Travels in New Mexico: Up At Ancient Way

Our love affair with the stunning region of New Mexico along the highway known to history as the Ancient Way – officially it’s New Mexico Route 53 – began five years ago, and it grows deeper as time passes.

My partner, the artist/photograher Ray Petersen, and I had been on a visit to the Navajo Reservation, and staying at Good Shepherd, an old Episcopal mission at Fort Defiance, Arizona.

It had been a great visit. Our friend, the Navajo artist Sheldon Harvey, had given us a detailed and intimate tour of the Navajo Nation – Monument Valley, Canyon de Chelly and Spider Rock, his hometown of Lukachukai, and much else. We had a lot to think about.

When he saw us preparing to leave, the caretaker at Good Shepherd came by and asked, “Have you guys been to the Ancient Way Café?”

“No,” we said, adding that we hadn’t even heard of the place.

“You should stop there. It’s a fantastic place and you’ll like it. The food is great, really great, and its run by a bunch of guys from San Francisco.”

Stop we did – it was on our way back to Albuquerque – and we’ve been returning ever since. The food was indeed fantastic, and alone was worth the stop. But it’s not just the food that brings us back, and not just the friendly and interesting staff.

What the Good Mission caretaker failed to mention (and probably didn’t think he needed to) is that the café is right smack in the middle of one of New Mexico’s most scenic regions, an area that includes, within reasonable distances of one another, such varied wonders as El Morro Valley (where the café’s located), El Malpais (“the badlands,” pronounced el-mal-pie-EES, an enormous area of lava flow and extinct volcanoes), and the pinon- and ponderosa-pine covered Zuni Mountains.

I should mention that New Mexico is quite a change for Ray and me. Most of the year we live in a small town in green and oh-so-humid coastal Delaware, near the Atlantic Ocean. But for the past four years, we’ve had a condo in downtown Albuquerque, New Mexico’s largest city and a perfect place from which to see the rest of the state.

On most days of the year the New Mexico sky is intensely blue and often cloudless, and the bright sunlight renders everything in the often very dramatic landscapes visible down to the finest detail. Sunrises and sunsets are almost always stunning. And I believe we’ve seen more double rainbows (particularly gorgeous when seen up against high mountains) in New Mexico than anyplace else we’ve been.

And we like New Mexico’s unique blend – Native Americans, Hispanics, and “Anglos” (a catch-all word for everyone else) – and of people who have lived there for many generations and of newcomers. It’s a mix of the traditional and the recent, and it makes New Mexico seem at the same time very ancient and very new.

On one count, the caretaker at Good Shepherd Mission was wrong: we found that Ancient Way Café isn’t run by a “bunch of guys from San Francisco,” though they might have been.

They’re actually from all over America. Maqui, who may be the one you talk to on the phone if you call ahead for reservations at the cafe, comes from Detroit. Standing Feather – our waiter on our first visit, dressed in an elegant sarong – left Salt Lake City and came to New Mexico. Red Wulf (his full name is Red Wulf Standing Bare/Bear) grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania.

These guys cook, bake, wait tables, and much else, including raising fresh vegetables and herbs in the summer. There are two cooks, Nova – who describes herself as having lived “in Alabama and many other places” – runs the kitchen in the early part of the week and Lamont, a Native American who is chef later in the week. Lamont’s infectious laughter bubbling from the kitchen is a joy to experience. It makes you feel good about everything.

Sharon is another regular. She’s Ancient Way Café’s practical-minded owner who could not believe Ray on our last visit when he told we were up their so he could photograph a mistletoe that grows on the one-seed junipers in the area. “You’re pulling my leg,” she said.

She thought we were up there to hunt elk, like many of her guests do. But Ray wasn’t pulling her leg: One of his goals on the visit was to photograph the mistletoe, so he would have images to work from to do a painting of the plant that’s to be in a show in June, 2013, to which he’d won an entry.

The Café

Ancient Way Café is a rustic, Western-style place made of wood, with a wide front porch where you can dine, weather permitting. The restaurant inside is small with a pot-bellied stove and with walls and shelves filled with local art – including ceramics by Maqui, Standing Feather’s paintings, and much else.

