ER Dr. Shannon Sovndal Sees Hopeful Signs Amid COVID-19 Crisis

Boulder, Colorado — Through numerous conflicts and natural disasters, Americans have become aware of the physical and psychological toll exacted upon our front line personnel. But not since the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1920, has our society witnessed a health event of such catastrophic proportions that has touched each and everyone’s life. Particularly at risk are the men and women who work as first responders and on medical teams. To understand what they are experiencing as they care for the seriously ill, we spoke with Dr. Shannon Sovndal

Dr. Sovndal serves as a physician and medical director for multiple EMS agencies and fire departments in Boulder, Colorado. He has a wide range of career experience, working in tactical medicine (TEMS) with the FBI, as a team doctor for the Garmin Professional Cycling team, and as a flight physician.

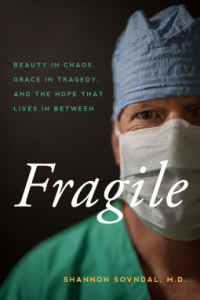

Sovndal is also the author of a new book titled: FRAGILE: Beauty in Chaos, Grace in Tragedy, and the Hope that Lives in Between (2020 Gryfalcon Press). In his emotionally-charged memoir, Sovndal examines the tenuous balance between compartmentalizing the trauma of tragedy while preserving his humanity.

BPE: Please allow me to start by asking the obvious question: How are you holding up?

Dr. Sovndal: I’m good. We kind of knew from the beginning that we were in for a long run, not a short sprint, so we’re trying to pace ourselves.

BPE: What are you seeing with patients who come into the ER?

Sovndal: The first thing that’s notable with all of this is that the volume of patients with other complaints has dropped. I think that people really are taking heed of that warning to stay home and only use healthcare facilities, if you really need it. In the ER, we still see car accidents, and heart attack patients aren’t diverting, but we’re not really seeing the lesser complaints.

And then there’s this Covid-19 population.

For me, it’s interesting because, even at one time, I had four patients that I was sure were Covid-positive, and they kind of ranged the spectrum of the disease. Meaning, my first patient was an elderly man in his eighties, with very low oxygen saturation and quite ill. The next was a younger female who looked like she had the flu. She was uncomfortable but was doing okay. The third was probably early on in the illness and was pretty well off. And then there was a middle-aged person that was medium; I was worried about which direction he would go.

It’s interesting, because you’re seeing this spectrum of the disease all at the same time.

BPE: So the idea early on that it would be people in their sixties and above – or those with pre-existing conditions – is not really playing out the way that they had predicted?

Dr. Sovndal: Yes, the interesting part is that we initially said it was the elderly who were going to get sick from this, but for everyone else, it would be a mild illness. But we’re not in that. There are different rates of complications for all the age groups, although the elderly age group does have a higher range of complications. But that doesn’t mean that the middle-aged group, or even the young age group, is immune to having complications. They are having it at a significant rate, meaning they are at 1% rate, 2% rate, and that’s obviously concerning. In Colorado, the average age of people with Covid currently is 49, and I’m a 49-year-old physician, so it definitely hits home for me.

BPE: Given that Colorado was one of the first states to legalize marijuana use, are you seeing any correlation between marijuana, or smoking or vaping, and the people who are coming in with Covid-related breathing problems?

Dr. Sovndal: I don’t think I could speak scientifically about that. We have a large population – obviously – of marijuana users and vapers. And I will say that smoking increases your risk of complications from Covid.

That’s really any kind of smoking, because when you inhale any type of marijuana or cigarettes, it injures your cilia and your protective mucus and all the things that prevent you from getting a virus. I think, as we move forward, it would be interesting to look at the data with vaping; there’s just a lot we don’t know about vaping overall.

BPE: How many people have your area hospitals treated for COVID-19?

Dr. Sovndal: In our county, we have 300 confirmed cases. Of those, there are 30 or 40 outstanding cases with people in the hospital.

BPE: How many medical facilities are there in Boulder?

Dr. Sovndal: We have 3 or 4 primary hospitals. Now, those are admitted patients. The tricky part about this is that I probably saw 12 people that I would think had COVID-19. But we don’t have enough tests, so the only people that got tested, were those that were admitted. I probably discharged ten without tests.

It skews the number quite a bit, as to what are the confirmed cases. We think, from a medical standpoint, it’s quite prevalent in the community. That’s why we wear protection with every patient we see. It’s more a matter that we don’t have the tests to test anybody who comes in worried that they might have a problem.

BPE: This gets into the number game – confirmed cases versus assumed cases?

Dr. Sovndal: Yes, absolutely. I think our true number for positive cases is much larger than what we see on the graphic.

BPE: What can families of those afflicted expect – both short and long term?

