The Widow Bixby: Figuring out the legacy of the Civil War’s most famous mother

Lydia Bixby and Abraham Lincoln

Introduction

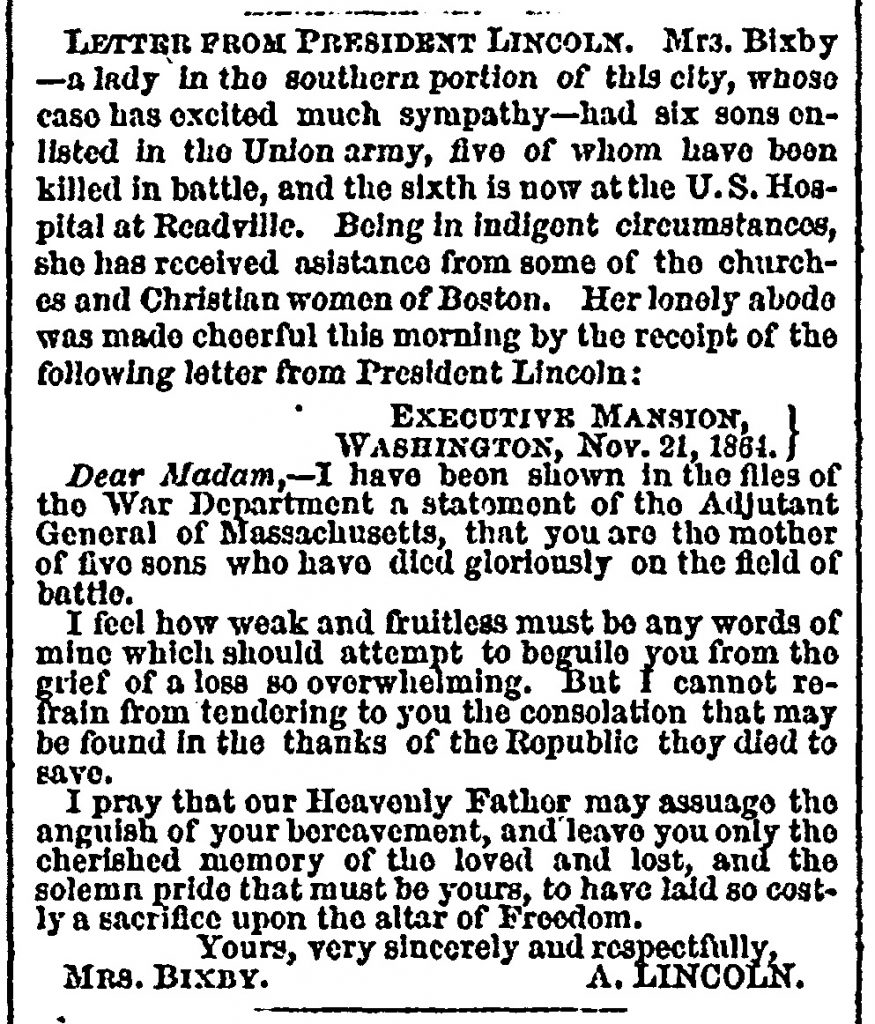

Executive Mansion,

Washington, Nov. 21, 1864.

Dear Madam,

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle.

I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering to you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save.

I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of Freedom.

Yours, very sincerely and respectfully,

A. Lincoln.

A short, sincere note from Abraham Lincoln to the widow Lydia Bixby, of Boston, upon the Governor of Massachusetts’ suggestion that he offer his condolences for the loss of her five sons in the Civil War, may have been all this letter was. However, it has since entered an important place in history-one source calling it a “masterpiece of the English language”-for its symbolism of the American spirit and self-sacrifice of ordinary citizens in the times of national struggle.

