What does Gov. Scott Walker’s recall victory in Wisconsin really mean?

Whoa, all you political Cassandras, those of you who see the sound defeat to recall Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker as the End Time for unions and a harbinger of things to come in November’s Presidential election.

Before you join the Trojan rout, let’s dissect the entrails. First, let’s drop the classical and apply a sports metaphor to the Wisconsin situation to better understand it.

What would it mean if the New York Yankees beat the Milwaukee Brewers in the World Series? (Don’t worry how the Brewers got there. Go with it.) Certainly, it would be a Yankee win, but the Yankees outspend every other team to get its pennants. Dollar power for talent.

And Walker outspent his Democratic opponent, Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett, big time.

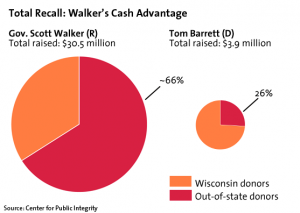

Walker’s fundraising was nearly 10 to one compared to Barrett’s.

He raised $30.5 million, according to Center for Public Integrity, and had laid out $45.6 million by the May 29 filing date, the New York Times reported. Two-thirds of his money came from deep pocket ‘independent” sources outside the state and others like $9 million on ads from the Republican Governor’s Association Right Direction Wisconsin PAC, of which $7,000 has been raised in Wisconsin.

He raised $30.5 million, according to Center for Public Integrity, and had laid out $45.6 million by the May 29 filing date, the New York Times reported. Two-thirds of his money came from deep pocket ‘independent” sources outside the state and others like $9 million on ads from the Republican Governor’s Association Right Direction Wisconsin PAC, of which $7,000 has been raised in Wisconsin.

In contrast, Barrett raised $4 million, 80 percent that from inside the state, but. Because of a peculiarity in the state’s campaign finance laws, he was legally barred from taking “independent” contributions, mostly from union groups, in excess of $10,000. His total expenditure: $17 million.

Walker’s financial tsunami swamped Barrett’s buoy, but it’s hardly a precursor of things to come.

It is more like a replay of history: Walker’s 2010 win over Barrett for governorship. Nineteen months later, the same two candidates line up toe-to-toe and the statistics barely shift.

By the same margins, Walker again bested Barrett with men, most Republicans, those without college degrees, people over 30, independents, and rural and suburban voters. He lost women, voters under 30, moderates, college graduates, lower-income voters and urban voters, and, not surprisingly, most Democrats.

On the issue that started the recall– Walker’s bridging the state’s budget shortfall (attributed to the state legislatures $67 million two-year tax cuts and deductions for businesses) by slashing public employees salaries and trying to take away their collective bargaining rights–he picked up about the same number of Republican union households (38 percent) that he did in the gubernatorial race (37 percent).

Does it mean that Wisconsin, the first state in the United States to provide collective bargaining rights to public employees in 1959, has abandoned its legacy of progressive socialism?

If so, then how to account for the 20 percent of Walker voters – and the 51 percent of voters in the exit poll –who still maintain a favorable opinion of public employees. Fewer Americans are union members in the private sector than in the past and more in the public, but a slim majority of Americans still recognize that you can’t negotiate with the boss by just saying “please.”

In one quirk of the exit polls, there was a lot of partisan crossover with the same voters who supported Walker, saying, by 51 percent to 44 percent, that they favored the re-election of Democratic President Barack Obama over Republican Mitt Romney for president.

For some inexplicable reason, Obama kept a low profile during the recall dust-up, tweeting his support for Barrett instead of making a flying visit and personally campaigning around a state that is among a dozen that are expected to be battlegrounds come November.

Perhaps he was counting on Wisconsin to stay blue since it hasn’t voted Republican since Ronald Reagan in 1984. Or maybe he’s hoping for a replay of his 2008 win — a 14-point margin.

Both sides are calling Walker’s victory the way they want it to be.

The Republicans see it as a sign that a Republican will be in the White House come November.

The Democrats say a state recall, which wasn’t popular with most of the electorate, isn’t the presidential contest. In other words, it’s a long way to the World Series.

But both sides might want to read Michael Lewis’ “Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game” –which argues that the statistical approach to assessing baseball players didn’t mean a thing when the Oakland A’s started using more analytical measurements.

It’s a new day gentlemen. All bets are off.

Karen DeWitt has a long distinguished career as a journalist, covering politics, but also has worked on political campaigns. She compares the later to the labor of a Hebrew working for the Pharaoh. She’s covered the White House and the national politics for The New York Times; foreign affairs and the White House for USA TODAY before joining that newspaper’s management as an assistant managing editor. She switched to television as a senior producer for ABC’s Nightline, where she wrote and produced the award-winning, Found Voices about the digitization of 1930s and 1940s interviews with former slaves. She returned to newspapers, as Washington editor for the Examiner newspaper and eventually left to help on local political campaigns. She has several blogs, but contributes mostly to a food blog called “I don’t speak cuisine” at peacecorpsworldwide.org and theroot.com.