The café takes its name from the road known as “the Ancient Way” and the road is ancient, at least by American standards. For more than a thousand years it’s been the trade route that connects two of the oldest communities in America, the Zuni Pueblo and the Acoma Pueblo, both of which had been flourishing towns long before the Spanish arrived in Mexico or the English in Virginia.

Not surprisingly, the café’s menu reflects the region and is influenced by Indian, Hispanic, and New Mexico ways of cooking.

What to eat?

Everything we’ve had at Ancient Way’s been good and much of it very good.

Their pies are superb. I particularly like their blend of apple, green chiles, and pinon nuts in a single, tasty mix. On our visit late this past fall, on a day following an eight-inch snow fall at Ancient Way, Ray had chicken cacciatore (made by Red Wulf) that Ray described as “the best I’ve ever had.”

I had a Reuben sandwich that I could say the same thing about. I’m also very fond of the French toast that’s on the breakfast menu.

If you come upon the café driving east on Route 53, you’ll encounter a road sign put up by someone with a sense of humor (surely a local) warning “Congested Area Ahead.” Don’t be alarmed. The congested area consists of four buildings that constitute what’s known as “El Morro Village.”

The four buildings are the café, and to its right and to the east, Inscription Rock Trading & Coffee Company, a coffee bar and a place to buy works by Navajo and Zuni artists and a place too where live music.

Across Route 53, there’s El Morro Feed & Seed and an old school building (built in 1948) that now serves as an art gallery and community center. You can’t miss it: it’s painted bright red, and blue, and yellow. There’s often a show by local artists on display – ceramics, paintings, sculpture, quilts, and more – and sometimes locals put on plays (“The Gin Game” was featured this Fall). For the Old School Gallery’s doings, click here.

This “congested area” may not seem like much but it is the visible representation of a much larger community of artists, nonconformists, poets, and other highly individualistic people (I’ve heard some of them call themselves “homesteaders”, an allusion to the Old West) who have chosen to make El Morro Valley their home and live alongside the Hispanic, Navajo, and Anglo ranchers, and other residents who have lived there for generations (or in the case of the Acoma and Zuni puebloans, thousands of years).

It’s an impressive community that’s coming into being in El Morro Valley among the homesteaders and locals. Clearly it is a way of life that is at least partly based on rejection of modern America’s hustle and bustle, of modern American materialism and the hollowness which many find in the soul of city life.

But I think it’s wrong to see the homesteaders and nonconformists of El Morrow Valley as living lives based solely based on rejection. That’s too negative by far for what’s happening there. As I see it what’s happening is positive, and often deeply moving.

Much of what is taking place and coming into being springs from the very human desire to live where you’d really like to live and raise your children there. It is a very American thing, this move to a new place to create a new life. It’s as old as the Pilgrims who came to the New World to worship as they saw fit. And it’s as recent as the men and women from small towns who flocked to Greenwich Village in the early 20th century, or to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s.

Indeed the present day homesteaders aren’t the first nonconformists to come to El Morro Valley. In the second half of the 19th century Mormons settled the town of Ramah (current pop. 407), which is today looks like the Old West, something like you’ve seen in the better Western movies.

What’s happening in the valley these days also has a great deal to do with Indian spirituality. Standing Feather, Red Wulf, and Maqui, of course, had their Anglo names, which they’ve shed for the ones they have now, and their lives are deeply spiritual. At Ancient Way they offer healing sessions based on Indian spirituality and on other traditions.

They have an Indian inspired sweat lodge which they use as the spirit directs them, and they have drumming sessions. Check out the YouTube, “Standing Feather and Red Wulf” that features the two of them being interviewed in the woods behind the café and talking about the spiritual life available to them in El Morro Valley.

Another influence on the homesteaders is the Radical Faerie Movement, a loose-knit and highly individualistic group that’s been around since the 1970s. The Radical Faeries are into festivity and the celebration of life, and are themselves influenced by Native American spirituality and ritual. The Faeries have a sanctuary in the Zuni Mountains.

Another group that’s representative of El Morro Valley is the Zuni Mountain poets, who meet Sunday mornings at Inscription Rock Trading & Coffee Company. The group has recently published an anthology of their poems, entitled “The Zuni Mountain Poets”, available at the Schoolhouse Gallery. It includes works by Standing Feather and Red Wulf, among others.

