The Charm Offensive: Chapter 2

(This is the continuation of the serial novel: The Charm Offensive. Please read the previous chapter.)

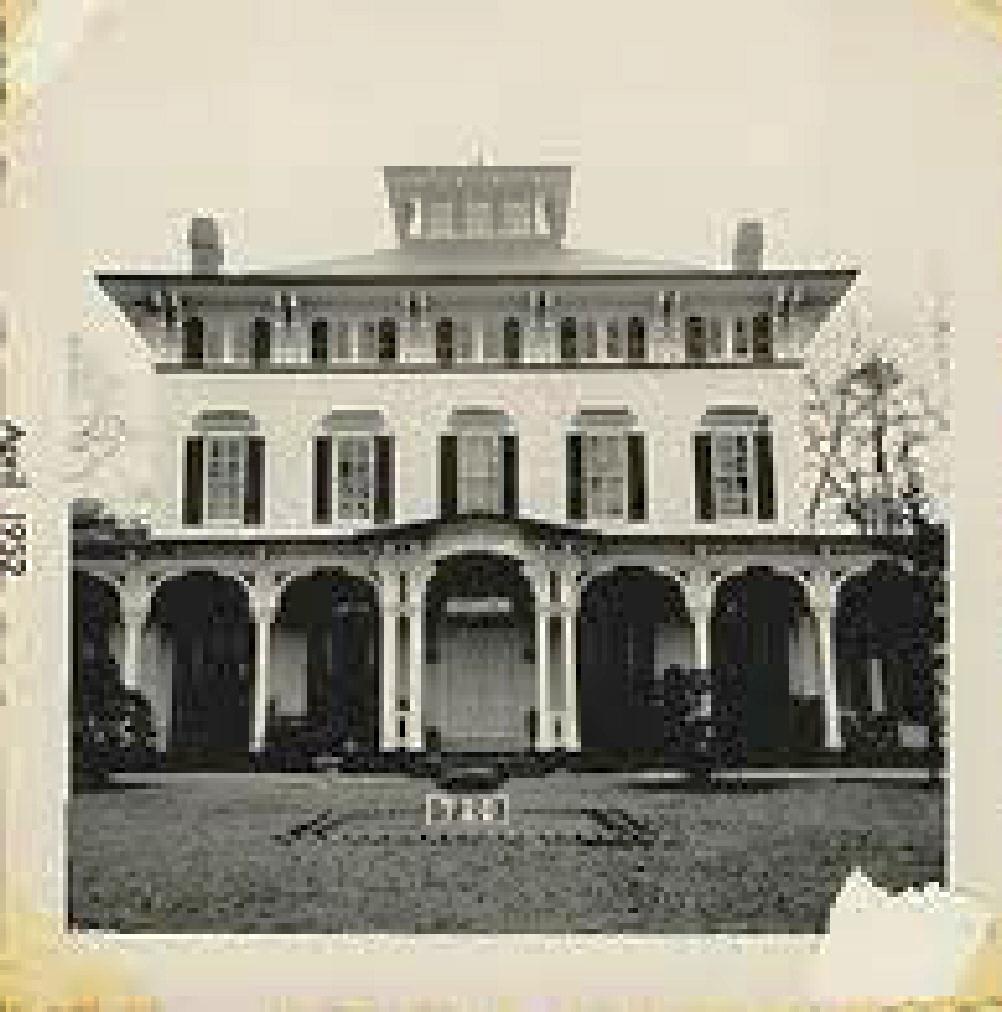

The Homecoming (Twelve Years Later)

When I arrived I was a sight. The ride from the Freemont Academy for Wayward Negro Girls was a rough one. Of course, this was not the institution’s proper name, but considering my purpose for being lodged there for the previous three years, it might as well have been.

We drove straight through from New Brunswick to Baltimore. Setting off before dawn. Not even a mumbled “safe travels,” or a wish good luck from the apple sour lot of ‘em. The only display of human warmth was demonstrated by the Academy headmistress, Miss Hattie Rangale, who though bundled against the cold in only a gingham dressing gown and double crocheted shawl, was red-faced splotchy and misty with perspiration.