The letter received Hollywood attention in the movie Saving Private Ryan (1998), in which a fictional version of Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall reads the Bixby letter to his subordinates to justify a dangerous rescue mission in post-D-Day Normandy of a young paratrooper who had unknowingly lost three older brothers in the days prior. Interestingly, there have been many reports of Mrs. Bixby having six sons who went to war, five of whom were killed. According to The Pictorial Book of Anecdotes and Incidents of the War of the Rebellion (1873): “A sixth son, who was wounded in one of the then-recent battles, and who belonged to a Massachusetts regiment, was lying ill in one of the hospitals,” and a December 1864, article in The Boston Liberator stated that: “It appears that she [Mrs. Bixby] has also sent another son to the war, who is now suffering from wounds at the United States General Hospital at Readville.” Was there a Saving Private Bixby story to return this soldier to his grieving mother? Unfortunately, also fascinatingly, the story of the Bixby family is far more complicated than it would first appear.

A number of historical researchers published their own take on the Bixby letter and family, primarily in the early 20th century. One of the most significant finds of the case of the Bixby family is that Lydia Bixby did not lose five sons in the war-the popular conclusion now being that, of these five, two were killed, two deserted-one possibly to the Confederate Army-, and one was honorably discharged at the end of his service.

Mrs. Bixby visited the Adjutant General of Massachusetts in the fall of 1864 with the claim that she had lost five sons in the war, and this draws arguments: while some claim, at the time, she had genuine reason to believe she had lost five sons to the war-Massachusetts Adjutant General Schouler claiming she was “the best specimen of a true-hearted Union woman” , David R. Barbee is among the historians that believe she was “a liar and a schemer who sought to exploit patriotic feeling during the war for her own personal gain”. Mrs. Sarah Wheelwright, in describing her wartime dealings with Lydia Bixby, claimed that “I received a very distressed letter…saying that the police, on finding that we were helping this woman, had told her that she kept a house of ill fame and was perfectly untrustworthy and as bad as she could be.”

There is a much more grim and cynical version of the story of the Bixby letter: Lincoln delegated writing the letter to his secretary, John Hay, and the widow Bixby, being a Confederate sympathizer, destroyed the letter, a tribute to her five sons described by their townsmen as “tough”, some of them “too fond of the drink”. One son “may have served a jail sentence on some misdemeanor”

What is true? What is false? What will we never know?

The Bixby Family

The Bixby sons were the children of Oliver Cromwell and Lydia (Parker) Bixby. They first appear together in an “intent to marry” record in Mendon, Massachusetts, on September 2, 1824. The evidence available-although sparse-dispels the rumor of Mrs. Bixby being a Confederate sympathizer because she was a Richmond native and Southern belle, but rather shows that she was born to English immigrants in Rhode Island in 1801. Oliver, a sixth generation descendant of Puritans, born in 1803 in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, and named after English political leader Oliver Cromwell, was described by genealogist Willard Bixby in 1914 as a “quiet, inoffensive man”.

Oliver Bixby and Lydia Parker were married on September 26, 1826, in Hopkinton, Massachusetts. They lived, first at Mendon, then in Franklin, but primarily in Hopkinton. Oliver worked as a bootmaker and all of his sons entered the trade of crafting footwear at some point in their lives. According to vital and census records, the couple had nine children: Susan (1826), Oliver, Jr. (1828), Henry (1830), Caroline (1833), George (1836), Andrew (1839), Charles (1840), Edward (1843) and Georgianna (1847).

Tragedy struck the family in 1854, when Oliver C. Bixby, Sr., died at the age of 51 in Hopkinton of a “fit” (a 19th-century term, frequently referring to epileptic seizures). Lydia Bixby now had the difficult task faced by widowed mothers of the 19th century of finding a way to support both herself and children-in Mrs. Bixby’s case, five-who were living independently.

Described as a poor man, Oliver’s death would have undoubtedly brought added struggles to his family. According to Willard Bixby: “After his death, and for many years, his widow was a nurse, living chiefly in Boston, but sometimes in Providence”. It also appears that Lydia’s children supported her through their labor. In the seven years prior to the Civil War, Lydia appears twice on record: first, in the 1855 Massachusetts State Census, the family’s last appearance in Hopkinton, and in a boarding house in the 1861 Boston Directory, both times with two sons supporting the family through boot making.

Despite the hardships Lydia had faced, the Civil War would only bring further destruction to their family.

