‘In My Life’ all these places have their moments and John McNamara loved them all

BALTIMORE — When I heard the horrific news that five people had been shot at the Capital Gazette newspaper, I immediately thought of John McNamara. Surely, Mac would convey the massacre in all its agonizing detail, I thought, as I frantically sought witnesses while stringing on the story for The New York Times. I remembered him as a newspaperman extraordinaire, a reporter’s reporter, with a great eye for detail, a strong ear for a good quote and the Irish gift for putting words around it all just so.

I sent Mac a Facebook message before anyone had been confirmed dead in the newsroom at the Annapolis newspaper where he worked as an award-winning sportswriter and news editor. I had no idea I had just written to a man who lay dead at his desk, along with four colleagues, shot down by a hate-filled, deeply disturbed man with a grudge against the newspaper for its reporting how he had terrorized a long-ago high school classmate.

It had been years since I had seen Mac, but I had followed his sports writing and read his richly detailed, panoramic books about the legendary Terps football and basketball programs. In the hurry up and wait for a big, breaking story, my mind meanders through the decades. Mac had been a friend and mentor when I arrived at the University of Maryland’s daily newspaper, The Diamondback, as a cub reporter in the magical spring of 1982. A time of innocence, a time of confidences, when the horizon of possibilities seemed eternal.

I had been assigned to cover a daylong energy conference at UM’s adult education center. I recorded it all — and I cried while trying to make sense of it. I wrote the story out longhand and typed it into the new “video-display terminals,” among the first at a college newspaper in America. I filed a lead something like: “U.S. Energy Secretary James Edwards, utility officials and other energy experts gathered Saturday at the conference center at University College to discuss the complexities of America’s energy crisis.”

Mac asked me to sit down. “This is called a label lead,” he said softly, with his baby-faced leprechaun smile. “That means you could have written it before the event even happened. Focus instead on what happened, what’s new, what’s news.”

Then he started typing: “U.S. Energy Secretary James Edwards, speaking at a conference at University College Saturday, said the energy crisis has been overblown.”

Mac — still sweating from sinking his deadeye, three-point lefty shots in hoops, as he did often — then patted me on the back, and said: “Don’t worry about it, kid. Every cub makes this mistake. Now you won’t anymore.”

That’s how John McNamara taught — gently, wisely, with compassion and grace, at a student newspaper that prided itself on comforting the afflicted, afflicting the comfortable, where the editor in chief who helped groom Mac, David Simon (of “Homicide,” “The Corner” and “The Wire” fame), would write: “The journalist is the kid who stood at the edge of the playground, plotting his revenge.” Lots of us assorted misfits and malcontents who found our refuge in the Diamondback newsroom, atop a dining hall on the southern edge of the sprawling College Park campus, must have stood at the edge of some playground — young, full of idealism; our revenge, the revenge against the powerful, the mighty, the comfortable who, unchecked, would trample the rights of the afflicted, the powerless, the downtrodden.

Another Diamondback alum, the painfully shy Gerald Fischman, also killed at the Capital Gazette, showed up at the Diamondback newsroom in 1977 in a tie, dress shoes and a cardigan sweater. Fischman covered the College Park City Council with a passion few could fathom and went on to write incisive, sometimes blistering, but always meticulously researched and well-reasoned editorials for the Capital Gazette.

I never met Gerald Fischman, but I felt like I knew him from the stories handed down, from his pieces in the yellowing pages of the Diamondback’s bound volumes, from a few choice quotes and scenes typed on the back of Associated Press and United Press International wire machine copy paper and pasted on The Wall in the newsroom of the college daily.

Neither Mac nor Fischman nor legions of other Diamondback alum in that newsroom cauldron on the third floor of the South Campus Dining Hall building could imagine a higher calling in life than serving as a journalist.

Nor could any of us have conceived then of an America where a Tweeter-in-Chief of a president condemns the Fourth Estate regularly as the “enemy of the people,” where alt-right commentators and extremist groups call for the assassination of journalists, where a Capital Gazette column exposing Jarrod W. Ramos’s criminal harassment and stalking of a former high school classmate would prompt him to shoot up a newsroom on a sunny Thursday afternoon. No law enforcement official suggests any motive in the shooting beyond a vendetta against the newspaper, an Annapolis institution — the Crab Wrapper, the Crapital (everybody bitches about it, and everybody reads it every day, without fail). But the shooter’s record of Twitter posts shows he had links to and staunchly supported alt-right figures who espouse, among other things, killing journalists.

Of course, most sane people in America almost universally rallied behind journalists after the mass shooting. Gratifying, perhaps, as we in the press don’t get a whole lot of love and praise these days — or, in any age, for that matter — if we’re doing our jobs right.