“Well Mayella, Dear,” she said, stamping one muled foot and then the next against the cold, “Please do what you can to remember all Freemont attempted to teach you—we don’t give up often, but only God knows ones truest path. It’s neither our place, nor duty to salvage souls who do not want to be saved.”

“I always do what I can, Miss Rangale,” I said, rubbing sleep from my eyes. “Yes, ma’am, the Academy taught me the time spent puttin’ y’all foot in another’s back, could be spent lendin ‘em a hand.” I said this, and then quickly ducked my head back inside the car window, but not before yawning in a bored and all too exaggerated manner. I did this so she wouldn’t mistake my words as a show of genuine contrition, one last ditch effort to soften her heart in order to allow me to stay.

As the car made its way down the Academy’s circular drive, I did not do what I did the first time I was expelled from Freemont – stick my fingers in my ears and lick my tongue out. Nor did I do as I did the second time I was expelled from the Academy. The time Delores, my mother, got Miss Reynolds to ask her brother, Mr. Kenny, now an even richer owner of two auto mechanic shops, to allow one of his boys to drive up and bring me home – I did not drop my Tuesday bloomers and shake my hiney out the twin’s truck window. An act which caused the twin, I can’t say which, either Malcolm or Martin, to begin beeping the horn in a frenzy, each beep matching my gyrations, shouting as the pickup spieled off, “That’s the way Mayella, girl, you show ‘em how Hollis Street do!”

My acclaim for what Delores called “that deplorable antic” would follow me the rest of my life, taking on a life of its own most certainly among the brownstone’s old timers. Miss Carol’s nephew, who was supposedly only visiting for the summer, began telling anyone who’d stand still long enough to listen, stories with me as their central character. Most were of little note. ‘I saw her at the corner store buying cigarettes; I heard her swearing like her mama ain’t her mama’–really, nothing of true consequence. But one of his lies questioned who raised me up, casting undeserved aspersions on my mama, and it was this more than him tellin’ schoolyard tales, that made me cry. Torrential tears, so many that one of the twins, perhaps Martin, perhaps Malcolm felt the need to talk it out with Miss Carol’s nephew, one nineteen year old to another. After that it was settled. Miss Carol’s relation, who she would later disown in an apology to me, had been mistaken. It wasn’t me who “gave him one fine ride” in the basement laundry room. I wasn’t the gal who “gave it her best” in the back row at the Royale. This was clear. Besides, it couldn’t have possibly been me, as perhaps Martin, perhaps Malcolm explained to him: “‘Cause Mayella’s like a baby sis to us, and she don’t know nothin’ bout things like that—she’s a good girl. And even if she did—and she didn’t–nobody better be talkin’ bout it. ‘Cause, if they did then we’d have to do somethin’ bout such a person tellin’ such lies on baby sis.”

After this, every time he saw me, he’d walk real fast in the opposite direction, like he hadn’t gotten his shots and I had the pox. Then one day, like so many things in life, Miss Carol’s nephew up and disappeared.

Truth told, the only person I actually showed ‘how we do it on Hollis’ was Mr. Tidwell, the oldest gardener in the State of New Jersey, having been in service to the Academy grounds since the beginning of time, practically since the twenty-two plus acres and accompanying structures were endowed to the school. But he hadn’t appeared to mind.

No, this time, I sat back pulling the blanket that was folded on the seat over me. I settled in for the two hour ride back to Baltimore, which was good, considering, this early morning there was to be no stopping. Not even a brief pit stop for dignified human relief. There was a schedule to keep.

“Then, can we please stop and get somethin’ to eat?” I understood I had just asked to stop to pee, but I figured if I could get him to stop for food, then by default I’d get my bathroom break.

“…foods at the house,” the driver mumbled, and then–and this seemed more pressing than anything else that wasn’t allowed, “Now, stop with your yammerin’. It’s way too early for all that. Just sit back and be good…go on and get you some sleep. You’ll be home soon enough,” he said, checking the rearview mirror one last time, then applying several back and forth jerks to the radio’s dial, finally tuning in and settle on a gospel station spinning soft, yet mournful songs originating somewhere out of Richmond.