The Bixby Boys in the Civil War

The Bixby family, like virtually every American family, found themselves to be ordinary people swept up by extraordinary events during the Civil War. The war itself began when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in South Carolina in April 1861. Although the war raged throughout the country, the Bixby brothers primarily served in the eastern theater of the war. Their units were assigned primarily to the Army of the Potomac, which was met by a disaster in the first two years of the Civil War in their disastrous attempts to drive the Confederacy out of Virginia. After an unsuccessful Confederate attempt at invading the Union ended with the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the tide of war changed. The last two years of the war were largely spent in bloody, somewhat stagnant, attempts to drive the Confederate military out of Virginia. The war ended with a Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House in Virginia in April 1865, with a total loss of over 600,000 men on both sides. The Bixby families were no strangers to this sacrifice, as shown by the brothers’ service records.

Oliver C. Bixby was, according to the statement shown to President Lincoln, killed at the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864. Born in 1828, he was the oldest son and second child of the Bixby family. He was the only child to live in Hopkinton throughout his life, where he worked alternatively as a bootmaker and a mechanic. He was married twice, first to Catherine Wing from 1848 to 1850, and second to Watie Ranlett in 1854.

Oliver C. Bixby served in the 58th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. There is no record of him having served in the first three years of the war, and, when required to register for conscription on July 1, 1863, it was noted that his “thumb [and] forefinger on his right hand [were] gone”, which would have made him ineligible for military service. He was able to enlist as a private in February 1864, with a hefty bonus, because he opted to enlist in nearby Brookline that had not reached its quota for volunteers.

Two months later, Oliver was on his way to Virginia, where his regiment was slated to be part of General Grant’s ultimately successful, yet extremely bloody, campaign to drive the Confederate Army out of the state. The 58th first saw combat in the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5-7) and he was wounded in the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House on May 12. It is unknown the extent of his wounds, but he was able to return to his unit in time for the Petersburg Campaign. Oliver C. Bixby, Jr., was killed on July 30, 1864, in the Battle of the Crater-meaning the file shown to President Lincoln regarding Oliver was correct. His widow took their three children to New Hampshire to live with her family, and custody of Charles Carroll Bixby, his son by his first marriage, having now lost both parents, was given to Oliver’s mother, Lydia Bixby, in Boston. Oliver Bixby is believed to be buried in an anonymous grave on the battlefield or in nearby Poplar Grove National Cemetery.

Henry C. Bixby was, according to the statement shown to President Lincoln, killed in the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. Born in 1830, Henry was the second son and third child of the Bixby family. He was a bootmaker, first in Hopkinton, then in Rowley during his first marriage, then in Boston where he lived with his mother after his first wife died. His wartime civilian occupation is given as that of a sailor. He was married twice, first to Emeline Perry from 1853 to 1859 and second to Sarah Lyndes in 1871.

Henry C. Bixby served in the 20th, 32nd, and 62nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiments during the Civil War. Henry first enlisted in July 1861, in the 20th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment-dubbed the “Harvard Regiment” because of the large proportion of Harvard graduates who were officers-with his brother, Charles, the only time two Bixby brothers are known to have served together. This regiment served in Virginia, and Henry was his company’s cook for much of his service. He was discharged from a military hospital after six weeks of hospitalization on May 29, 1862, in Washington, D.C., due to rheumatism.

Henry Bixby next enlisted in August 1862, as a private in the 32nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. During Henry’s service, the regiment served in the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Battle of Antietam and the Battle of Fredericksburg, and he was promoted to corporal. Contrary to what Lincoln saw, Henry was not killed on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, but he was captured. He served time in a Confederate prison camp in Richmond, Virginia, before being paroled in March 1864. As a condition of his parole, he was not allowed to return to combat, and instead spent his time at a parolee camp in Indianapolis with men in his situation and was in military hospitals due to unspecified reasons.

Henry was discharged from the 32nd in December 1864, from a hospital in Washington, D.C., at the end of his enlistment. Henry enlisted lastly as a private in the 62nd Massachusetts Infantry in March 1865. During this service, the war ended with the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House and Henry was promoted to corporal. After his final discharge in May 1865, Henry returned to the boot making profession. Henry Bixby died in 1871 at the age of 41 of tuberculosis in Milford, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb he moved to post-war. His widow, Sarah, remarried and Henry is not known to have had any children. Henry C. Bixby is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Milford, the funeral reportedly done with military honors by local veterans.

