Military, civilian scholars discuss lasting impression of WWI

Paul Sunderland’s Glass Bridge & Poppy Field at the National WWI Museum and Memorial. (Courtesy)

On Thursday, March 29, the National WWI Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri marked the final year of their centennial commemoration of WWI with a panel discussion on the lasting impression of the Great War.

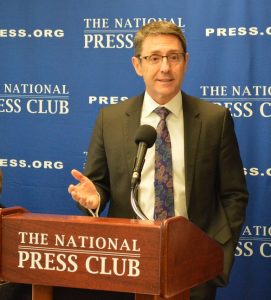

The informative roundtable took place at the National Press Club in Washington, DC.

In setting the stage for the discussion, a museum release noted that World War I is often referred to by historians as the defining event of the 20th century. The conflict resulted in the deaths of more than 16 million soldiers and civilians, and left in its wake a path of political destruction and dramatic social upheaval that can still be seen and felt one hundred years later.

John Hughes of Bloomberg News served as the event moderator. The panelists included:

- Dr. Matthew Naylor, President and CEO of the National World War I Museum and Memorial

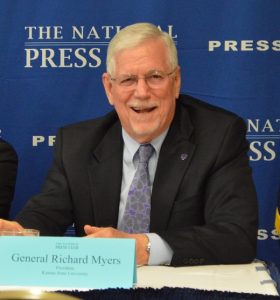

- General Richard Myers, President of Kansas State University and a retired four-star general in the United States Air Force who served as the 15th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

- Dr. Margaret MacMillan, best-selling author and Professor of History at the University of Toronto

- Dr. Michael Neiberg, best-selling author and Chair of War Studies in the Department of National Security and Strategy at the United States Army War College

Hughes opened the discussion by asking, “How is World War I different from the wars which followed, and how do we as Americans think of it today?”

“The memorials that were built in the 1920s and early 30s contain language like ‘The Great War for Civilization’ and ‘The Great War for Freedom’,” said Neiberg. “But there was a kind of feeling that I think actually begins in the early 1920s, that the peace isn’t going to be worthy of the sacrifice of the people who went through it. So, there is a sense in the American memory that the war was worth fighting, but the peace that came out of it didn’t justify that sacrifice. I don’t think that has ever gone away. World War I suffers in contrast to the Second World War, in which Americans believe the peace did achieve what it wanted to achieve.”

“I would only add,” said General Myers, “that I think it is generational, in how people perceive it. Older generations probably have a memory of a relative serving, because so many did serve. But as you get to younger generations, that was so long ago, that it’s ancient history to them. That’s one of the beauties of that museum there in Kansas City. It brings that history alive, so people can learn the lessons of World War I.

“People need to know how you get into these kinds of conflicts, so when they select politicians, they have a backdrop of how things can go wrong. I think that’s why it’s important that we’re here discussing the centennial. There is a lot to learn from World War I,” said Myers.

Naylor addressed the question of what makes the National WWI Museum a unique storyteller of The Great War?

“What we do there, I think, is unpack the story in a way that makes it very accessible.

“The museum began collecting in 1920. With about 300,000 artifacts, it is the second oldest collecting institution in the world of World War I archives. We collect encyclopedically from all the belligerents and then seek to tell the comprehensive story.

“We currently have the monumental work of John Singer Sargent – “Gassed” – from the Imperial War Museums in London. Here, we have a conversation about the detection and protection of chemical weapons from World War I and up to recent times. What is striking about that exhibition is that normally, the art is exhibited with other art. We believe this is the only time that this painting has been exhibited with objects. So to see the actual gas masks, to see the protective clothing that was used by the soldiers is very moving.”

“The United States is not mentioned until halfway through the main gallery of exhibitions. It’s not a U.S.-centric museum, although I think it does a fantastic job in the telling of the US story as well,” said Nayor.

The panel was also asked about commemorations in other countries?

“I think how people remember the war depends on the country they are in,” said MacMillan.

