Exploring St. Louis’ sights not on the tourist map

St. Louis always has occupied a peculiar lacuna in my personal history.

It was the big city nearest to my hometown but was in long-term decline and lacked several attributes that Chicago had. Well over 90 percent of the time, if my parents wanted to do something in a big city, they steered the car north rather than southwest, up toward the Second City.

St. Louis, only two hours away, had almost no resonance for me: the only images that I could conjure up were the Gateway Arch, some Cardinals games, my brother’s residence for a few years. Later, I decided to rectify this oversight of my childhood and was able to stitch together a friend’s private plane, Southwest, Greyhound, and Amtrak over a long weekend.

St. Louis has one of the most mysterious histories of decline of America’s cities. Without having had riots like Detroit, Newark, or Washington, it emptied out at a pace that even its traumatized rivals could not match. In losing 61 percent of its population from 1950 to 2000, it allegedly experienced the greatest population loss of any city since Carthage, though surely some Nazi- or Soviet-occupied cities could have competed for this honor.

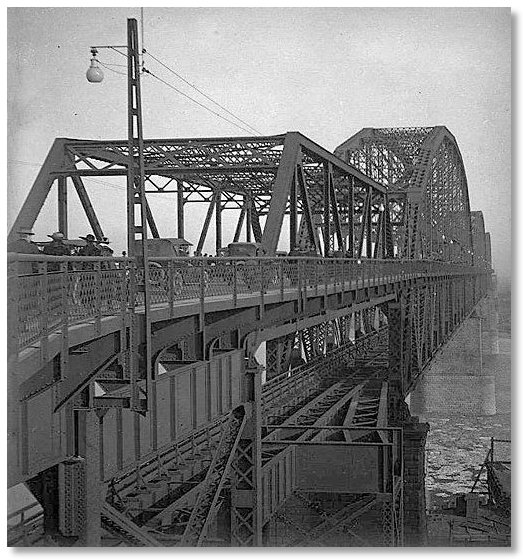

It has five car bridges across the Mississippi, but at times as few as two of them have been open, owing to amazing fecklessness by local authorities whenever a bridge has deteriorated. The steel-truss “Free Bridge” built in 1917 and renamed the General Douglas MacArthur Bridge in 1942, has been a railroad-only span since 1981, when part of the upper deck gave way.

The current owner, a railroad consortium, has chopped off a segment of road at the eastern (Illinois) end to make the car ban permanent. From the riverbank, you can see the parallel 19th-century spans, all of which have the titanic and elegant Industrial Age ironwork that nobody builds anymore.

As soon as my Southwest flight landed, I picked up a transit day pass. Although America has nothing but contempt for those without cars, Rust Belt inner cities generally have tolerable transit serving their short distances. I rode light rail to Busch Stadium and headed south through deserted streets lined with old brick buildings until I reached Gratiot St., where a Ralston-Purina plant faced the blocked-off beginnings of the MacArthur Bridge.

At the very start of the approach several MDOT trucks blocked access to a chain-link gate topped with a single strand of barbed wire. I went over it and kept going until I hit a second gate. You do not appreciate the dimensions of something engineered for cars unless you trudge, trudge, trudge uphill for several hundred yards and find yourself facing a second gate topped by three strands of barbed wire, still short of the river and a couple stories above street level. I-55, screaming with cars and the potential eyewitnesses inside, ran below. The pounding sun evoked the city’s longtime reputation as major-league baseball’s worst hellhole in the summer.

The humorless highway bastards had laced the ends of the gate with coils of razor wire to deter trespassers. Nevertheless, I figured that the chance of falling to my death going around the gate was somewhat smaller than the chance of being badly cut going over the gate, so I swung out above the city, treading on the razor wire and ferociously gripping the gatepost.

The pavement looked surprisingly good for not having been maintained in 24 years. I headed toward Illinois more than 14 stories above the unappealing Big Muddy, while frequent freight trains accompanied me underneath. It was odd, and immensely silent, to have the entire deck of a cross-river bridge to myself.

The tourist trap Laclede’s Landing and Gateway Arch stood to the left; on the right a line of trees blocked views of hideous and dysfunctional East St. Louis on the Illinois shore. At the east end the road jaggedly ended in mid-air as I knew it would – an asphalt cliff – about 20 feet above the railroad tracks.

