, and he did not want to be the captain on a sinking ship.

Patrick V. Murphy was named as the new Police Commissioner of the NYPD in October 1970.

With the formation of The Knapp Commission, Serpico was being accused by fellow police officers of working with the Commission. Serpico’s life at that time wasn’t worth a plugged nickel. Then he was transferred to Narcotics. Inspector Paul Delise told Serpico that he should be careful, that he could easily be set up.

On Feb. 3, 1971 at 10:00 pm when Frank Serpico walked into 778 Driggs Avenue in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, to move in on a drug dealer, he had no idea that his life would forever be changed.

According to prior published accounts, with two of his back-up officers standing within feet of him, Serpico, who spoke Spanish, approached apartment 3G, and knocked on the door as his partners told him to do. Just get the door open and leave the rest to us Serpico was told.

Serpico had his snub-nose .38 caliber in the ready. In Spanish he said, “I am a friend of Rodriguez, and want to make a buy.” When Edgar Echevarria, known as “Mambo,” opened the door, Serpico identified himself and tried to push his way in, but Echevarria slammed the door, jamming Serpico’s head, right shoulder and arm.

He asked for help from his back-up officers, no help came.

Serpico was shot in the face and got one shot off that hit Echevarria who then escaped out a window.

Serpico fell to the floor bleeding. Abandoned by his back-up officers, an elderly Hispanic man who lived in the building had called for help and stayed with Serpico until help arrived. You will hear more about the night Frank Serpico was shot, later, in his own words.

Echevarria would be caught several hours later.

What happened that day at 778 Driggs Avenue in Brooklyn some say was never properly investigated by the NYPD. With rampant corruption in the department at the time, there has always been speculation about the official version of what happened that night.

Less than a year before he was shot, Frank Serpico had testified against a police officer who was charged with perjury concerning that officer’s involvement with collecting protection money from gamblers. The officer was convicted and sent to prison.

Aftermath

Just how corrupt the NYPD was at the time was evident when later, both of his “back-up officers” were awarded medals for “saving” Serpico’s life. Apparently, the word back-up had a different meaning to the NYPD back then.

While Serpico was in the hospital, typical of the many get-well cards he received from fellow officers were: “With sincere sympathy, that you didn’t get your brains blown out you rat bastard.”

On May 3, 1971, New York Metro Magazine published an article written by Robert Daley, Portrait of an Honest Cop, Target for Attack. The front page showed an x-ray image of Serpico’s head with the caption, Circled area shows where .22 cal. bullet lodged in Officer Frank Serpico’s head. Not everybody was glad it didn’t kill him.

In the article, Daley wrote that a high-ranking police official stated that when word had come in that Serpico had been shot, that the building shook, because the NYPD was terrified that a cop had done it.

In May 1971 Frank Serpico was promoted to detective by Police Commissioner Patrick Murphy. Murphy never wanted to promote Serpico, but felt pressured because of the publicity surrounding him Why any police commissioner would feel that way towards the police officer who stood up for honesty and integrity and came forward, is beyond belief.

Murphy had been on the force for eighteen years before he was made police commissioner. During that time, he saw how widespread the corruption was, but he did not put his butt on the line, as Serpico had, to combat it. Murphy remained in the corner just like other NYPD cops who would later say that they never saw corruption.

If you were on the job during the 1960’s and early 1970’s and you never saw corruption in the NYPD, then you are either a freakin’ liar or had your head buried so far in the dirt that you didn’t see what was going on all around you.

Adding insult to injury Serpico was not promoted to detective first grade. In the second part of this story you will hear what Frank Serpico has to say about that.

Serpico was also awarded the NYPD Medal of Honor, along with his detective’s shield. With no ceremony, he was handed both the Medal of Honor and his shield like it was a “pack of cigarettes,” Serpico said.