The driver, a man named Benny Toussaint, was spit shine. And like my granddaddy had been, this day, he leaked old-time Negro dignity. He was also someone I recognized right off as a Hollis Street regular, a man who on Sundays the women of 1900 Hollis took extreme measures to avoid. So much so, if some were cooking proper Sunday suppers, and Benny was known to be lurking, then rugs throughout the building were shoved against door cracks to keep smells from wafting out into the hallway. This same man, a person I had seen devour all manner of pig–rooter to the tooter—like a ravenous dog at our kitchen table, was the one Delores had chosen to drag me home. And now here I was, practically starving, forced to listen in the dark for the crinkle of wax paper and for the noisy smacks he made chewing readymade sandwiches, sandwiches he had not even offered to share.

For my arrival, Delores wanted me to be wearing my Freemont get up. “And, don’t forget to wear your uniform home.” I knew she had requested this as part of my punishment, punishment for making her endure so much back and forth with the school, the begging, the wheedling, the promises, before finally coming to terms with The Academy’s last words on the matter: She’s expelled; this time for good.

Though the uniform’s blue and red striped skirt chafed, I did not see this as such a bad thing. In fact, it would keep me awake which would greatly aid me in going directly asleep when I arrived home and in avoiding having to endure “the lecture” from Delores straightaway.

All the same, before I was able to make myself even half way comfortable doors are slammed, first the driver’s and then the trunk. “Hey, wake up. We’re here,” Benny said, straightening his own uniform. In the time it would’ve taken a gnat to pee, I was back home again, and had wrapped not even one finger around the knocker when the door was snatched open.

“Com’on here, chil,” Delores said, not sounding like herself, but like someone else’s good and dutiful mammy. That same mammy mother Freemont Academy mean girls would point out and made fun of on All Parents’ Day. Though tired, I was still surly from having to endure my rough ride and so, I poked my lips out and shook my head no.

Little Leni, who had been hiding behind Delores, lurched forward to surprise me. Entangling our limps with the sweater I had tied around my waist and my satchel looped over my shoulders. Way up and over us, past the inlayed gold and teak foyer, I saw him standing on high, atop the library stairs. I rubbed Leni’s back and smoothed her hair, which I knew from the smell of Dixie Peach pomade, had just that day been combed. This made her hug me more urgently, tighter around my waist. If we hadn’t been bundled as we were, I would have hoisted her up and raced back through those wrought iron gates, hightailing back North, or South, or West. Anywhere, really that got me out of his sight. If not for Leni, Delores would have been left standing in my dust, with only Mr. Herbert’s disapproving grimace to confirm I had arrived.

With New Benny carrying my suitcases and Leni as my guide, I allowed myself to be led up the main hall stairs, not the stairs I would come to take each day for the next two years, the rear kitchen stairs, but the long and winding spiral staircase which followed a trail of water colored cherubs to the top. What turned out to be the longest possible way to my room on the third floor.

“Go on and get yourself settled, breakfast’s on. I know you’re hungry after that long ride,” she laughed a little, though she sounded nervous. “Leni, now you show her, make good use of yourself, hear?” Delores said.

“I will,” Leni answered, happy to be the boss of someone other than her dolls.

The room was smaller than the room I had to share with three other girls at Fremont. Smaller, still than the room I had to myself when we lived on Hollis. I walked over and looked out the window, staring down onto the garden, estimating a near fifty foot drop. I took out my diary from my suitcase and sat down at the room’s only furniture other than the bed–a child’s small desk and chair. I was not able to get even a word down before I heard the hiss, and felt wet heat on my neck.

“What?” I asked, finally looking back at Leni, who was breathing hard and staring at me.

“Well, what you wanna do now?”

I looked her up and down, then stood and began taking neatly packed clothes from the suitcase, dumping everything onto the bed.

“If you got nothin’ better to do than breathe, then do like she said, ‘be of good use’ and put my clothes away.”

Her face scrunched up, then as if she had suddenly grown a new, better brain, she laughed and said, “You do it,” and quickly skipped, heel toe, heel toe, out the room.