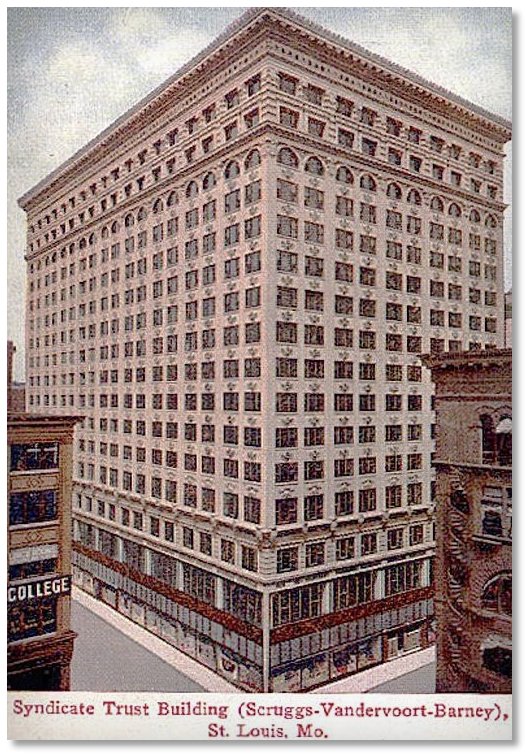

It was time now to drop back down to earth on the St. Louis side and catch light rail over to 8th and Pine, the station nearest the Syndicate Trust Building (see photo at bottom of page), an 18-story terra cotta office building downtown, built in 1907 but abandoned in the 1980s.

Thanks to a renovation boom sparked by a well-thought-out tax credit, Syndicate Trust has actually been saved and will emerge as condos in 2007. But work has not started yet, so I thought that on this Saturday afternoon I could sneak in and look around. I clutched only two certainties: 1) the Syndicate Trust stood on 915 Olive. 2) I was going inside somehow. Shy but relentless is not the personality I would have chosen, but you don’t get to choose these things.

I went thru a gap in the contractor’s chain-link fence, glared misanthropically at the few weekend passersby until they vanished or looked at more interesting objects, then popped through an unlocked, plywood-clad door into musty darkness. The darkness was total, pierced only by my flashlight, until I reached the 6th floor or so, when I found a stairwell with un-boarded-up windows. The depressing thing about most abandoned buildings is that they lack a romantic frozen-in-amber feel, the impression that somebody walked away from the desk just yesterday.

In Rust Belt cities with bad weather, if the windows are left open, the interior falls apart fast. You find piles of fallen plaster, sagging ceilings, stairs missing treads or risers, skeletonized animal remains, elevator shafts gaping dangerously open so that you can see the roofs of the cabins at the bottom.

I plowed upward past offices where long-dead businessmen had admired the views of a bustling city that had hosted both the Olympics and the World’s Fair in 1904. One of the higher floors still had what was once clearly a company head’s paneled office; I found a mountain of cancelled checks from the 1980s nearby.

Ultimately I reached the attic equivalent and shoved through the roof access door. Eighteen stories up, drinking in the view, I noted the Old Post Office next door and the anachronistic red brick steeples that spoke of German immigrants whose descendants had since vanished into the suburbs.

On the way down, I momentarily panicked about the sole way out. Amid the darkness of boarded-up lower floors where piles of debris all look the same by flashlight, it can be quite easy to misplace the exit. In Detroit I had had to jump off a fire escape after forgetting how I had entered the former Statler Hotel. During my search I repeatedly passed a clock repair shop’s facade, frozen in time in a ghost arcade.

I kept moving, trying out different ideas, even stepping on a nail but not drawing blood, until the unavoidable truth stared me in the face – the fifth was the only floor where I could connect to the one staircase descending to the exit. I had been lazily trying to find a connection on other floors. Not caring who saw me now, I burst out onto the street in pursuit of Greyhound.

A hometown was waiting two hours away.

Abdul Rahimov has a Ph.D. in Russian history from Stanford. He studied earlier at Harvard and grew up in Illinois in a railroad-dominated town.Rahimov prefers to use a pen name to avoid attracting unnecessary attention from railroads. He lives on the East Coast.