Several websites offer information about the spiritual, cultural, and artistic life in the area. The Enchanted Lands website offers a comprehensive look at “Living Along the Ancient Way in El Morro Valley, New Mexico,” as the website puts it and describes life at Ancient Way romantically: “El Morro Valley. . .Where Dreams Take Wing & Fly.” In addition, The husband/wife teach of Ethel Mortenson Davis and Thomas Davis, members of the Zuni Mountain Poets, have a marvelous website that provides regular updates of life in the valley through poems and pictures.

When we’re up at Ancient Way these days we rent one of the rustic cabins available in the area behind the café (there’s also a yurt and spaces for RV camping and regular camping). Our rescue dog Pearl – half Rhodesian ridgeback, half pit bull with an alpha, take-charge personality – joins us; she loves New Mexico as much as we do, probably more. Her off-leash possibilities are far wider than they are in Delaware, and Delaware offers far fewer forests, critters, and wide-open spaces to experience.

Do not miss the nights when you’re up at Ancient Way. The silence then can be so palpable that you think you can hear it (for those accustomed to urban life, the silence takes getting used to). And you will marvel at the number of starts and the density of the Milky Way. It’s the sort of view at night our ancient ancestors saw every clear night, and no doubt aroused feelings of awe and wonder in them, just as they do in us.

Here’s the things we see when we’re up at Ancient Way.

El Morro National Monument

You’ll see “El Morro” translated from the Spanish most often as “the headland” and sometimes more awkwardly as “a large isolated rock.” Both are accurate. But my favorite explanation of its meaning is that it comes from “morra”, which means “crown of the head” in Basque, a language spoken in northeast Spain.

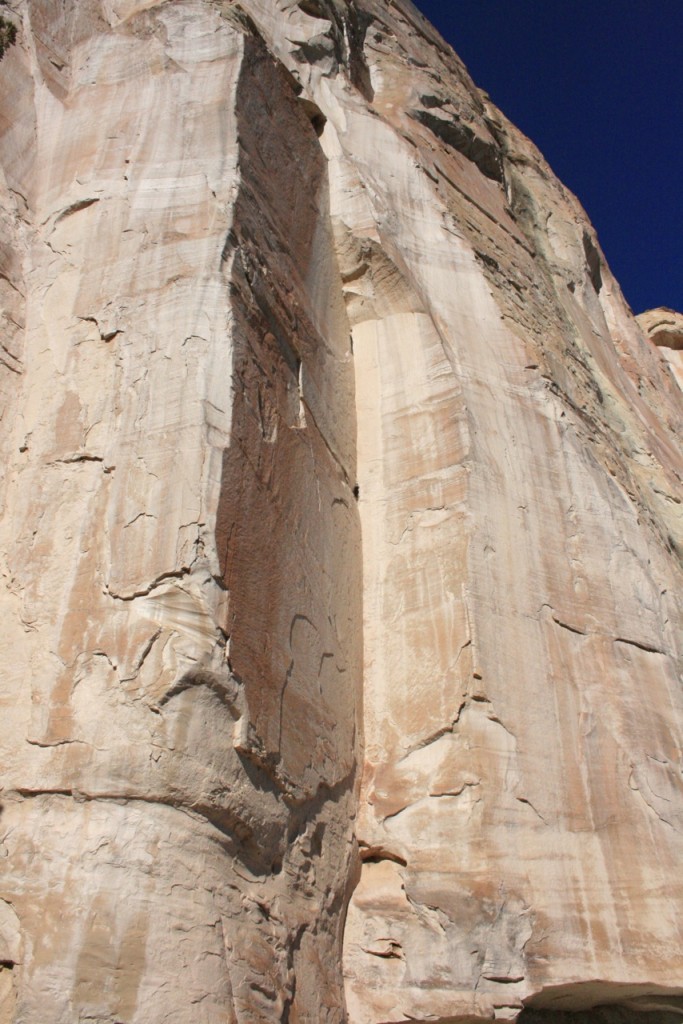

Whatever the translation, El Morro is a 200-foot-high cuesta, a ridge that rises from the valley floor gradually until it reaches a precipitous edge that falls almost in a straight line back down to the valley. The view from the top is spectacular – there’s no better view of the whole of El Morro Valley.