Serpico told me, “Yes, no ceremony. Never gave me my certificate, until a couple of years ago. I kept asking each new administration for my Medal of Honor certificate. When Ray Kelly became commissioner, I asked again. They said come into the commissioner’s office to pick it up. Sensing they were planning a news photo-op, I said put it in the mail. When I opened the envelope, it was my certificate of promotion to detective, signed by Commissioner Ray Kelly, dated 5/1/71. No Medal of Honor certificate.” Serpico said, “in 1971 Patrick V. Murphy was the police commissioner. They call themselves professional?”

On May 10, 1971 Serpico testified at the departmental trial of an NYPD lieutenant who was accused of taking bribes.

In August 1971 Inspector Paul Delise, who had partnered with Serpico on the street, was promoted to Deputy Chief Inspector. Delise told the New York Times at the time, “It’s very difficult to come down on a policeman who has risked his life with you. However, it is the job. We have taken an oath to uphold the law. Our job is to fight crime, and corruption is criminal.”

In October 1971, Frank Serpico testified at the Knapp Commission amid a bevy of television cameras and news microphones. Former U.S. Attorney, Ramsey Clark offered Serpico his legal services pro bono. Serpico’s opening statement to the Knapp Commission was a ground-breaking moment in American law enforcement:

“Through my appearance here today … I hope that police officers in the future will not experience … the same frustration and anxiety that I was subjected to … for the past five years at the hands of my superiors… because of my attempt to report corruption. I was made to feel that I had burdened them with an unwanted task. The problem is that the atmosphere does not yet exist in which an honest police officer can act … without fear of ridicule or reprisal from fellow officers …

“We create an atmosphere in which the honest officer fears the dishonest officer, and not the other way around. Police corruption cannot exist unless it is at least tolerated… at higher levels in the department. Therefore, the most important result that can come from these hearings … is a conviction by police officers that the department will change. In order to ensure this … an independent, permanent investigative body … dealing with police corruption, like this commission, is essential …”

Both in October and December of 1971, Frank Serpico gave hours upon hours of testimony to the Knapp Commission. He gave a blow-by-blow account of his five-year struggle to get the NYPD to act. He named the superiors in the department who he had gone to, he told the Commission of his meetings with Arnold Fraiman, head of the Department of Investigations and Jay Kriegel from the Mayor’s office.

Throughout its two-and a-half-year investigation other NYPD cops would testify in front of the Knapp Commission. Some were honest, some were corrupt cops who were only interested in keeping their crooked butts out of prison and were backed into a corner. One corrupt NYPD cop who testified, William Phillips, was later convicted of a double murder and sent to prison.

The Feds got involved, investigating corruption far beyond just the NYPD, at all levels of the criminal justice system in New York City.

Make no mistake about it, Frank Serpico’s actions started it all. What he did was pack the snowball that rolled over the NYPD like a bad dream.

On May 31, 1972, Edgar Echevarria, the drug dealer that had shot Serpico in the head, was convicted of attempted murder. Serpico had testified at the trial.

On June 15, 1972, Serpico retired on a medical disability from the NYPD.

Along with his sheepdog Alfie, Serpico moved to Europe, where he lived in Switzerland and then in the Netherlands. He traveled and studied throughout Europe.

The Knapp Commission Report

On December 29, 1972, after a two-and-a-half-year investigation, the Knapp Commission released its 283-page final report. It was the biggest scandal ever to hit the New York City Police Department at the time. The corruption was unprecedented.

“The rookie who comes into the Department is faced with the situation where it is easier for him to become corrupt than to remain honest, wrote the Commission.

The Commission estimated that as many as half of the 30,000 NYPD officers at the time were involved in corruption in one form or another, and those that weren’t directly involved in corruption, knew about it and remained silent. The Commission described corrupt cops as falling into two categories, meat eaters and grass eaters. Meat eaters are cops who aggressively misuse their badge for personal gain. Grass eaters accept the payoffs that the happenstances of police throw their way.

As far as the plainclothesmen assigned to enforcing gambling laws, the Commission found, “a strikingly standardized pattern of corruption,” and that they had collected regular and bi-weekly payments amounting to as much as $3,500 from each of the gambling establishments in their jurisdiction.