This was good. I was tired and wanted to get ready for a much needed nap, though I had slept most of the way when not awakened by Benny’s chewing and spontaneous gospel outbursts: “Yes, Lord!, Oh, Lord!, My Lord!” He had sounded somber, yet threatening, which I thought was noteworthy, and was about to scribble this in my diary, when Delores yelled again, “Com’on, now, food’s ready!”

I waited to reply. I needed to get my thoughts down before they got all mixed up and turned around once Delores got at me. “Delores, can a person sleep past seven around here? Please, it’s only 6:15,” I hollered back, starting at the sight of Leni, back again, now tugging at droopy lace-edged socks.

“Yeah, but you don’t look sleepy?” she said.

“Shut your little face,” I said, rolling my eyes, making my lashes flutter even as a second voice, his voice, bellowed from below, “No, you cannot! And don’t address your mother as Delores. She’s your mother. Period.”

“Shhh,” I said, putting my finger to Leni’s lips to stop her laughter.

Then, “Cook’s made a big tub of porridge, sausages too, for you girls. So, com’on down before she makes me eat it all,” he said. Then a soft little giggle, a woman’s. I can’t be sure, but I think it might have been Delores. Though I had never known her to giggle, or, for that matter, laugh.

“Thanks, but I’m not hungry—Sir.” I waited, listening, raking fingers through my hair, ready to slip all of it into a knot atop my head and wrap my head in my bed scarf to better aid the additional sleep I was about to dive into, when an odd silence came over the house–the clanking of pots and pans, grown folks’ back and forth, even the distant rustling of trees, all stopped. It was quiet, like what Dedri’s Aunt Faith, a mid-wife, explained came over her and the other ladies holding the woman down when they saw the baby had three arms.

Then, not especially soft or loud, he said, “Ella, be quick now. We’re scheduled people here at Burlington House. I thought your mother made this clear–matter of fact, I’m sure she did.”

When I did emerge, I took the stairs as slow as humanly possible. Slower than the infirmed, old money grandparents of my school mates, slower than their senile great-grandparents who asked to take the Academy grounds tour, but just as quickly forgot why they had wanted to. Slow, but still moving forward, I hit the next step to last, and listened to their two voices intertwined, sounding tighter than the links of the rope chain my daddy got me on my twelfth birthday:

“She flunks out of a middle of the road colored prep school, Mr. Herbert. And now, even the public schools don’t want her.”

“History,” he said.

“Sir?” Delores, asked.

“Cain and all his brethren—Sorry, go on, Delores, please.”

“The headmistress called her corrosive, Mr. Herbert–which was clearly not right…but really, corrosive…”

Silence.

“But then she has to go on and correct her. Can’t leave it be…goin’ on to tell her, ‘Miss Rangale, do you mean coercive, because that seems, more, well…more, me.’”

Then the roar, laughter–His. “Perhaps, they’re both right, Delores,” he said, still laughing.

“Now, don’t go and get me wrong, Sir. Mayella’s got a lot of lip, but she’s whip smart.” I knew she said this to make him understand that it wasn’t just dumb folks who do dumb things. Smart folks do them too–just take a look at her child.

“Well, Delores, let’s see how this goes. Ella’s got an opportunity here that most girls don’t ever get – one that will not be extended again.”

“Sir, I know. Maye—Ella’s head’s gotten hard with her daddy’s passin’, but she’s on the right track now.”

“James was a good man,” he said, “Overly optimistic, at least when it came to his limitations, still….”

“Well…I suppose,” she said. “He had a big heart. That’s true enough.”

I sat down on the stairs. She was right. When daddy died, things changed in me. He was the one who saw me for my truest self. He made it easy for me to be good. But now with this latest expulsion, Delores had had to–as daddy would have seen it–let down her hair and hike up her skirt, and ask Mr. Herbert to intervene on my behalf. I remember him saying when she first said she wanted to leave the school system and go work for Mr. Herbert, “A woman oughtn’t to put herself in a position where she has to do things not in her nature.” I didn’t know then but I know now what he was saying. Delores could no longer afford to be grandly formal but deferential to her employer of the last five years. Now, because of me, she not only had to do a good job, she also had to like and be this man’s friend.