El Morro National Monument is federal property, so there are helpful rangers available and excellent trails that take you to the top of El Morro and anywhere else you might want to go in the park. And if you take the steep climb to the top, you’ll learn that the splendid view isn’t the only reason to do the climb.

On top of El Morro, there is an ancient pueblo village – the people who lived there are called the Anasazi, after the Navajo for “ancient ones” – that was abandoned around the year 1400, after about a century of existence. Atits peak, the town had between 1,000 and 1,500 inhabitants living in about 875 interconnecting rooms. Today, visitors can see several of the apartments excavated and gain an idea about how the Anasazi lived, how they collected water, and where they performed their rituals. I believe rituals done atop El Morro near the sky and with the view of the valley below would have been very intensely experienced.

The Anasazi were very likely the ancestors of present day Zuni, and the Zuni name for the village on top of the cuesta is “Atsinna,” which means “the place of writing on the rocks”, a definition that brings us to another reason to visit El Morro National Monument.

The “writings on the rocks” the name refers to are the more than 2,000 inscriptions that have been carved in the sandstone sides of El Morro at its base over the past 1,000 years of time, or more. The earliest are petroglyphs, images etched by Indians, perhaps those who lived on top.

Beginning in the early 17th century, the messages were left by Spanish and Mexican explorers and military men. And after the United States won the area in the Mexican-American War in the 1840s, the inscriptions were the work of American travelers and cavalry officers.

The earliest message not done by an Indian was left by the Mexico-born Juan de Onate, leader of a band of men who had just come from exploring far to the west and were on their way to look for the legendary seven cities of gold rumored to exist in what is today New Mexico and Kansas.

When his troops stopped at El Morro, Onate had carved in ornate lettering, “There passed this way . . .Don Juan de Onate, from discovering the South sea, on the 16th of April, 1605.” No gold was ever found, nor any cities other than the pueblo villages. Today the legends persist: the New Mexico county where El Morro is located is named Cibola, which was the name of one of the seven cities of gold.

Other inscriptions in Spanish followed Onate’s, many of them equally ornate and some of them longer. The messages left by American travelers tended to be much less wordy, and certainly less ornate, often nothing more than a name and date, such as “J. Pollock, June 1, 1866.” On occasion, however, they offered a bit more information: “J. Cunningham Montgomery County NY Aug. 10 1863.”

The 2000 inscriptions are a vivid history of El Morro Valley. A paved path along El Morro’s steep side makes viewing easy (except when the inscriptions happen to be high up} and there are translations and transcriptions to make for easy reading, especially when the messages have been worn away by time.

Inscription Trail goes by a large pool of water that’s partially under the massive cuesta, but which is always full. The Indians who lived there and the travelers who passed by could depend on that pool at all times to quench their thirst and that of their horses. It’s existence made certain that any one who found himself in El Morro Valley would eventually make their way to El Morro itself.

Candy Kitchen and the Wild Spirit Wolf Sanctuary

Candy Kitchen, New Mexico, isn’t much of a town. It’s more like a community – of ranchers, Navaho, and homesteading nonconformists – spread over a great deal of territory. It got its wonderful name, or so the story goes, during Prohibition, when a local entrepreneur and maker of booze regularly ordered large amounts of sugar to make his illegal product. So as means to conceal his bootlegging activities, he made batches of pinon nut candy which he sold over the counter – hence the town’s name.

To get to Candy Kitchen turn south off New Mexico 52 a few miles west of El Morro onto Route 125, a road maintained by the Bureau of Indian Affairs or BIA. Follow the signs to Candy Kitchen. You’ll pass through the village where the Ramah Navajo maintain their tribal headquarters. The Ramah Navajo are a branch of the much larger Navajo Nation (whose reservation is in the northwest corner of New Mexico and in adjoining parts of Utah, Colorado, and Arizona).

The Ramah Navajo supported the Pueblo Indians in their great revolt in 1680 when the rest of the Navajo Nation did not. The united Indian tribes slaughtered Franciscan friars and priests who were there to Christianize the Indians, and succeeded in driving the entire Hispanic population – those who survived the wrath of the Native Americans – out of Northern New Mexico south into Old Mexico. It took the Mexicans over a decade before they completed their reconquest of the region.