A fellow Diamondback alum shared with me the five victims’ names, on background, and confirmation came quickly from there.

An order, not a suggestion, came from The New York Times National Desk: Do not contact relatives until we know with absolute certainty they have been notified by the authorities. I would learn only weeks later how much of the media did not follow that tenet of journalism and basic humanity, when McNamara’s widowed bride, college sweetheart and fellow Diamondback alum, Andrea Chamblee, wrote of getting the calls from reporters, before she had any idea her husband had been shot: Do you have a statement? the reporters asked. Of all the coverage and all the accounts I read and heard about this massacre, The Washington Post essay by Chamblee, now a Food & Drug Administration attorney, on the aftermath and its toll on her shattered life — the story no one else in the world could tell — will stay with me always. It is at once raw, riveting, heartbreaking.

I did not mourn for Mac or the others right away. Big breaking stories, as Mac would agree, leave no time for the luxury of indulging emotions. There’s a story to tell. For two days and well into the nights, I kept moving, running on caffeine and nicotine and the adrenaline buzz, in and around Annapolis. A prosecutor says at Ramos’s initial court appearance that he really did barricade the back newsroom entrance to prevent victims from escaping.

I file feed after feed to Times National Correspondent Sabrina Tavernise, a force of nature who works a story as few I have ever seen, and to editors on the National Desk. Of all the international saturation coverage immediately following Ramos’s rampage, Tavernise finds the scene that sticks with me most: She’s interviewing Capital Gazette photographer Joshua McKerrow as he and colleagues put out the next day’s edition, working on laptops, from the back of a pickup truck in the parking garage of Westfield Annapolis Mall, hours after the shootings.

McKerrow cries, but not before he files his photos for the paper. Because that is what we do.

After sending the last email to Tavernise Friday night, I can’t turn it off, or stop reading about it or watching the videos. Until I think of the quote I found on Mac’s Facebook page the previous day when I still thought I was preparing to interview him: “Are we not all precious in God’s eyes?” (He had posted it, Andrea tells me, after they saw “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” — the Mister Rogers movie.)

With that, I break down, and the illusion of the hard-bitten newspaperman of the past two days crumbles. I weep. For Mac, for his wife, for his colleagues, for all of us. For they are us, and we are them, but for grace and circumstance.

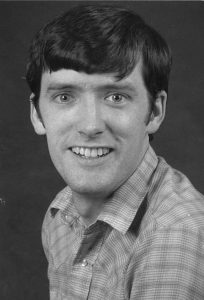

At Mac’s service at UM’s chapel about two weeks later, “In My Life” plays, and oversized images of his life flash across the video screen.

His wife tells me how much Mac had savored the simple joys in life. The good Jesuits call this finding God in all things, and they urge we serve as men and women for others. John, Chamblee says, always looked for the good in everyone and everything. Amid the noise and the haste, he would repair to the porch on summer’s nights, listen to the Washington Nationals baseball games on the radio, and to see him there, she remembers, was to see perhaps perfect contentment.

Somebody at the Diamondback — the de facto journalism college back then — said something else that has stuck with me through the decades: As journalists, we must be mirrors on reality – and, in these dark days — perhaps by showing America its reflection, we will shine a light that ultimately helps end this madness.

For now, I dry my eyes, and drink a Guinness to John McNamara, to his four fallen colleagues, to the Capital Gazette, to the Diamondback then and now, to the Fourth Estate, to us all.

I leave the chapel right after the service to get to an assignment. On my way out, I ask John McNamara – fellow Catholic, fellow Irishman, fellow newspaperman — to take a break from filing whatever story he’s filing in heaven and to pray for us.

We, the press, and the divided nation we serve, awash in hatred and violence, need it now more than ever.

Gary Gately, a seasoned journalist, has won 15 national, regional and local awards for reporting and writing news, investigative, public service, feature, business and travel pieces. Gately’s work has been published by The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Baltimore Sun (where he worked in reporting and editing jobs for 11 years), Baltimore Examiner, the Chicago Tribune, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Guardian, The Washington Post, The Dallas Morning News, Business Week, Newsweek, Arrive Magazine, The Center for Public Integrity, CBSNews.com, CNBC.com, ABCNews.com, USAToday.com, HealthDay, The Crime Report, United Press International and numerous other newspapers, websites and magazines.

His coverage has received awards from the Associated Press, the Society of Professional Journalists, the Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild, the Maryland-Delaware-D.C. Press Association and the Society of American Travel Writers (first-place Lowell Thomas Award for best newspaper travel story/U.S.-Canada (immigrant New York).

Gately also has extensive experience editing for newspapers and websites, has taught college journalism courses in news writing, magazine writing and travel writing and is the author of Maryland: Anthem to Innovation, a book on the state’s history, industries and attractions.