Edgar Allan Poe still alive and well in Baltimore (Part One)

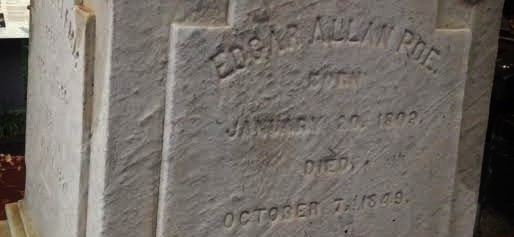

Weathered etchings on Edgar Allan Poe’s grave (Lauren Molander)

The first of a two-part interview with Poe scholar Richard Kopley

Few names carry as much cultural weight as Edgar Allan Poe in Baltimore. References to the 19th Century writer are found all over the city, from historical sites from his life and death, to local beers, to the name of our beloved NFL team (his face even made the list of recently released, Baltimore-themed emojies). Poe is a treasured part of our city’s identity- a gloomy mascot, tingling with mystery.

In light of the 166th anniversary of Poe’s death on October 7, the Baltimore Post-Examiner had an opportunity to speak with a leading Poe scholar about his studies on the author’s life, Poe’s innovative career and the reasons for our enduring obsession with him.

Richard Kopley, Ph.D., a longtime resident of State College, Pa., was a professor of English at Penn State DuBois for 31 years. Though he recently retired, Kopley has kept busy with scholarly essays on celebrated writers, a few book projects, and much more. He is also active in organizations such as the Poe Studies Association and the Nathaniel Hawthorne Society, both of which he’s served as president of in the past.

While his literary expertise stretches widely, Poe in particular has kept a powerful hold on his interest as a scholar and a reader. He’s even collected artifacts from Poe’s life, such as a bit of his wife’s wedding dress (now on loan for a special exhibit at the Poe Museum in Richmond).

In Part One of our two-part interview, Kopley shares some ideas about what Poe and his work mean to him, Poe’s place in the literary world during his lifetime, some of the intriguing possible inspirations behind his writing and more.

BPE: Edgar Allan Poe has been the focus of so much of your work. When did you first become interested in the author?

RK: I was a grad student in the ’70s at SUNY Buffalo. I was working with [literary critic] Leslie Fiedler, reading books he’d covered in his own book, Love and Death in the American Novel. One book that caught my attention more than any others was a book I’d never heard of- a novel by Edgar Allan Poe called The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. I wrote a seminar paper on it, and I decided to continue studying it. In fact, it became the subject of my dissertation. I graduated in ’82, but I made more discoveries about Pym after that, as I kept writing about it.

So, that’s how it all started for me, with that novel.

BPE: What was it about Pym that grabbed you?

RK: It was the ending. It’s a nautical novel, and as the novel continues it gets more and more strange and mysterious until the final paragraph, which is so strange that it was removed in the British edition of the book for being too unbelievable.

The ending is a visionary moment when the main character, in the South Seas heading towards the South Pole, sees “a shrouded human figure, very far larger in its proportions than any dweller among men,” with skin that’s “the perfect whiteness of the snow,” and [except for a closing note] that’s the end of the story. That’s it.

It seemed to me that on one hand, it was a vision of divinity. But, on the other hand, I thought there was something specific going on that you could work out if you tried. Because, after all, Poe is the guy who invented the detective story. He wouldn’t create a mystery without a solution. And slowly but surely, I figured it out. It took me nine years.

In addition to his work with “Pym,” Kopley has written extensively about Poe’s other works. In his book, “Edgar Allan Poe and the Dupin Mysteries,” he explores some possible real-life inspirations behind Poe’s three short stories featuring detective C. Auguste Dupin.

RK: After Pym, I was studying “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” [the first of the three stories]. After that, I thought I was through with detective stories. But years later, in a Connecticut bookstore Whitlock Farms, I found a source for another of the Dupin stories, “The Purloined Letter.” I realized that if I could find something new in the remaining story, “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” I’d have a book.

I made discoveries specific to each story, but there is an underlying element to each of them involving a woman of an uncertain reputation, a woman whom people aren’t quite sure about. I think that what Poe was dealing with was his own mother. She died when he wasn’t yet three, but as he grew up he certainly would’ve heard what people were saying about her. See, her husband, Poe’s father, left 12 months before Poe’s sister was born.

Poe had to have known that there were questions about his mother, and it would’ve been very upsetting to him. He would’ve felt stuck- how could he prove that his mother was innocent? It was only in the third Dupin story, “The Purloined Letter,” that Poe’s detective was able to save the woman. I think that was the point of these stories all along, to protect his mother in fiction as he couldn’t in life. His mother is critical to understanding the stories.

I enjoyed working with the Dupin stories very much.

BPE: Aside from the mystery in his own life, what else do you think might have inspired “the father of the modern detective genre” to create these kinds of stories?

RK: In a way, I think that Poe wanted to write about how to read. He published Pym in 1838, and as far as I can tell from reading the critical and popular reception, nobody actually, fully understood the novel. He would’ve been interested in helping people to consider ways of reading beyond just, “what happens next?” That might’ve been part of his motive in creating these stories. The detective is really a reader. If we would follow, as readers, the methods of Poe’s detective, we’d make more headway in our reading of the stories.

Also, he wanted to write something that would be successful and well-received, and there was indeed a fascination inspired by Dupin, who eventually became Sherlock Holmes and every other detective that we know. Here Poe achieved what he was looking to achieve.

I don’t know if he understood that he had created a genre, but as we know, he had.

BPE: During his lifetime, where did Poe rank among other American writers? Was he recognized internationally?

RK: I would say he was one of the top three American writers at the time, the others being Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville, and they’ve all endured. Poe’s work was translated into French in his lifetime, so there was some international recognition, but most of that took place after his death. He eventually became known in every language.

It’s a connection we often have, as Americans, with the people we meet abroad. We all know Poe. He, Mark Twain and Ernest Hemingway are probably the three American writers who are most well-known, abroad.

BPE: Of all of Poe’s works that you’ve studied, was there any that didn’t live up to your expectations? A least favorite?

RK: Oh, dear. I’m not a big fan of his [unfinished] novel, The Journal of Julius Rodman. I don’t think he particularly cared for it himself- he stopped writing it in the middle! On the other hand, anything he wrote is interesting, even if it’s not his most successful work. It’s interesting because he wrote it. So, that’s a hard question to answer.

In Part Two of our interview, Richard Kopley discusses Poe’s complicated journey to Baltimore, his life in the city (as well as his mysterious death), and some of the reasons for our lasting fixation on the Master of Mystery in Baltimore and beyond.

Lauren Molander, a Baltimore native, is on a long-winded journey to find her place in the world. She majored in Media and Communications Studies at UMBC, and hopes to build a career working with words.

Lauren is unusually enthusiastic about roller coasters, SNL, fancy teas, cosplay culture and the broody music of her early teenage years. In her free time, she can be found playing with makeup, beating the same video games repeatedly, begging her cats for affection, reading books by funny people and binging on anime.

She is still waiting patiently for her (tragically delayed) letter from Hogwarts.