Dr. Sovndal: The question is whether they are distant family or local family. My son’s best friend’s grandmother just passed away from Covid. She was an elderly woman, but it’s interesting, because they can’t go see her. They can’t even go to the funeral.

The thing people are finding out is, when someone catches Covid, and they become significantly ill from it, the hospital is not even allowing family members in the room. They’re really minimizing who can be there. That is one major concern that a lot of physicians have, because if you get this and you become severely ill or you are passing away, you are doing it alone. You are doing it without your family present, because everyone is in isolation.

If you are in a family unit in a house, and someone comes home, and they have Covid, then we know that the transfer rate is probably 2 to 3; meaning that, for every one person that gets it, they transfer it to 2 to 3 people. So, if you’re living in close proximity, there’s certainly a high potential that other family members are going to get this disease as well.

Science still holds that, for the most part, this is a viral illness, like other viral illnesses that you see, and the recommendation is for you to stay home, unless you are having a complication that needs to be taken care of.

If a family member tests positive, it is our recommendation that they isolate. If I were to feel ill, I would move away from my family and be staying somewhere different.

BPE: Is that kind of self-isolation doable for physicians?

Dr. Sovndal: I just got an update from ACEP – the American College of Emergency Physicians – that some hotel chains are offering emergency physicians free hotel rooms, so that they can isolate themselves away from their families.

BPE: I think our readers got a sense of how isolation is playing out for the elderly and infirm in a recent interview we did with a hospice provider. We were told that families are being forced to say their goodbyes via Skype or over the phone, while the hospice nurses are there during the final transition.

Dr. Sovndal: That’s true, and I believe this whole social distancing directive is going to be a problem for us. We know that there are high levels of PTSD and stress among healthcare providers and first responders; high rates of depression and suicide.

First responders are really good in the moment. They are able to step up and put their feelings aside and kind of work through it. But with a prolonged issue like this, where you are dealing nonstop with the stress of seeing a lot of very sick patients, you add the secondary stress of concern for your own well-being and potentially infecting your family. Then add to that the potential that you won’t have any support network, when you come off your shift. That all combines to make for some very difficult concerns, moving into the future.

I think it’s really important to underscore here that we’re emphasizing physical distancing, which is different from social distancing, which is the term we’ve been using for it. You really need to figure out ways you can stay in contact with your support group, whether that’s Zoom dinner meetings or birthday parties or regular-scheduled coffee outings, where you’re doing it over Skype or a chat on the phone. Things like that, where you’re really staying connected to people, so that you can decompress a little bit.

BPE: You mentioned not having enough test kits. Do you believe the government is doing all it can at this point?

Dr. Sovndal: As a person on the ground, I think it is stunning that we don’t have enough personal protective equipment – that we can’t ramp up production in a war-time fashion. It’s truly a battle that we’re in right now.

BPE: You’re working with sick people while simultaneously playing a waiting game?

Dr. Sovndal: I guess in my mind, the solution to this problem is having more tests. We’ve seen in other countries how mass, rapid testing can really curtail the spread of the disease. Even more so with social distancing, because if you can start isolating the people who have the disease and their core group, you can free up others to do tasks necessary to keep our country moving.

BPE: What do you think can or should be done right now?

Dr. Sovndal: Certainly streamlining testing processes would help a lot. That’s probably the hardest part, because you want to make sure that the tests are valid and don’t give you false positives or negatives. We’re straddling this fine line of rapidly approving the tests, while making sure they work as well. We’re also hearing a lot of rumors about new types of tests coming down the pipeline, but I haven’t seen that pan out as of yet.

The process is similar to the other viral tests that we already do, so it’s not as if we are starting from scratch. We just need to isolate COVID-19 and find what triggers that test.

The other major issue I’ve found is that there are a lot of makers out there who are advertising their tests, which is causing first-responder agencies to rush out and purchase them. But the advertising is somewhat misleading, because those tests are looking for any kind of coronaviris – not specifically COVID-19. All kinds of coronaviruses are prevalent in the general population, so now, if firefighters take this test and wrongly believe they are positive for COVID-19, you needlessly diminish your response force at a time where all hands are required.

That’s part of the regulatory process, which gets back to your question about the government response. We really need to get the right tests out there.

BPE: Might those false-positive tests be picking up antibodies from an illness you’ve already gotten over?

Dr. Sovndal: It depends on the type of test, since you can test for different things. Our immune response is time-dependent, so different immunoglobulins which help me fight that virus may be floating in my blood. Knowing if I am infected versus I have been infected gives me a time frame, which can be very helpful. Oftentimes, long-lasting antibodies – things that are floating in my blood to protect me the next time I see a virus – can cross-pollinate a test and give me a false positive for COVID-19.

BPE: How are your supplies holding out?