George W. Bixby was, according to the statement shown to President Lincoln, killed in the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864. Born in 1836, George was the third son and fifth child of the Bixby family. George is regarded as the most mysterious of the Bixby brothers because of his unknown fate, the mystery only further being enhanced by additional research. The 1855 Massachusetts State Census shows him as working as a bootmaker in Hopkinton to support his mother and siblings. On July 3, 1858, he was sentenced to four years in the Rhode Island State Prison in Providence for “breaking and entering a shop”. His 1863 marriage record shows him as a bootmaker in Somerville, Massachusetts, and his 1864 enlistment record says he was a cabinet maker in New York. He was married to C. Josephine Murphy in 1863.

George W. Bixby served in the 56th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. George enlisted in March 1864, as a private. He used the alias “George Way”, supposedly to keep the enlistment secret from his wife. This unit saw combat in the Battle of the Wilderness and the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. Contrary to the statement shown to Lincoln, George was not killed at the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864, but rather was captured. A December 2, 1864, article in The Boston Liberatorstated that, “Geo. W. Bixby, of Co. B, 56th Regt., one of five brothers reported as killed in this war, was not killed, as has been supposed, before Petersburg, the 30th of July last, but was captured unhurt by the rebels. His mother has mourned his death for four months.”

His regiment kept him on their monthly unit rosters until the end of the war as a prisoner, but, when he did not return, his status was investigated. Confederate returns of prisoners show him in prison in Richmond, Virginia, on August 31, 1864, and at Salisbury Prison in North Carolina on October 9, 1864. Then, he disappeared from the record.

In March, 1865, Lieutenant Colonel Gardiner Tufts, employed by the State of Massachusetts as a Military Agent to the federal government, sent a letter to the surgeon general of Massachusetts stating that he heard from an unnamed source that George Way died at Salisbury and that $250 owed to him by his unit should be given to his mother. After the war, Corporal John Welch, another prisoner at Salisbury from Way’s regiment, stated that he “was sure that Way deserted to [the] rebel army from Salisbury”. This was a somewhat common practice, especially late in the war, as both armies had recruit shortages and men wanted any way out of the horrors of late-war overcrowded, unsanitary, generally sickening prison camps.

Unable to come to a conclusion on this, his regimental roster lists him as equally likely having deserted to join the Confederate Army to escape his current situation and as having died in Salisbury. To further complicate matters, George Way or George Bixby is not listed as a member of any Confederate military unit, or as someone who is known to have died in Salisbury. An 1874 article, although exaggerated, claimed that one of Mrs. Bixby’s sons “starved to death in a rebel prison”. In 1878, his uncle, Albert Bixby, according to Willard Bixby “became insane, imagined himself in danger, and committed suicide.”. He died without children or a will and his estate was divided up in Worcester County probate court among his nieces and nephews. A preliminary list of his heirs, dated August 1878, lists a nephew George Bixby “of Cuba”, but a secondary list of heirs from September 1879, has no mention of him.

There are also no known mentions of his wife after their 1863 marriage, nor were any pensions claimed on behalf of his service. It is possible, if he did not die in Salisbury, that, given his criminal past, his alleged attempt to get away from his marriage, and, his possible enlistment in the Confederate military, he may have used a false name and his true fate may not have been known by his family and may never be known. That may be just the way George Bixby wanted it.

Charles N. Bixby was, according to the statement shown to President Lincoln, killed in the Second Battle of Fredericksburg on May 3, 1863. Born in about 1841, Charles was the fifth son and seventh child of the Bixby family. He appears to have accompanied his widowed mother wherever she went, first appearing with her in Hopkinton, then in Boston, where he worked as a bootmaker to support her. Although he had the shortest life of the Bixby sons, he displayed a strong loyalty to his family and country, and in an 1863 pension application by Lydia Bixby, Charles’ mother, neighbors and employer all testified that Charles had been paying for his mother’s room and board in Boston since at least May 1859, and, before leaving to war he had bought Lydia six months worth of groceries. His Boston employer, Robert Smiley, stated that Charles “supported her in the same way and as fully as any man would support his family”.