The Commission found that corruption in narcotics enforcement lacked the organization of the gambling pads, but the “scores” were common and the amounts staggering.

Narcotics officers were involved in shakedowns of narcotics dealers; theft of seized money and narcotics; possession and sale of narcotics; receiving stolen property; “Flaking,” or planting narcotics on an arrested person; “padding,” or adding to the quantity of narcotics found on an arrested person; storing narcotics, needles and other drug paraphernalia in police lockers; illegal wiretaps used in either making cases or to blackmail suspects; purporting to guarantee freedom from police wiretaps for a monthly service charge; selling official information; Accepting money for registering as police informants’ persons who in fact were giving no information, and falsely attributing leads and arrests to them, so that their “cooperation” with the police may win them amnesty for prior misconduct, financing heroin transactions; testing the purity and strength of unfamiliar drugs on addict-informants; introducing potential customers to narcotics pushers; revealing the identity of government informants to narcotics criminals; kidnapping critical witnesses at the time of trial to prevent them from testifying; providing armed protection for narcotics dealers; offering to obtain “hit men” to kill potential witnesses.

Detectives assigned to general investigative duties conducted shakedowns of targets of opportunity, amounts reaching several thousand dollars.

Uniformed patrolmen assigned to street duties were receiving money on a large scale but with smaller amounts. Those assigned to radio cars also participated in gambling pads and received regular payments from construction sites, bars, grocery stores and other businesses.

Superior officers who were corrupt would use patrolmen as their “bagmen.”

The Knapp Commission stated that although First Deputy Police Commissioner, John Walsh who headed the NYPD’s anti-corruption squad, Commissioner Arnold Fraiman of the New York City Department of Investigation, and Jay Kriegel of the Mayor’s office, all acknowledged the extreme seriousness of the charges and the unique opportunity provided by the fact that a police officer was making them, none of them took any action.

No general evaluation of the problems of corruption in the Department was undertaken until The New York Times publicized the charges, the Commission wrote, and that it was clear that the Mayor’s office did not see to it that the specific charges made by Frank Serpico were investigated.

Former Assistant Chief Inspector, Sidney C. Cooper stated at the time, “Not very long ago we talked about corruption with all the enthusiasm of a group of little old ladies talking about venereal disease. Now there is a little more open discussion about combatting graft as if it were a public health problem.”

The Village Voice at the time wrote, “There is no more talk of a few rotten apples in the barrel. It is the barrel that is rotten.”

Serpico Now

Frank Serpico, now 81 years old, returned to the United States in 1980. He resides in Upstate New York.

For over 45 years he has been living with injuries sustained from the shooting. He is deaf in one ear, walks with a limp and still has fragments of the bullet that entered his face, lodged near his brain.

Over the years, Frank Serpico has lectured at universities, colleges and police academies. He is an outspoken voice against police corruption, brutality and misconduct and what he contends is the dwindling of civil rights. He supports “whistleblowers,” whom he calls “lamplighters,” after Paul Revere who was responsible for having lamps lit to warn of the coming of the British.

The following was posted online by a young woman a few years ago:

“I grew up with a grandfather who was one of the dirty cops that Serpico worked with. I continuously heard stories about how he was a “rat bastard”. To this day that term continues to sicken me. How it is that my grandfather turned Serpico into the bad guy is beyond me … I’m not sure all that went on with the Knapp Commission but I do know that many cops including my grandfather got wind of it before everything struck and he was one of the many who was able to retire early without so much as even a scratch on him. My grandfather may have considered Serpico a “rat bastard” but I will always consider him a hero. Kudos Mr. Serpico for not only risking your life to do the right thing, but continuing to speak out against police corruption. You will always be a hero in my mind and a source of inspiration. Thank you for giving so much of yourself … Thank you Frank Serpico, for paving the way.”

On May 24, 2010 Frank Serpico gave the opening remarks at the National Whistleblower Assembly. It is the most remarkable speech that I have ever heard concerning corruption and ethics. This speech should be mandatory listening in every police academy, every board room and every political office in the country. It is pure Frank Serpico and it’s the essence of what this man is all about.