“Well, I certainly hope so,” he said, “Short of buying a school for her to attend there aren’t too many other options. You certainly don’t want her running wild at the Hollis property.”

“No, I don’t want that.”

“I didn’t think so.”

“And, I thank you, Sir—We thank you.”

“So, when’s the tutor to start?”

“Next week, Monday. She said she could take on both girls.”

“Good. That way both will be close at hand,” he said. “No need Leontyne picking up Ella’s ways.”

“No, Sir,” she answered.

I was just about to rise up and haul butt, when Leni jumped onto my back, all yip and yea at the thought of food.

“Whatchu forget?” she said, plaits swinging over my shoulders.

“Hush, you booger.”

“Hush your boogerself!”

“Ella, that you?” He asked.

“It’s her.” Leni squealed, assuring herself an extra sausage with her porridge.

“Ella?” said Delores.

Ella? “Yep. I’m comin’.”

“Yes,” he corrected, his voice booming out past so much columned hallway, out past the portrait of the very first Mr. Herbert, his great-granddaddy, the sight of which, turning my insides the same way drinking pot liquor on an empty stomach does.

By the time I entered the kitchen, Delores had taken over the scooping of porridge from “Cook,” who I had yet to see, hear or experience in the slightest. Leni had just begun her sausage gnawing, every blunt tooth having at it. At the end of a table large enough to host one of Miss Reynolds’ Bid Whist tournaments, sat Mr. Herbert. With several empty seats available, I headed for the seat nearest Leni. Not looking up from his papers, he jerked the chair next to his own away from the table, disturbing the bifocals balanced on the bulb of his nose only the tiniest bit. I took the seat beside Leni.

“So, what plans do you have today, young lady?”

“Well, I thought once the girls are finished eatin’ breakfast, I’d get them workin’ with me on a couple of–” Then Delores’ voice suddenly got quaky, and she was silent. I looked up, having only just broken the surface of my bowl of glop and caught eyes the color of dead crabgrass as they lowered again to survey barely touched breakfast: four triangles of toast, along with an egg, propped up and cozy in its own cup, except its head had been chopped off. I watched, stomach getting all churny as he drank his coffee, sip, slurp, sip, slurp, and rooted his spoon inside the egg’s topless head.

“Well, are you capable of providing an answer, or are you hard of hearing, too?”

“Me, Sir?—No, Sir.”

“Young lady, don’t try me.”

I hadn’t begun to form an answer before my mother was there at my side, and my face was on fire.

“Mr. Herbert, I apologize, she’s just, this is… it’s all new to her.”

“I hope that’s all it is, Delores.”

“Oh, Sir, it is…”

I was dazed, hard pressed to comprehend ceiling from floor, blood from my eye from tears on my cheeks. Months later in my explorations of the mansion’s library, I would understand from Hershel’s Study of Negroid Body and Psyche, 7th edition that I was in shock. Leni probably was too, but not at all in the same way. Her tears did not run down her face, but held steady on the rims of her eyes. And while her lips were still clamped around a piece of sausage, she no longer appeared able to remember how to chew.

Delores had lost her mind, striking me as if she wanted me to hurt. Something she would have never thought to do when daddy was alive, not unless she also planned on losing her life. My daddy would have taken out his blade, the one with the pearl handle, and cut her throat with such a light hand and so fast, she might even think she had time left in this world to say ‘sorry,’ but she wouldn’t have. She’d be dead

He looked up, and then back down at his newspaper. I looked over at my mother, who now busied herself with Cook’s duties: re-rinsing and stacking dishes that even a blind man peering through partially shuttered windows could see were pristine.

I continued to watch Delores, finally getting her to notice me, but as I stared deep into her brown eyes, I no longer saw myself in them, and I knew things had changed.

—————————

© 2012 Willett Thomas

Willett Thomas is the president of Write of Passage, Inc. She earned her MA in writing from Johns Hopkins. She has received artist fellowships from Blue Mountain Center and the Millay Colony. She was selected as a Mid-Atlantic Arts Foundation fellow for the District of Columbia, and is the recipient of the 2008 Maureen Egen Writers Exchange award for fiction.