Charles Bixby served in the 20th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. Charles enlisted in July 1861, as a corporal. This regiment served in the Battles of Ball’s Bluff, the Seven Day’s Battles, Antietam and Fredericksburg. Although his exact service is unknown, Charles is listed as “present” on all of his unit’s monthly rosters and was promoted to sergeant in August 1862. Charles N. Bixby was killed on May 3, 1863, in the Second Battle of Fredericksburg. Although he claimed to be married at his time of enlistment, an investigation by the Pension Office and contemporary records show no evidence of Charles having a wife or children. His mother, Lydia Bixby, was able to claim a pension of $8 a month due to her dependence on his income following his death. Charles Bixby is believed to be buried in an unknown grave on the battlefield or in Fredericksburg National Cemetery.

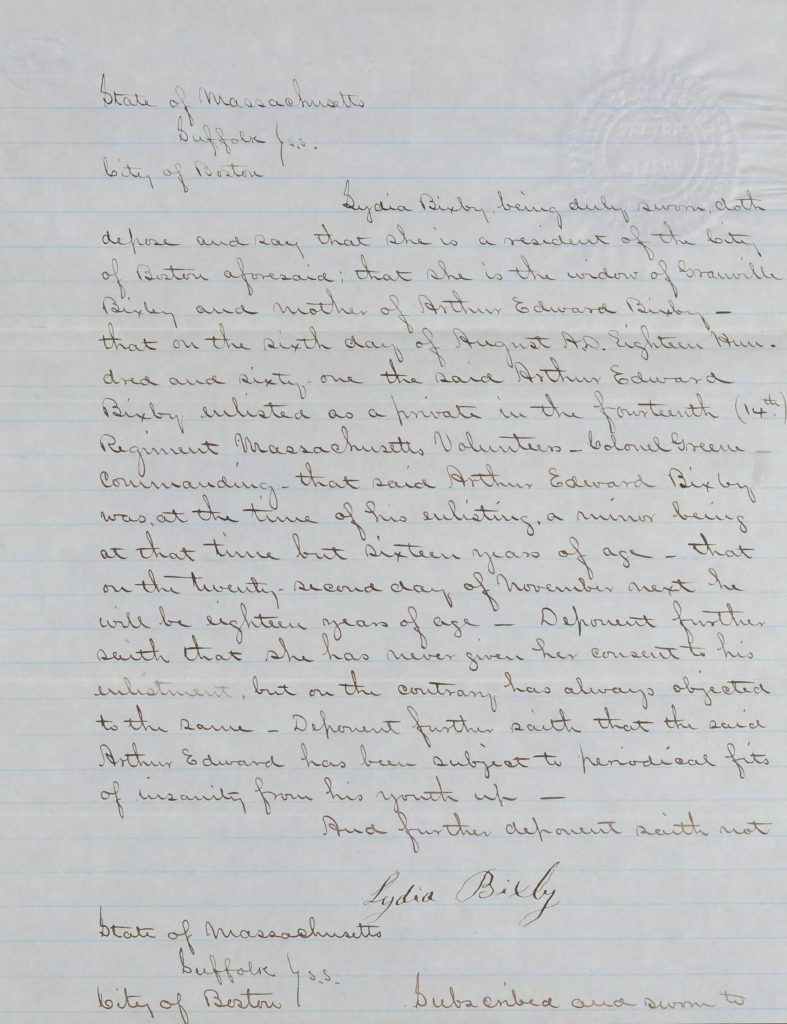

(Arthur) Edward Bixby, according to the statement shown to President Lincoln, died of wounds in Folly Island, South Carolina, in 1862. Born in 1843, Edward was the sixth son and eighth child of the Bixby family. He appears to have had a troubled adolescence, spending time in reform schools in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, but he also had the opportunity to learn the shoemaker’s trade.

