How to change Baltimore’s neighborhoods: Make renters stakeholders

I remember riding around Baltimore with my father when I was a little kid. He would give me the history of Baltimore neighborhoods from his childhood up until that present. Both he and my Mother were old school. They didn’t like highways or expressways. We always drove through the city.

So on our daily journeys from East Baltimore to Roland Park for school, we would sometimes ride up North Avenue or venture through Mount Vernon and what’s now Station North. Even as a kid when you saw the architecture, you knew you were looking at the remnants of something special and gorgeous – these were places that were once cared for.

It always amazed me how in three to four decades a thriving neighborhood could become a crack infested ghetto.

What happened?

The rise of suburbs and white flight happened. The Riots of the late 1960s happened. Inner-cities became forsaken wastelands of forsaken people. And then crack happened.

In the days of yester year, there was an omnipresent feeling of community pride in this city. You scrubbed your stoop on weekends and chastised litterers. This was the neighborhood mindset because residents were stakeholders in the place they lived.

Over the past 30 to 40 years, residents stop being stakeholders in their neighborhoods. People were just living in a place for an unknown period of time – with no real ties to their home or the residents who lived next to them.

Well at least that’s what my Daddy said and Presidents Clinton and the younger Bush agreed with him. Remember all the tax incentives and lax regulation regarding housing of the 1990s and the 2000s? A lot of this was done to spur homeownership. The government attempted to make more stakeholders in order to strengthen American communities.

But a funny thing happened on the way to a Great Recession; we learned that everybody shouldn’t own a home. Presently, many Americans are ill-equipped and/or ill-qualified to buy a home. However, especially in Baltimore, we still need more stakeholders in our neighborhoods to create and maintain the stability needed to keep them a float or turn them around.

Renters are being priced out of the market

If you can’t increase the number of homeowners, presumably you’d like to turn to responsible well-established renters to become stakeholders in their communities. But there’s a problem with that logic. Many renters are being priced out of the Baltimore market.

This is a national phenomenon. RealtyTrac now reports that a third of Americans now live in housing markets where rent for a three-bedroom home consumes more than 30 percent of their monthly median income – the 30 percent threshold for years has been the benchmark for rental affordability.

Many cities such as Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Miami and yes our own Baltimore are trending toward residents paying almost 50 percent of their income towards rent.

Many cities such as Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Miami and yes our own Baltimore are trending toward residents paying almost 50 percent of their income towards rent.

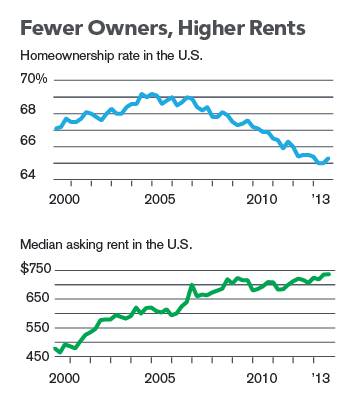

The housing collapse forced millions of former homeowners to become renters, according to Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. Stan Humphries, the chief economist of Zillow said that between 2007 and 2013 the United States added, on net, about 6.2 million tenants, compared with 208,000 homeowners.

The glut in demand for rentals was the catalyst for raising rents more than 21% higher over this same time period. It becomes clear that many can’t afford to stay in the city leaving Baltimore a place with an extreme case of haves and have-nots: stakeholders and non-stakeholders.

For this city to solve many of its major problems, this trend cannot continue. If everyone can’t own a house, you have to come up with other ways to create stakeholders in Baltimore communities.

One innovative idea to create stakeholders is going on right now in Cincinnati.

Cornerstone Corporation for Shared Equity’s renter equity program

Back in 2000, the Cornerstone Corporation for Shared Equity (CCSE) nonprofit community development organization created an innovative spin on the renter/property manager dynamic.

Renters in CCSE owned and developed properties enter into a renter equity contract where they earn “equity credit” when they fulfill specific obligations listed in their rental agreement. These commitments can range from work assignments on the property, paying your rent on time or participating in resident meetings.

CCSE residents can earn up to $4,137 in equity credit after their first five years and become 100% vested in the Cornerstone Renter Equity fund. Renters would max out at $10,000 at the end of 10 years.

When residents hit this important five year mark, they can cash in their credits for whatever their heart desires. There are also loan provisions where they can borrow against credits earned – reminds me of what would happened if you borrowed from your 401(k).

Now it was at this point I wondered why anyone managing property would adopt a system where you give money away to residents. Well, there are two reasons.

First, the renter equity system is supported by management and development fees in conjunction with foundation support.

Second, the partnership has translated into average occupancy rates of 96% minimizing turnover costs for CCSE. And property-management costs seem to be on par with similar Low-Income Housing Tax Credit properties in Cincinnati

From all accounts, it seems to be working.

Last year a study by the Ohio Housing Finance Agency took an in-depth look at CCSE and found that there system created a Win/Win solution for the residents and their broader community. Through the system, rents are kept affordable while CCSE has long-term tenant occupancy.

The report documents Cornerstone’s success from 2002 and 2012 in “building residents’ wealth, sense of well being and the maintenance of the property”. In short, the experiment gives a proven option to explore between the renter and property manager relationship which could be applicable to changing or maintaining some troubled Baltimore neighborhoods.

Renter equity systems would not be for everyone or every neighborhood. However, it could possibly bring back an appreciation for the architecture and craftsmanship that originally went into the making of the house you live in. It could build up even more courage to fight against the crime and violence that may be prevalent on your block. It could also shed a little light on a future that may have seemed cloudy.

For years we’ve tried developing more buildings in certain areas to make a better Baltimore. It’s time we developed some more stakeholders in other areas and see where that gets us.

Jason spent eight years at T. Rowe Price serving in various roles from investment counseling to retirement planning. In 2005, he became Senior Security Analyst at Wells Fargo Corporate Trust in their Residential Mortgage-backed Securities division. He has contributed to several financial newsletters and the Motley Fool website while completing his thesis and Master’s Degree in Government from the Johns Hopkins University Advanced Academic Program. He resides in Baltimore.