The first few opening lines are as follows:

These are indeed troubling times that require us to speak up for our principles. Time and again when I talk to people about corruption invariably the response I get is, it’s human nature, and in so doing we justify its existence and conveniently absolve ourselves of any further responsibility. I do not believe that corruption or ineptitude are natural functions of the human spirit, however, I do believe that a small group of individuals, with egos and greed far greater than the title or office they hold, often take advantage of their position to enrich themselves and exploit the very people that they are meant to serve. To put it bluntly, positions of leadership and trust often equate a license to steal or otherwise behave unjustly or immorally. Titles themselves do not necessarily assure us, as they should, of the credibility or the integrity of the holder. Whether the title be president, CEO, police chief, bishop, justice of the court, etc. Against all these impressive titles there is or has been documented evidence of improprieties and then some. Unfortunately, because of the power of the office those that occupy these positions feel they are immune to scrutiny and prosecution, untouchable, too big to fail, too big to go to jail. Some may find this difficult to accept, not wanting to believe we are vulnerable at the hands we trust. But having been on the receiving end of the abuse of power, I’m all too familiar with this bitter truth. In the old days, men like Willie Sutton were called bank robbers, their pictures hung in the post office for stealing from local banks. Today, individuals who defraud us of mega-millions have their pictures hanging in board rooms…

A new documentary Frank Serpico directed by Antonio D’Ambrosio premiered this past April at the Tribeca Film Festival. The documentary is now an official Sundance select at the Sundance Film Festival. He also has an upcoming book, It’s All A Lie about his time in the NYPD and his life.

Over the years, many people have written books mentioning Frank Serpico and events that occurred at the time on the NYPD. Some of these authors have distorted the facts and/or attempted to undermine Serpico’s reputation.

I have always wanted to talk to Frank Serpico. Not only because I have admired him, but I have heard so many different stories over the years about him and what life in the NYPD was like. Too many books read, too many ex-NYPD cops spoken to, and way too many conflicting accounts.

The conversations I had with Frank Serpico were candid and blunt. You will hear from Frank Serpico in the forthcoming second part of this compelling story.

Doug authored over 135 articles on the October 1, 2017, Las Vegas Massacre, more than any other single journalist in the country. He investigates stories on corruption, law enforcement, and crime. Doug is a US Army Military Police Veteran, former police officer, deputy sheriff, and criminal investigator. Doug spent 20 years in the hotel/casino industry as an investigator and then as Director of Security and Surveillance. He also spent a short time with the US Dept. of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration. In 1986 Doug was awarded Criminal Investigator of the Year by the Loudoun County Sheriff’s Office in Virginia for his undercover work in narcotics enforcement. In 1991 and 1992 Doug testified in court that a sheriff’s office official and the county prosecutor withheld exculpatory evidence during the 1988 trial of a man accused of the attempted murder of his wife. Doug’s testimony led to a judge’s decision to order the release of the man from prison in 1992 and awarded him a new trial, in which he was later acquitted. As a result of Doug breaking the police “blue wall of silence,” he was fired by the county sheriff. His story was featured on Inside Edition, Current Affair and CBS News’ “Street Stories with Ed Bradley”. In 1992 after losing his job, at the request of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Doug infiltrated a group of men who were plotting the kidnapping of a Dupont fortune heir and his wife. Doug has been a guest on national television and radio programs speaking on the stories he now writes as an investigative journalist. Catch Doug’s Podcast: @dougpoppa1

First of all, I know there ‘are’ good cops. Just as there are good lawyers, presidents, doctors and politicians. That being said, thank you for this more recent, illuminating article on Serpico. I just watched the D’Ambrosio’s documentary and posted my admiration for this courageous whistleblower on an Italian-American internet thread. Most responses were positive, but one was in ‘flaming’ font and full of the old ‘rat bastard’ rhetoric. I was told to: ‘MIND MY OWN BUSINESS in no uncertain terms. After reading more details of the Knapp Commission, revealing the breadth and scope of the corruption, I maintain my admiration for this man.