Dr. Sovndal: That depends on where you are asking me. As the Medical Director for our city and county fire department, I can tell you that some fire units were better prepared with their stash of supplies. The hospital where I work currently has enough protective equipment, so I’m protected when I’m at work, with the caveat that I am reusing my protective equipment.

The ‘normal’ three months ago would be, every time I go into a room and I feel like I am exposed, I would doff that equipment and throw it away. Now, we’re saving that equipment; we’re putting it back on.

BPE: Doesn’t that impose a real risk?

Dr. Sovndal: The biggest risk to me is putting on and taking off my protective equipment. That’s where I have to be the most careful, and that’s where infection is most likely occurring.

When I have my protective equipment on appropriately, and I am in the room with a patient, I am protected, even if I cross-contaminate.

We had a protective drill, when we had the Ebola scare a few years ago. We sprayed ourselves with a substance that lit up under blue light and then doffed our gear and looked at ourselves under the blue light. You would be amazed at how much of this substance you had on you, once you took your protective equipment off.

That’s the problem we’re running into by re-using equipment. It’s dirty, so to speak, but I’ve got to put it back on and be sure I put it back on appropriately.

BPE: Can that gear be sanitized between uses?

Dr. Sovndal: It can, and there are different techniques. You can use heat, aerosolized chemicals, and UV light. Our hospital is currently using UV light for cleaning our equipment, so you turn in your mask at the end of your shift, and they return it to you the next day, after it’s been cleaned.

BPE: Continuing with this subject, I wanted to ask you about cleaning up at the end of a shift. Are you showering before you leave the hospital?

Dr. Sovndal: My process is this: I come into work in civilian clothes. Then, I put on my scrubs and my shoes. All that stuff stays at the hospital. I put my protective equipment over top of my scrubs.

After I put on that protective gear, I leave that on. I try never to touch my face during my whole shift, because that’s the most risky piece of it. When I’m done with my shift, the PPE comes off, the scrubs go into the laundry basket, I put my civilian clothes on, I come home and take those off in the garage, and then I walk directly into my shower and shower off. It’s a double-tiered system.

BPE: You’re basically doing everything you can?

Dr. Sovndal: Yeah. I have a 3-year-old and a 1-year-old, and that’s concerning. People say kids are okay, or that kids have complications at a lesser rate. But children still get very sick from this. So we see kids, just like when they get really ill from the flu, and that’s the same that’s true for this. There are complications that kids have, so it’s definitely a concern.

BPE: If kids are okay, as a blanket statement, they wouldn’t have closed schools, I assume.

Dr. Sovndal: Yeah. Part of that is, they still catch it, and they’re great spreaders and carriers of any virus, really. So part of it is to keep them from spreading it to their families.

BPE: What about protective gear for the general population?

Dr. Sovndal: We definitely have a shortage of protective equipment in the community, so it is recommended that we practice social distancing. It is also recommended that you wear a mask in public, and I absolutely support that. But the level of masks that you’re supposed to wear in public is a surgical grade mask, which is a droplet protection mask. Many people are just using a cloth mask, which really doesn’t do the trick, because, if you sneeze or cough, a lot of particles go right through that cotton.

I’ve partnered with a company here in Boulder – Scratch Labs – that makes sports energy drinks. We just put out a free video and PDF on how to make a functional surgical mask. If you can’t make one, you can get one in a couple of days by just writing to Scratch Labs.

BPE: Do you have any opinion on the suggested use of these anti-malaria drugs, such as Hydroxychloroquine?

Dr. Sovndal: We need more data. I think that normal doctor approaches apply here; there is officially no medicine that’s for free. What I mean by that is, every time you give someone some medicine, there is a potential downside to that medicine. There are side effects; people can have bad reactions, or it can interact with other medications that they’re taking.

So, there’s no magic pill out there really.

What we are concerned about is that, in theory, it might work But really, when we’re going to distribute medicine to a lot of people, that side effect profile becomes a real risk. If I give 1,000 people this drug, there’s a real potential that one of those people will have a really bad outcome, simply because they got the drug.

We just need to be sure. Trials are underway, but I don’t think we have the data yet. I would certainly be interested in reading the early results of the trials, but what we’re basing it on so far is conjecture, which is a really weak form of evidence. When you’re a physician, you’ve got to first believe in the adage to, ‘Do No Harm’. You have to believe you are not doing any harm, when you are giving somebody this medicine.

BPE: This may be anecdotal, but I’ve been told the Army used to give this cocktail to the troops in Vietnam as an anti-malaria tonic. The grunts in the field reported mixed results. There is also some research indicating psychological problems associated with this class of drug – enough so that the Army stopped giving it to Special Forces units.

