Old fashion ride on the Santa Cruz Local gets me going again

In “The Circus Animals’ Desertion,” Yeats wrote about the loss of youthful elan: “Now that my ladder’s gone, I must lie down where all the ladders start, in the foul rag-and-bone shop of the heart.”

Personally, I’d call a carpenter, but a train ride can lift me out of the shop too. Three days a week, the Santa Cruz Local starts in Watsonville and heads 31 miles up Santa Cruz County to the LoneStar cement plant in Davenport. In order to catch it, I appeared in Watsonville on a Sunday evening and trudged a mile up a country road to my permitted luxury, a motel. As I rounded a bend, a mariachi band began playing, a good surreal prelude to an unpredictable hobby.

The next morning, I sat under a trestle on the banks of the Pajaro River. I hopped the first thing in sight, a four-car train, nearly breaking my arm on a tardily spotted signpost. It had barely left downtown Watsonville when it halted and a crewman called out, “Get off! End of line!”

Just a switcher. “Nothing to Davenport today?” I asked his partner.

“Comin’ along about a half hour later,” he shot back.

Why can’t academics be so concise? I was standing in a field of iceberg lettuce and decided that, being taller than most rodents, I needed better cover. Eventually I hid among piles of farm equipment until the real McCoy, a four-unit, nine-grainer consist, chugged into sight.

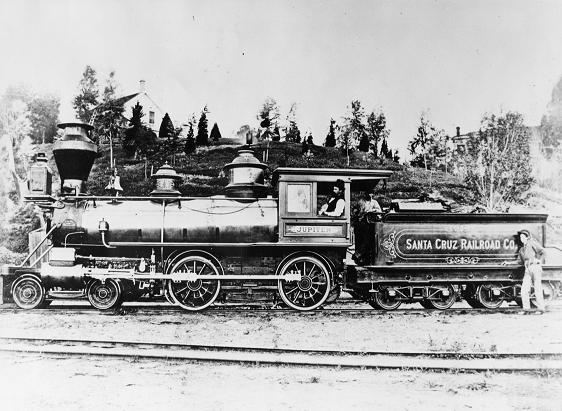

This trip had a fine old-fashioned feel to it. In the modern age, most freights are mile-long hotshots that cross the continent. Riding a short local, all I needed in addition was to see a steam engine at the head. That aside, the scenery possessed great diversity. A Pajaro Valley strawberry field announced itself with its rich fragrance, tempting me with thoughts of aborting the trip. After that, between Watsonville and Aptos, the line crossed wilderness verging on the ugly – rank, overgrown wetlands.

Past that national wildlife refuge, the county alternated between wealthy little towns and dark, deep, shaggily wooded canyons. As we cruised past a beach and into Aptos, the human dimension emerged: surfers waiting to cross the tracks, a lone painter composing a seascape, rich people standing on their balconies. We crossed a trestle overlooking a huge, colorful marina and, bang, we were in Santa Cruz. Awkwardly for publicity-shy train-hoppers, the tracks run along the Boardwalk, under the rollercoaster (!), then down the middle of a crowded street. Hundreds of tourists lined the tracks; the air rang with the cries of children riding the Coaster and the Ferris wheel.

To my amazement, three different people (two boys, one man) had jumped the train for short trips. The boys rapidly bailed out, but the man hung on until Santa Cruz. An impulsive pedestrian, he had just saved a dollar’s bus fare. On the one hand, I was appalled to see inexperienced locals risking their lives; on the other hand, I had been one of them and had to admire the local spirit of participation.

We broke free of the jam-packed streets and, along the North Coast, the train sped up. A blustery, cold wind whipped up dust and pesticides from the seaside farms, forcing me to turn away and shut my eyes for much of the time. The views, though, were stupendous. We were running much closer to the ocean than did Highway 1. From my grainer deck, I peered over raw, twisted cliffs into a string of jewel-like inlets. At the foot of those cliffs, breakers rose above cobalt-blue waters and crashed against unspoiled pocket beaches. With every glance, I hungrily gulped in the tangy ocean air. As soon as the train stopped at the LoneStar plant, I ran past UNSTABLE CLIFFS signs, past the elevation marker (80 feet), and scrambled down an eroded, talus-strewn trail to one of those beaches. I kicked off my shoes and stood exultantly in the freezing Pacific.

Why do we hop trains? The reasons are endless, but I would say that riding them has always given me hope. They constitute a precious escape from realities I would rather not face.

In real life, we grow old, we lose in love, we abandon our dreams. Nobody can defeat the laws of gravity and mortality. Aboard a freight, headed for the horizon’s vanishing point, we can.

Abdul Rahimov has a Ph.D. in Russian history from Stanford. He studied earlier at Harvard and grew up in Illinois in a railroad-dominated town.Rahimov prefers to use a pen name to avoid attracting unnecessary attention from railroads. He lives on the East Coast.