It was ranchers and ranch hands – and the Ramah Navajo – who populated the region in the 19th and first half of the 20th century. A remote area, it was famous for those who fled there. The Bedonkohe Apache leader Geronimo, one of the most famous of all Indian warriors, is said to have hidden from federal troops near what is today Candy Kitchen.

An old time resident – now long dead – was a cowboy named Henry Miller, rumored by many to have been Billy the Kid, the most famous of all Anglo New Mexicans. According to the story, Billy didn’t die when Pat Garrett shot him at Fort Sumner on the other side of the state in 1881. Severely wounded, he got taken care of by Hispanics whose language he’d learned and for whom he had been a hero.

They nursed back to health and he fled Fort Sumner for the western part of New Mexico where he took his identity and worked on until old age took him in the 1920s.

The story is unlikely – after Billy’s demise there were innumerable Billy the Kid sightings, just as there have been numberless Elvis sightings ever since the singer’s 1977 death – but the fact that the rumor exists and persists, is another example of Billy’s amazing perduring fame and the continuing power of his legend.

What draws most travelers to Candy Kitchen these days is the Wild Spirit Wolf Sanctuary, which is the comfortable home for 65 wolves (several are part-wolf, part-dog), along with a small number of New Guinea singing dogs, and a handsome fox named Romeo. A number of the animals are “rescues” from owners who thought it would be cool to have a wolf at home, and then found their “pet” far too much to handle.

The sanctuary, which is the creation of “Wolf Daddy” Leyton Cougar, is staffed by volunteers, who very obviously love working with the animals, and who conduct tours at 11 am, 12:30, and 2 in the afternoon. We were there in the morning and, by chance, I got to see the feeding of these large canines, which was a sight to behold.

But our most extraordinary experience at the sanctuary – and an experience we won’t forget – came during our tour, a walk around the huge compound where you’re introduced to the animals (they’re behind high wire-mesh fences). At one point, we noticed in the distance two wolves in a tussle, which, given their size, looked scary and potentially harmful.

Elaine, the young woman from Chicago who was our guide, noticed our concern. “Don’t worry. It’s nothing serious,” she said. “They’re just testing to see who is boss. It’ll be okay.” And, sure enough, it was. One of the animals suddenly pinned the other down, and the pinned wolf humbly submitted.

No blood had been shed. What followed was unexpected (by Ray and me) and magical. The moment the pinning took place and the defeated dog acknowledged its defeat, howls rose up from all over the sanctuary, from each of the 65 wolves, and the howling lasted for several minutes. It was a chorus of recognition of who was top dog. Being there and hearing the prolonged howl made us feel good. It made us feel a part of nature, a feeling that’s incredibly exciting to experience, the rare times it happens.

We’d never seen New Guinea singing dogs before. They too were there because their owner couldn’t handle them. They are as cute as dogs can be. Their howl is curiously melodic – hence their name. They look liked they’d make great pets – but Elaine said they don’t take well to domestication.

The sanctuary has a souvenir shop with great wolf-themed T-shirts and coffee mugs and much else, including copies of the sanctuary’s publication, called (what else?) “The Howling Reporter.” For more information check out the website. And oh yes, one thing I learned that I hadn’t known – wolves do not bark, they howl. So if you have a large dog that you think might be wolf – if it barks, it isn’t.

El Malpais National Monument

The Badlands deserve that name. They are severe and unrelenting. Hardened lava can cut through blue jeans and is hard on leather boots. I know: three years ago I fell in a lava field in El Mapais, and though I wore new jeans and good boots, I quickly became a bloody mess.

But the Badlands are beautiful country. Ray lovess to paint there and he’s done some of his best paintings in El Malpai . He likes to point out to friends back home in Delaware that “New Mexico’s badlands are fifty square miles larger than the State of Delaware”, a fact he seems to take pride in: It underlines the attraction the area has for him.

None of the volcanoes in El Malpais are active today. The most recent lava flow in the region, however, came from the McCartys Cone some 2,000 to 3,000 years ago, only a nanosecond in geologic time. Other cones are many thousands of years older. Underneath the land surface, but sometimes exposed to view, there’s a network of lava tube caves that’s at least 17 miles long, and caves where there’s ice all-year long.