“What the British have done is probably the fullest of all commemorations. It’s been quite clever, and they have tried to link it to the present at so many different levels. They’ve encouraged contemporary projects, like the poppies at the Tower of London. Every school has sent at least one child to the north of France.

“The German commemoration has been very low key. But what has been interesting is an attempt to make it cross boundaries, because it was a global war and countries involved in it all suffered effects in some way or another. The French and the Germans have done a lot of memorialization together. There was actually a very moving ceremony on the anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War, where French, German and British choirs sang together at a commemorative service on the western front.”

“This is more of an academic than a popular issue,” observed Neiberg, “but I attended conferences in Portugal, Spain and the Netherlands, looking at the impact of the First World War on countries that were either neutral or had a relatively small role. The point which needs to be emphasized is that, while a country like Spain tried to stay out of it, it was still an enormously important event – leading to things which are easily traceable going back to a war in which Spain remained neutral.

“This is also true of places like India, Africa and the Middle East, that sent solders who were deeply impacted by the war. The war was a global phenomena that had a massive impact on places very far away from France and Germany,” said Neiberg.

Picking up on Neiberg’s point about the global impact of the war, MacMillan briefly added, “I think what is very touching is that, when you go to somewhere like Menin Gate, you will see names in Chinese characters. You will see Indian names and Australian names.

“A million Indian soldiers fought on the Eastern and Western fronts, so it was a massive movement of population. And what that had was an impact of the empires, as many saw the empires really weren’t superior. So you get a tremendous boost in nationalism after the First World War,” said MacMillan.

Following up on an earlier comment by Gen. Myers — who somewhat lamented the absence of a NATO-styled alliance in the Pacific today — the Post-Examiner asked the panel if the treaties which existed before the beginning of World War I made the conflict inevitable, and if there are any lessons we may glean from such alliances today?

“The thing about international treaties is always the enforcement,” said MacMillan, “and there is no body you can appeal to, to say this person did not live up to their treaty. Italy had a mutual defensive alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, yet it didn’t enter the war on their side. So I think the treaties are sometimes blamed too much. They weren’t as tight as they are often said to be.

“Britain had no defensive alliances but it had understandings. I think if a nation doesn’t want to live up the terms of a treaty – particularly in matters of war and peace – it can find an excuse. I think what was much more important in the outbreak of the First World War was the issue of national pride. ‘If we back down, we will appear weak.’ Credibility is what we call it now, but it was honor back in those days,” said MacMillan.

Neiberg added, “Treaties and alliances and structures like this work when the interests are all moving in the same direction. It’s much more complicated than people sometimes want. The line that I sometimes use is there’s a five-minute way to explain the origins of the First World War and there’s a one-semester way. There’s not much in-between that holds water. So I think the alliances are one way to put the five-minute way in, but it doesn’t actually work.

“Forty-eight hours after the assassination of the archduke, the newspapers had nothing,” noted Neiberg. “Nobody cared! It’s the way Austria reacted to this fairly minor thing that had everybody freaked out. It’s not so much the incident, but the way individuals and states reacted to them. That’s the lesson I try to give to my students. It might not be something big between two or more states that causes a war.

Neiberg continued, “Forty-eight hours after the armies started to clash, they all knew what they had gotten themselves into, but it was too late to fix it. The question of ‘How do we get ourselves out of this?’ took four years and eight million dead.”

“The danger in the Balkans (of 1914),” said MacMillan, “which is not unlike what we have now in the South China Sea, was a very small area with local rivalries and big powers interested, and that’s dangerous. It’s like parts of the Middle East as well.

“I don’t believe that history repeats itself, but we are seeing things today that are very worrying.

“People in Europe are saying ‘War is coming’ and once you begin to say that, it makes war all that more likely. You expect that people on the other side are saying it, too.

“It’s not the same as 1914, but I think there is enough there to make us be careful and warn us a bit.”

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”