Two cases linked in history galvanized the civil rights movement

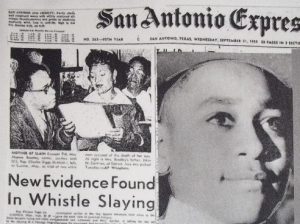

Original Caption: Sinking to knees, Mrs Mamie Bradley weeps as body of slain son, Emmett Louis Till, 14 arrives at Chicago Rail Station. The youth was found dead in a Mississippi creek with a bullet hole behind the ear. Being sought in connection with the slaying is Mrs. Roy Bryant, at whom the youth is supposed to have whistled a “wolf call.” Held also are store keeper Roy Bryant and his half brother, J.W. Milam. With the bereaved woman are left to right, Bishop Louis J. Ford; Gene Mabley; and Bishop Isiak Roberts, of St. Paul’s Church of Christ and God.(HANDOUT)

BALTIMORE — Sixty-three years after the horror, the federal government has decided to re-open its investigation into the murder of Emmett Till, the 14-year old African-American boy whose brutal killing in Mississippi became a symbol of racial violence in 20th century America.

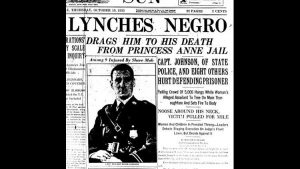

Eighty-five years after a similar horror, no one is re-opening the case of George Armwood, a 23-year old African-American man whose grotesque killing in Princess Anne, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, was a gruesome example of that era’s mob violence.

But the two cases are linked by history.

But the two cases are linked by history.

The killing of Till became a catalyst for the great American civil rights movement. The killing of Armwood, largely forgotten today, became the catalyst for one of the nation’s greatest civil rights careers.

The government says it’s re-opening the Till case because of “new information.” In the summer of 1955, Till was visiting family in Mississippi when he went to a store owned by Carolyn Bryant Donham and her then-husband.

She told a variety of stories about Emmett. In one, she said he whistled at her. In another, he insulted her. In a third story, she said young Emmett touched her hand. In the mid-century American South, this was enough for two white men to kidnap Till, tether his body to a cotton gin fan with barbed wire, and then dump him in a river.

In 2008, Donham said it was “not true” that Emmett had grabbed her or made vulgar remarks. In a book published last year, she added that “nothing that boy did could ever justify what happened to him.”

In 2008, Donham said it was “not true” that Emmett had grabbed her or made vulgar remarks. In a book published last year, she added that “nothing that boy did could ever justify what happened to him.”

In 1955, an all-white jury acquitted the two men arrested for the murder, one of whom was Donham’s husband at the time. Since then, both men have died.

But it was the publication of photos of Emmett’s open coffin, and his mutilated body, that stunned the country and energized a civil rights movement that was beginning to find its strength with Rosa Parks’ bus ride, and sit-ins and voting rights marches across the south.

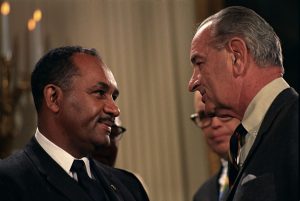

Poor George Armwood died years too soon for that movement – but his death so inspired a young Clarence Mitchell Jr. that he became one of the great leaders of that civil rights era.

Mitchell, who grew up in West Baltimore, graduated from Lincoln University and returned to his home town to work as a reporter for the Afro-American newspaper. When word reached the paper of the killing of Armwood, Mitchell was assigned the story.

Armwood, who lived with his mother, allegedly assaulted a 71-year old woman but ran off when she screamed. The woman was white. When Armwood was arrested, a mob gathered outside the Princess Anne jail and pulled the terrified man from his cell, cut off his ears and pulled gold teeth from his mouth. His body was hanged from an oak tree on an old woman’s lawn near the jail.

“This,” said Mitchell’s son, former State Senator Michael Mitchell, “was my father’s real awakening about man’s inhumanity to man…This moment made him rededicate his life – to calling on the fundamental decency in people.”

Mitchell and a photographer were quickly dispatched to the Eastern Shore, where they found Armwood’s brutalized corpse still on display, intended as a signal to other blacks: here’s what can happen to you if you step out of line.

And here’s a piece of what Clarence Mitchell wrote in his front-page story in the Afro-American newspaper:

“Silent groups of our people on their way to work…solemnly gazed at the horribly mangled corpse which had been stripped of all clothing and was covered with two sacks. The skin of Armwood was scorched and blackened while his face had suffered many blows from sharp and heavy instruments.

“A cursory glance revealed that one ear was missing and his tongue between clenched teeth gave evidence of his great agony before death.”

The experience led Mitchell toward one of the great roles in the American civil rights movement.

He helped lead the national office of the NAACP. He helped desegregate every major federal agency in Washington. He convinced Congress to pass the first civil rights act in 83 years, from which came laws banning housing discrimination and ensuring the right to vote.

He testified so many times – more than a hundred – before various Capitol Hill committees that, near the end of his career, he became affectionately known as the 101stsenator.

As the government re-opens the case of Emmett Till, it’s comforting to note that his killing helped spark the great mid-century civil rights movement.

Few people today remember the case of George Armwood. But it’s comforting to note that it helped inspire Clarence Mitchell Jr., who in turn inspired so many others.

Michael Olesker, columnist for the News American, Baltimore Sun, and Baltimore Examiner has spent a quarter of a century writing about the city he loves.He is the author of several books, including Michael Olesker’s Baltimore: If You Live Here, You’re Home, Journeys to the Heart of Baltimore, and The Colts’ Baltimore: A City and Its Love Affair in the 1950s, all published by Johns Hopkins Press.