Well-marked hiking trails take you to most of volcanic features of the region: the cones, the caves, the tubes, and rare manifestations such as xenoliths, rocks thrown up by the volcanoes from the deepest reaches of the earth. Today, much of El Malpais is covered with plant life – pinon, several species of juniper, Douglas-firs, and a wide variety of shrubs and wild flowers.

El Malpais is a National Monument, and there’s a ranger station on Route 53 with a ranger willing to dispense advice on hiking and what’s permissible and not when you’re there (forest fire is always a problem in dry New Mexico, and you’ll be warned if the chance of fire is high).

The most accessible hiking trail in the Badlands is in what is known as the El Calderon Area, named for the extinct volcano, El Calderon. The area is easily reached by a short drive off New Mexico 53 to the parking lot, which has restroom facilities. There’s a helpful map of the trails on a bulletin board near where you’ll park.

El Calderon’s cone formed about 115,000 years ago, when it sent out cinders into the air and rivers of molten lava. The cinders are now piled everywhere. The once molten lava formed trenches and underground lava tube – the caves – and they will most likely be off limits for exploration when you’re there.

The area for the most part is now covered with trees and other foliage, but significant volcanic remains are still visible at spots along El Calderon Trail such as Junction Cave, Double Sinks, Lava Trench, and Bat Cave. You can climb to the rim of El Calderon itself and look down into its crater.

Two summers ago, Ray and Pearl and I went further into El Malpais than we’d ever gone before (or since). It was a gorgeous warm New Mexico day with a bright blue sky and we took our four-wheel drive Dodge Nitro down County Route 42, which leaves Route 53 just west of the Bandera Crater and Ice Caves. It’s a dirt road that to our somewhat alarmed concern totally disappeared at times leaving us driving across what seemed trackless land. We worried that the road might not reappear (it did, to our considerable relief).

But the trip was worth it, every minute of it, despite our short-lived anxiety, and it proved to be one of the most exhilarating experiences we’ve had in New Mexico, or anywhere. Along our way, we stopped at what is called the Big Tubes Area and hiked – the volcanic remains are particularly dramatic and rugged here, and to our considerable delight we discovered desert cacti blooming – a vivid, intense Day-Glo red.

As we drove further South we passed the Chain of Craters Wilderness on our right, crossed the Continental Divide, and entered the West Malpais Wilderness. There we encountered two of the largest bulls we’ve ever seen, part of a rancher’s magnificent herd, with massive horns. When first seen in the distance, looming on the horizon, they looked bigger than elephants, and more impressive.

But most magically of all, there were dozens of pronghorn antelope, a few drinking at pools of water, and others racing at full gallop in pairs and groups of four, looking like they were having great fun and very much pleased at being alive. Their vitality and grace were splendidly visible, and we looked on with admiration and delight.

County Route 42 eventually runs into New Mexico 117, which took us along the eastern edge of El Malpais (on our left as we drove north) and the dramatic sandstone ridge (on our right) that is the western end of the Acoma Reservation. On the way, we passed another of the region’s natural wonders, La Ventana Natural Arch. Then it was back to Ancient Way for dinner and a night’s rest.

For more on the road with Stephen Goode read ‘Billy the Kid‘ story.

Steve Goode grew up in Elkins, WV in the 1950s – a fine time and place to be young

– and attended Elkins public schools. He holds a BA from Davidson College, an MA from the University of Virginia, and Ph. D. from Rutgers – all in history – but pursued a career in journalism rather than academia. For 20 years he wrote on politics and culture for Insight Magazine and the Washington Times. He is the author of 17 nonfiction books and numerous articles in various publications. With his partner of 40 years, the botanist and artist Ray Petersen and their dog Pearl, he divides his time between their home in Milton, DE and a condo in Albuquerque, NM.

Dang, now I know I must spend more time in this part of the world. So much magic. Thanks for the great article!

Tim A., thanks for sharing this article and for all that you & Lucia do to bring that beautiful corner of the planet alive. Steve, if you have a chance, give me a tap back at [email protected] as there are some other aspects of the area I’d like to mention to you that would be worth your time next visit. jay in savannah (and occasionally Ramah)

Excellent article, enjoyed it very much! Makes me want to see the places in the area I have not been to yet!

(Does have some typos, sorry to mention).