‘Reflections’ links past to present at Maryland Historical Society

Masked police officials attend a demonstration in a gripping image from Reflections: A Brief History of Looking at Ourselves. (courtesy Maryland Historical Society)

Baltimore — In a world where we are constantly bombarded with instant images, it is easy to forget that there was a time when posing for a photograph was a complex affair. But even in the stoic portraits of the past, one can still see the common threads of life which link the daguerreotype to the modern cell-phone camera.

Exploring these fascinating threads is a new exhibit at the Maryland Historical Society, fittingly titled Reflections: A Brief History of Looking at Ourselves.

Reflections opened this past Wednesday evening and runs until July 1, 2020.

Co-curated by Joe Tropea and Elena Volkova, the exhibit, “explores themes of identity and place that are the cornerstone of human experience.”

“We knew it was the 180th year of the birth of photography, and we wanted to do something to celebrate the occasion,” explained Tropea – Curator of Films and Photographs at the Maryland Historical Society. “We have a vast collection of photos – so many, in fact, that you’d need a much larger space than this room to do an exhibition justice. So we centered this exhibit on portraiture. As we looked at all of our images, the portraits really stood out.

“Early on, we noticed that some of the portraits remind us of things we see today on Instagram, so it is interesting to see, even with how much photography has changed, how much about us is still the same.”

Tropea pointed to one example of what many today would see as a commonplace occurrence – a series taken by a photographer named John Dubas (1889 – 1976).

“From the 1930-1950s, Dubas took sixteen self-portraits, or better, “selfies” of himself sitting at a desk – many with a calendar visible. So we know what month and year it was. Looking at those images just felt so familiar – to think that people were doing that as far back as the 30s, 40s, and 50s. And that became part of our theme.

“But we wanted to tackle other themes, too, like identity and place. Just how we present ourselves in photographs. From more than a million photographs in our collection, we paired down to about 130, then paired a few more so that the exhibit would fit into this gallery room.”

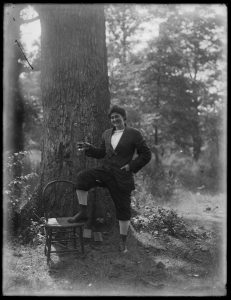

For some of the subjects, the location could be a front porch, a factory entrance or construction project. Identities range from the “Chocolate Dandies” chorus line and members of James Reese’s Harlem Hellfighters Band, to a smiling secretary anxious to show off her depression-era Argus camera.

Then there are those hauntingly beautiful stoic images our ancestors held so dear.

“We have a case which features the only original images in the show,” said Tropea. “For the sake of preservation, everything else on display is a reproduction.”

A case full of daguerreotypes?

“The cased photos are not just daguerreotypes, but also opalotypes, ambrotypes, carte de visites, and cabinet cards. There is even a tintype thrown in. We wanted to capture some of the earliest formats and display them together.

“One interesting thing is: We found a few instances where we had multiple images of individuals. It was fascinating to find four shots and watch one fellow age from a young child to a middle-aged man. With another man, we get to see how he visibly aged during the Civil War. They say you can see the same thing with how the Civil War aged Lincoln.”

Tropea said the oldest image on display is on loan to the society from the collection of Ross J. Kelbaugh.

“You can hardly see what’s in the image – it’s almost like a ghost – but we believe it’s among the first daguerreotypes taken in Maryland. The very first studio here was set up by Henry Fitz, Jr. (1808 – 1863) and this ghostly image dates from around 1840. Ross lent us two others as well, including an image from 1860 of a young, unidentified washwoman with a washboard in the photo. It’s an interesting representation for that time – to see a laborer like that. It’s certainly something that you don’t see a lot.

“There are 68 reproductions, 28 original items in the glass case, and I’m told our Instagram feed holds up to 80 additional images. Add those up, and that’s the total we are presenting for this show.”

We asked Tropea why so many of the images on display (about 40 of the 68 reproductions) are untitled?

“That’s the reality of our collection. In some case, the provenance is quite murky. Rather than take guesses, we just decided to go with ‘unknown’ if we really weren’t sure. Many of the subjects are unknown, as are many of the people who took the pictures. We may know a name but not a date, or know who the subject was but not the photographer. And we don’t always know the year in which the picture was taken.

“We worked with some experts on dating the images on display. It’s a lot easier when the images have women in them, because of the clothing they are wearing. Men’s wear is less telling. And even when men’s fashion changes, men tend to hang onto the styles they like wearing much longer.”

With so many images on display, we wondered if the two curators could point to a favorite?

“I have a few favorite pieces,” said co-curator Elena Volkova. “But ‘Theresa and Jim as Lovers’ is both mine and Joe’s favorite. That is why it is posted so big! I love it because it is a very private scene.

“It is very unlikely to put on display one’s private life. But as you keep looking at it, all of these questions come up.

“Obviously, they are sitting on an unmade bed. What is not obvious is that Jim (James Lewis, 1881 – 1959) is the photographer. There is not another photographer in that space. So, he’s taking a picture as he is posing for one. He has made a decision to look away from the camera and be observed by the viewers, while his wife is looking into the lens and making eye-contact with us. She has this Mona Lisa smile, so there’s a subtle seduction, but it’s a wonderful image.

“As we worked, I thought, ‘What if we keep digging? What else might we find that would otherwise never see the light of day?’ So, maybe we’ll keep digging and produce another show!”

It is estimated that some 95 million photos and videos are posted every day on Instagram. I’m guessing more than a few are by smiling secretaries anxious to show off their new cell-phone cameras.

* * * * *

Reflections: A Brief History of Looking at Ourselves runs now – July 1, 2020 at the Maryland Historical Society. The MDHS is located at 201 W. Monument Street in Baltimore, Maryland. Ample parking is available on the premises. For more information about Reflections, including admission times and tickets, as well as other current and upcoming exhibits, please visit the MDHS.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”