Jim Bouton’s ‘Ball Four’ changed the game for sports writers

BALTIMORE — In all of the culture wars waged across America over the last half-century, Jim Bouton hurled some of the most compelling strikes. He didn’t just write a baseball book, which was called “Ball Four.” He taught us a new way to look at our heroes.

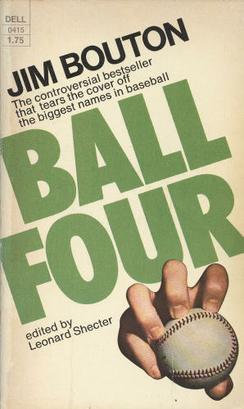

When he died last week, at 80, all the obituaries cited his literary legacy more than his lifetime pitching record. No wonder. Sports Illustrated called “Ball Four” No. 3 on the top 100 sports books of all time. The New York Public Library made it the only sports book on its 159 greatest books of the 20th century.

But the big shots in baseball hated it. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn called it “a great disservice to the game.” Many players, including Mickey Mantle, considered Bouton a pariah. The tough New York Daily News sports columnist Dick Young called Bouton “a social leper.”

But readers loved Bouton’s book, and made it a giant best-seller. It was an early signal in a generational shift in American thinking, a casting off of many of the old cultural constants and a re-examining of who we were, as if part of a national jigsaw puzzle whose pieces no longer seemed to fit.

In the 1960s, a time of political assassinations, racial upheaval, anti-war demonstrations and college campus uprisings, Bouton brought America some unanticipated truths about professional athletes: they weren’t sun gods descended from Mt. Olympus, they were boys with a bit of the devil in them. They did remarkable things on ballfields but were given to childish, profane, funny business when they thought nobody was watching (or taking notes.)

In the 1960s, a time of political assassinations, racial upheaval, anti-war demonstrations and college campus uprisings, Bouton brought America some unanticipated truths about professional athletes: they weren’t sun gods descended from Mt. Olympus, they were boys with a bit of the devil in them. They did remarkable things on ballfields but were given to childish, profane, funny business when they thought nobody was watching (or taking notes.)

“Ball Four” was a deeply funny book, but it was also part of an era when Americans were taking stock of our old myths and replacing them with gimlet-eyed reporting, which was sometimes painful but at least based in reality. If we could admit to athletes’ human errors, maybe we could also start questioning, for example, the previously-disguised human errors of politicians, or the egotism that got us into such a mess in Vietnam.

After Bouton’s book, to accept the old, unquestioning ways of seeing the world was to be considered a bit of a chump.

“Ball Four” helped launch a whole new era of sports writing, as well. Gone were the days of hero worshippers such as Grantland Rice, who immortalized a college football backfield “outlined against a blue-grey October sky…the four horsemen of Notre Dame.”

It was years later when the great sports columnist Red Smith finally noted, if Rice could see them “outlined against a blue-grey October sky, I wonder what angle he was watching the game from.”

By Smith’s later years, the best sports writing – unleashed after Bouton liberated it, and showed how popular it could be – you had Roger Kahn, in 1970, with Richard Nixon in the White House and war raging in Vietnam, making this connection between pro football and the larger world:

“Well, professional football is only a game. Its heroes drive forearms into throats at 4:15 p.m., and then they kneel in group prayer at 4:20. No one who knows that should have been surprised when an administration ruled by a football idolator ordered Cambodia invaded on a Thursday and proclaimed for that Sunday, ‘Let us pray.’”

You take sports writing into such emotional precincts, and before you know it, you’re reporting about jocks and labor issues, and drug and alcohol abuse, and steroids, and football brain injuries.

Bouton’s book was mainly light and funny. But, in the course of describing big leaguers who played Peeping Tom through hotel windows, or considered themselves “married, but I’m not a fanatic about it” during road trips, he was upsetting all those heroes accustomed to being lionized who imagined it would always stay that way.

“Ball Four” told writers it was all right to look beyond the playing field. And not only sports writers. The book opened the door for movies such as “Bull Durham” and “Major League” and “Moneyball.”

We wanted to know truths about our public giants that ultimately reduced them to our size – human size. “Ball Four” helped set all of that into motion.

Michael Olesker, columnist for the News American, Baltimore Sun, and Baltimore Examiner has spent a quarter of a century writing about the city he loves.He is the author of several books, including Michael Olesker’s Baltimore: If You Live Here, You’re Home, Journeys to the Heart of Baltimore, and The Colts’ Baltimore: A City and Its Love Affair in the 1950s, all published by Johns Hopkins Press.