Edward Bixby served in the 14th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment/1st Massachusetts Heavy Artillery Regiment. Edward enlisted in June 1861, at the age of 17, as a private. He enlisted as “Arthur E. Bixby”, and, although many researchers have theorized this was to keep it hidden from his mother, he used both names interchangeably throughout his life. An alternate theory as to his enlistment motive is that, in 1858, he was sentenced to the Providence Reform School for theft-quite possibly the same breaking and entering George went to prison for-and, if he was still there when the war broke out he may have taken advantage of a program for older students to leave the school through military enlistment. Edward’s regiment served on guard duty in and around Washington, D.C., and he is simply listed as “present” on all monthly unit rosters during his service. In October 1862, Lydia Bixby filed an affidavit stating that Edward had enlisted underage, without her permission and that he was subject to “fits of insanity” (possible genetic epileptic seizures) since his youth. A discharge was ordered, but it was discovered that he had received permission, on May 28, 1862, to leave his unit for 12 hours and never returned. Perhaps coincidentally, this is one day before his brother, Henry, was discharged from the military at a Washington hospital.

Edward has been portrayed negatively by historical researchers for his desertion. Reverend W.E. Barton, a Bixby family historian, stated in 1926 that, in regard to the popular belief Edward became a cigar roller and died in Chicago in 1909: “No Grand Army button adorned the lapel of Edward Bixby’s faded and threadbare coat. No little group of old men in blue stood around his coffin. No volleys were fired; no bugle sounded taps. This man, who as a boy of eighteen went forth as a soldier and grew homesick and deserted a year later, finished his fugitive career, and died, a man without a country.” Although this has been an accepted fact on the Bixby matter for decades, contemporary records show that the man who died in Chicago was more than likely a younger man named Edwin Bixby, a native of New York.

In turn, other period records paint a much different and more complicated story of Edward’s life. It is unknown where he was at the time of the Bixby letter and how much contact he had with his family, so it is possible Lydia Bixby may have heard false information that he had died of wounds and took it as truth. Willard Bixby has suggested that: “It is quite possible that Edward deserted from the regiment and enlisted under another name in some other, likely to see active service and at one time was in the hospital at Folly Island. The whole family were eccentric and reckless.” In December 1864, a Massachusetts native named Edward Bixby enlisted in the United States Navy for two years in Otsego, New York. The similarities end there, as this man was described as a 30-year old broker who was 2 1/2 inches taller than Lydia Bixby’s son, Edward, although this man has not been definitely linked to any other men with that name at the time. Lydia’s son, Edward, enlisted for certain in October 1866, eighteen months after the war, as “Arthur E. Bixby”, who was described as a 23-year old Boston laborer, enlisting in the Army for 3 years. He was discharged after six weeks, but he received what all researchers have said he never had a discharge from the U.S. Army.

Edward Bixby is listed as an inmate of the Suffolk County House of Corrections in Boston in the 1870 United States Census taken in June 1870. According to an Indianapolis Journal article from March 23, 1870, “Edward Bixby was before the court at Boston, Thursday, for larceny. Bixby gave his history for the past seven years. He was in the army three times, stole a passage to South America at the close of the war, was twice a policeman at Montevideo, a soldier in both Paraguay and Chile, a mechanic at Rio Janeiro and finally returned to New York.” The validity of these claims is currently unknown, but they do suggest that Edward may have been honorably discharged from the military several times and also served in the militaries of Chile and Paraguay. Although the details of his 1870 larceny case are unknown, if Edward was convicted, sentences for similar crimes suggest he would have most likely received one to three years in the county house of correction.

Despite being absent in his youth, Edward Bixby appears to have remained with his mother during her later years, contradicting the statements she was “poor and alone” at the end of her life. Edward is listed in the 1876 Boston Directory as a sailor that lived with his mother on Pleasant Street. In August 1878, Edward Bixby “of Boston” is on the preliminary list of heirs to his deceased uncle, Albert Bixby’s, estate.

Edward Bixby appeared one final time before disappearing from the record. In the final list of heirs to Albert Bixby’s estate, dated September 1879, after Lydia Bixby’s death, “Arthur E. Bixby” of Urbana, Ohio, is among those listed as entitled to an inheritance. Edward would have been thirty-six at the time, and his fate after this point is currently unknown.

The final military record of the Bixby boys is, of the five sons believed to be killed, two (Oliver and Charles) were killed, one (Henry) received three honorable discharges, one (George) has an unknown fate, and one (Edward) served multiple enlistments, possibly in multiple militaries-and is on record as having deserted from his first term of service.

