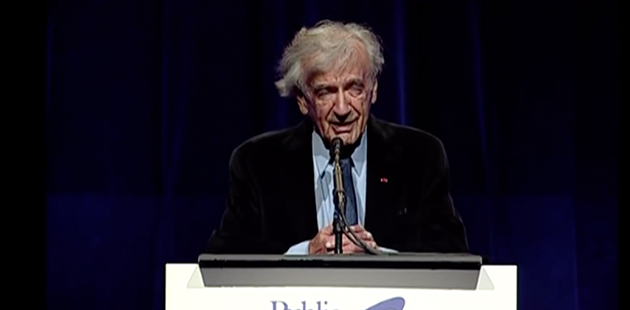

Elie Wiesel remembered

I was fortunate enough to have had the opportunity to meet and briefly speak with Holocaust survivor and 1986 Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel in 2005 when he gave a lecture at McDaniel College in Westminster, Maryland.

Prior to the lecture, Wiesel met with students and faculty in the common area. It was there that I expressed my admiration for his work and asked Wiesel to sign a copy of his 1960 English-translated masterpiece Night, which eloquently chronicles the horrific experiences he endured at Auschwitz and later Buchenwald. Wiesel thanked me for the compliment and graciously signed the book. It remains one of my most prized possessions.

Having visited Auschwitz several years earlier and subsequently exploring what remains of the extermination camp turned-state museum where 1.1 million were murdered, I already had a strong appreciation for what Wiesel endured while imprisoned there. That Wiesel survived to bear witness to a place where most prisoners, including his mother and youngest sister, were gassed upon arrival is a testament to his indomitable will to survive.

Few could have so eloquently characterized the sheer insanity of Nazi terror as Wiesel did in Night when describing the atrocities witnessed during his first night at Auschwitz.

“Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky.”

But perhaps Wiesel’s most poignant and personally heartbreaking depiction in Night surrounds the events leading up to the death of his father, who survived a lengthy death march before ultimately succumbing to disease and starvation in late-January 1945 shortly after arriving at Buchenwald.

“I woke from my apathy just at the moment when two men came up to my father. I threw myself on top of his body. He was cold. I slapped him. I rubbed his hands, crying: Father! Father! Wake up. They’re trying to throw you out of the carriage … His body remained inert … I set to work to slap him as hard as I could. After a moment my father’s eyelids moved slightly over his glazed eyes. He was breathing weakly. ‘You see’, I cried. The two men moved away.”

Wiesel wrote more than forty books, most of which primarily focused on the Holocaust and perceptions of Jewish identity. But his vocal activism on behalf of the persecuted knew no racial, religious or ethnic boundaries. Wiesel’s visceral condemnation of South African Apartheid, genocidal acts committed by Cambodian dictator Pol Pot and then-Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, are just a few examples.

That premise is perhaps best summarized in Wiesel’s 1993 Passover Haggadah.

“At critical times, at moments of peril, no one has the right to abstain, to be prudent. When the life or death or simply the well-being of a community is at stake, neutrality is criminal, for it aids and abets the oppressor and not his victim.”

Wiesel died Saturday at age 87.

Bryan is the managing editor of Baltimore Post-Examiner.

He is an award-winning political journalist who has extensive experience covering Congress and Maryland state government. His work includes coverage of the first election of President Donald Trump, the confirmation hearings of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh and attorneys general William Barr and Jeff Sessions, the Maryland General Assembly, Gov. Larry Hogan, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bryan has broken stories involving athletic and sexual assault scandals with the Baltimore Post-Examiner.

His original UMBC investigation gained international attention, was featured in People Magazine and he was interviewed by ABC’s “Good Morning America” and local radio stations. Bryan broke subsequent stories documenting UMBC’s omission of a sexual assault on their daily crime log and a federal investigation related to the university’s handling of an alleged sexual assault.