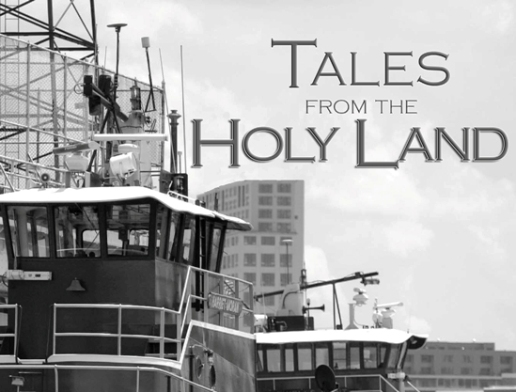

Tales from the Holy Land

Baltimore Post-Examiner is proud to present an excerpt from Baltimore-based author Rafael Alvarez’s latest book – Tales from the Holy Land. This is the third collection of short fiction from Alvarez.

The stories take place along the narrow streets and alleys of Alvarez’s heartbreaking hometown, charting secret histories of the last 100 years through the difficult and hopeful lives of tugboat men, junk collectors, beautiful women, short order cooks and an artist who captures it all in house paint on the sides of abandoned buildings. Please purchase the book at Amazon.

AN ALLEY MOST NARROW

The waterman’s widow sat on a milk crate sizing crabs by hand, bushel baskets by her brown and purple knees as she talked about a Baltimore childhood during the Second World War, more money to be made at Sparrows Point than working the waters of Crisfield.

“Back around the other way now,” she said, waiting for the truck that took the day’s catch to the city that left its mark on her decades earlier.

It was her mother, she said, who had the good wartime job as a tin flopper at Bethlehem Steel; her mother who stitched new outfits for the same baby doll every year; her mother who only asked that her husband get a tree for the rowhouse they rented where Decker Avenue hit Boston Street, the block torn down years later for a highway that was never built.

“Mom did it all,” said the woman. “You couldn’t depend on my father for anything.”

Only a drunk would wander from one end of town to the other for a Christmas tree when you could buy a hundred of them right around the corner.

When the whistle blew at the Baylis Street broom factory, the boss called everyone to the loading dock for the traditional turkey, a fifth of Maryland Rye, thanks for a job well done and have yourself a very merry.

Walter Waddell walked away with the $16 weekly pay he got for painting broom handles, the frozen bird under his left arm and his fist tight around the bottle.

“Who’s bringing home the bacon tonight?” laughed Walter as he passed Whitey Stefan’s saloon. “The kid is gonna call me Sanny Claus.”

Beyond the neon and fake snow, Walter spied an old friend and ducked in for a quick one, two at the most. He took a stool by the door, set the bird and his bottle on the bar and ordered beer for himself and Willie Jones, a neighborhood saloon singer with a soft spot for Jolson.

“By the time the old lady gets off the streetcar, I’ll have the tree up, turkey coming out of the oven and the girl cleaned up for dinner,” said Walter as a toy train emerged from a cardboard tunnel, blew its whistle and snaked through rows of sparkling bottles.

“Then you better get moving,” said Willie, finishing his beer. “I’m headed over Silks to do a couple numbers.”

“Then you better get moving,” said Willie, finishing his beer. “I’m headed over Silks to do a couple numbers.”

“One more and I’ll walk you down,” said Walter, motioning for the barmaid to set them up. “Aggie Silk makes a good pea soup.”

On the other side of the world, Allied troops trudged across the Marshall Islands. Across the harbor in Fairfield, Bethlehem Steel launched its 300th Liberty Ship of the year, the Arunah S. Abell.

Walter quaffed a quick one and followed Willie outside, uncorking the rye on the sidewalk to share a belt with his caroling friend and leaning against a stack of tires in front of Tolan’s garage to watch the red-headed Welshman amble down the street singing, “God rest ye merry gentlemen . . .”

By the time the sun was down, the temperature had dropped to 15 degrees and Walter was headed over Edison Highway on a streetcar, offering his bottle to anyone who crossed his path.

Back at Stefan’s, no one could remember who’d left a turkey at the end of the bar so Whitey’s wife threw it in the oven and made sandwiches for everyone who didn’t have anything better to do on Christmas Eve than sit in a gin mill.

One went to a nine-year-old girl who popped in to ask, after scanning the crowd, if Walter Waddell had been there. No one was sure, but hey kid, take a bag of chips and some sodie pop to go with that sandwich.

By the time the girl lay in bed hoping there’d be a new dress for the doll sitting where the tree was supposed to be – wondering how a sugar plum was different from a regular plum to keep from wondering whether her father would show up before Santa did – Walter was arguing with an elderly black man selling trees outside the 29th street tinderbox known as Oriole Park.

“Three dollars,” said the man, switching off a string of lights.

“It’s after midnight,” said Walter, knowing the time but unable to account for its passage between the last drop of rye and a boilermaker a moment ago at a tavern across the street. “You ain’t gonna sell it now.”

“Ain’t gonna give it away neither,” said the man, locking the gate. “Why’d you wait so long?”

“You know,” said Walter, fishing out his last dollar and pushing it through chicken wire with frozen fingers. “It sneaks up on you.”

The man grabbed the closest tree and with a strength that made Walter glad he hadn’t pushed his luck, heaved it over the fence.

“Now go on home, mister.”

A sharp wind blew off the harbor, across empty streets and through Walter’s pants in the hours it took him to walk from 29th and Greenmount to 1214 South Decker Avenue with a six-foot Scotch pine over his shoulder.

Sweat froze across his brow and pine needles stabbed his back and neck, sobering Walter up enough to realize that he’d done it again.

“She’s gonna mop the floor with me,” he mumbled, hoping to sneak in the back door without waking anyone.

Reaching the long, narrow “airy-way” that divided his house from the one next to it, Walter made for the nickel gray light of Christmas morning.

Unlatching the gate, he dropped the tree and slumped against the cinderblock wall, hoping, just before passing out, that his wife hadn’t locked the storm door.

She stood in the window above his head, having walked the floors all night after borrowing an artificial tree from a neighbor, their daughter gripping the sill with her nose against the cold glass.

“Okay,” she said, pulling her housecoat around her. “Go down and let him in.”

All rights reserved, 2013, Macon Street Books

Rafael Alvarez has lived in Baltimore his entire life except for a brief and cautionary exile in Hollywood. A former City Desk rewrite man for the Baltimore Sun, Alvarez has published books of fiction, memoir and very provincial history. Best known works include “The Fountain of Highlandtown” and the on-going “Orlo & Leini” stories, each detailing life in Crabtown, USA. Alvarez also worked as a reporter for the Baltimore Sun prior to starting a career in television. He has worked as a writer and story editor on the Home Box Office drama series The Wire and a writer and producer on the crime dramas Life and The Black Donnellys. He has written several books including a guide to The Wire, a non-fiction guide to the archdiocese in Baltimore, a short-fiction anthology and two collections of his journalism. He can be reached via [email protected] or [email protected].