Dr. Sovndal: For sure. I’ve traveled in areas of Africa where you need to take those sorts of medicines. And if you really research that drug when deciding what malaria medicine you should take, you’ll find why I didn’t take it. I took a different malaria medicine. It’s interesting that it does have enough of a profile that, in peaceful times, I’m making decisions about what medicine I want and whether I want to take that particular medicine.

BPE: What are citizens in your area doing to support healthcare workers and first responders?

Dr. Sovndal: I will say that a couple of very positive things have come from this crisis. The first is that hospital teams feel quite cohesive. I’m seeing a very strong team unity and approach to this pandemic. It is a mind set that we’re going into battle, and we’ve really rallied to protect and take care of each other. I feel that’s the first step.

And then, there is the outreach from friends and family in the community who know that you’re a healthcare provider. I’m constantly getting messages that say, “Thanks for doing this,” “Thanks for keeping the fight,” “You’re doing a good job.” And then, you see signs put up near the hospital that say, “Thanks, First Responders,” with hearts written on them.

Some people have put up Christmas lights. We have a Santa Claus with a Covid mask near the hospital that says, “Strong Work, First Responders.”

From our community standpoint, we’ve been overwhelmed by the amount of food that they provide us at the hospital. Every shift that I go on, we have multiple local restaurants furnishing high-end meals.

As a side note, it’s funny, because even with all that delicious food, it’s my practice to not take my protective equipment off to eat. So, I suffer through my shift, meaning I hydrate as I am able and eat when I am done for the night.

BPE: Can you talk for a minute about PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) with doctors, nurses, and first responders?

Dr. Sovndal: We usually think about the military veterans succumbing to PTSD, but first responders really suffer from PTSD and depression as well. The rate is two times the normal populations for PTSD in first responders.

Twelve to 15% of male doctors have depression. Twenty percent of all female doctors have depression. If you look at that stat, compared to suicide in the general population, doctors have a very high rate of successful suicide. When a physician decides to commit suicide, the rate is almost double that they will be successful in completing the task.

BPE: With all of this justifiable doom and gloom, are you seeing any positive signs?

Dr. Sovndal: The positive things, I would say, is what I told you about the community – about our team in the hospital; the connection I feel, and how proud I am to work with them.

BPE: You wrote about this sense of connection in your new book, Fragile. Could you tell us about your book?

Dr. Sovndal: Yes, Fragile deals with the very themes we are talking about here. Obviously, I never thought that something which was written over the course of 8 years, with a planned release date that was set a year ago, would be coming out during a Pandemic. But what Fragile addresses is how everything that we feel in life is so fragile.

Our lives were so different a month ago. All of a sudden, our whole world has been turned upside down. That’s what we’re talking about, when we say that life is fragile. That may sound like a book of gloom, but really it’s a book of resiliency.

What does that mean when life is fragile?

For me, as a physician, I’ve struggled with death and dying – and all the stresses – for a lot of years. But I have slowly come to this realization that life is a spectrum. There’s no way that you can avoid the bad; there’s no way you can automatically get to the good. It’s just life, and we are constantly moving forward.

You really need the whole spectrum, in order to experience all the things that you want.

My wife and my kids? My happy home? I wouldn’t have that, if I didn’t realize that life is fragile.

If I didn’t see people die; if I didn’t see disease; if I didn’t see any of these things happen, there’s no way that I could feel as connected as I do to the things that I cherish most.

That point is really what the cycle of life is, because we see these fragile things. These terrible events happen, and they are terrible. But it’s a decision to come out the other side. How do we look at that whole picture, and how does that affect us?

BPE: Experiencing tragedy gives you a real appreciation for the positives in life?

Dr. Sovndal: Yes, it does. And it’s so interesting, because I wrote the book from the standpoint of being a physician. But right now, almost everybody is having that experience. Right? Everybody who is having this experience is going to relate to this idea, because their life has been turned upside down.

BPE: If you go back to the Spanish Flu of 1918-1920, that’s probably the last event of this nature to turn the world upside down. The survivors of that era are the children who also lived through the Great Depression and World War II. They’re all getting up in age now, but again, you’ve got that commonality. Everyone of them you meet has a story that’s related to everybody else’s story.

Dr. Sovndal: Yes, exactly. It creates a level of connection, which is really what life is all about.

We have so many ‘whys.’ Why is this happening; why is there this pandemic? That’s to be expected, but I feel we’re asking the wrong questions. The whys will always be happening. We have to ask two different questions:

1) What is my why? Why do I feel like these things are important?

2) What is the who in my life? Who are the people that I’m connected to and want to be with?

Considering these two key questions can ease the confusion and the craziness of all these whys blowing out of control. They help us to really hone in and say to ourselves, ‘Oh, I see some sense in all of this’.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”