Saving Private Bixby?

Although many facts of the Bixby boys have not been previously presented, there is none more so ignored than the Bixby’s fourth son and sixth child. He was born in about 1839 as “Andrew P. Bixby”, but appears as “John Bixby” (many genealogists originally speculated this was two separate sons) from 1866. He worked in the boot making trade and is shown as helping to support his recently widowed mother and siblings in the 1855 Massachusetts State Census in Hopkinton. He worked as a bootmaker and mechanic while in Boston. He was married in 1866 to Maria L. Hall.

John Bixby remains largely ignored because he was not mentioned as a son of Mrs. Bixby who was killed in action. Instead, John would have been the sixth son who occasionally mentioned as lying wounded in a hospital at the time of the letter.

Was there a Saving Private Bixby? Maybe. But probably not.

There is no record of an Andrew Bixby or John Bixby as having served from Massachusetts, or any other state, on either side during the Civil War. In fact, it is also more than likely that the sixth son mentioned as being in Readville Hospital was actually Henry Bixby, who was at first claimed to have been killed at Gettysburg, but was actually captured, paroled and was at Readville for a few months prior to his discharge in December 1864. While it is possible that John may have served under an assumed name, the darker possibility persists: since the rumor of Mrs. Bixby’s sixth son was never put to rest, is it possible she lied, or was complicit, about the exaggeration of her situation?

Did Mrs. Bixby Lie?

The answer is probably.

A Boston Daily Globe article, dated April 4, 1874, claiming to be from a “volunteer” about a recent visitor charitable organization, said the following:

“Mrs. Lydia B. Bixby, widow of Oliver C. Bixby, aged seventy-three, now residing at No. 54 Pleasant street, lost six sons in the army of the republic; four were killed in action, one starved to death in a rebel prison, and one died at home from consumption contracted during services. Mrs. Bixby receives a pension of $8 per month and State aid amounting to $4 per month, and has no other resource, being now crippled with rheumatism from living in a cellar. She has until recently earned a trifle by taking care of sick children, and by the use of her needle, and has been aided from time to time by charity. She is an American, and lived many years in Hopkinton, this State; and during the life of Governor Andrew and General Schouler was cared for and promised made of an extra pension from the State, in consideration of her great sacrifices.

The “volunteer” asks: “If Boston, if Massachusetts, will allow such destitution to exist within her limits without immediate and generous relief.”

This article serves two purposes to historians. First of all, it does show that the widow Bixby continued to claim the loss of all her sons in the Civil War, even long after the end of the war, this time raising the number of sons lost to all six.

The argument that Mrs. Bixby may have truly believed at the time she received the letter from President Lincoln that all of her sons had died in the war could be made irrelevant through this. This article, nine years after the war-this time with all six of her sons dying because of the war-shows that she may have realized the opportunity she had to receive charitable giving through exaggeration. The other possible reason is that the family may have operated with little awareness for each other. The 1870 Indianapolis Journal article about Edward’s larceny trial ended with: “He is the sixth and only surviving son of Mrs. Bixby to whom President Lincoln wrote, in 1864, a feeling letter of condolence for the almost unparalleled loss she sustained by the death of five sons sent to the war”. Could all of the surviving sons, at least for a time and maybe if they were not in contact with their mother, truly believed themselves to be the sole survivor?

Secondly, the Boston Daily Globe article also displays the extreme, perhaps exaggerated, poverty that Mrs. Bixby lived in during her later years. According to historian Kendall Banning, “she died, poor and alone, in the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston on October 27, 1878”. Charles Carroll Bixby, her grandson through Oliver, Jr., that she had custody of, died in 1870, at age 21, and they are buried together in forgotten, unmarked graves in Mt. Hope Cemetery in Mattapan, Massachusetts.

Did she die “the best specimen of a true-hearted Union woman” or “as bad as she could be”?

Why, based on the evidence and the complexities of man, could she not have been both?

Josh Nieters is a paralegal student at Minnesota State University-Moorhead. He has had historical research articles previously published in Utah Stories magazine, the Sun Journal (Lewiston, Me.) and the Times Observer (Warren, Pa.). In his free time, he enjoys running, biking and spending time with his friends and family.