Release of Adnan Syed focuses attention on Maryland wrongful prosecutions

By Abby Zimmardi and Shannon Clark

BALTIMORE – Attorney Erica Suter recalled the disbelief in the voice of her high-profile client, Adnan Syed, the subject of the viral podcast “Serial,” when the judge told him he was being released from prison after 23 years for a murder Syed says he did not commit.

“At the trial table, he turned to me and said, ‘I can’t believe it’s real,’” Suter said.

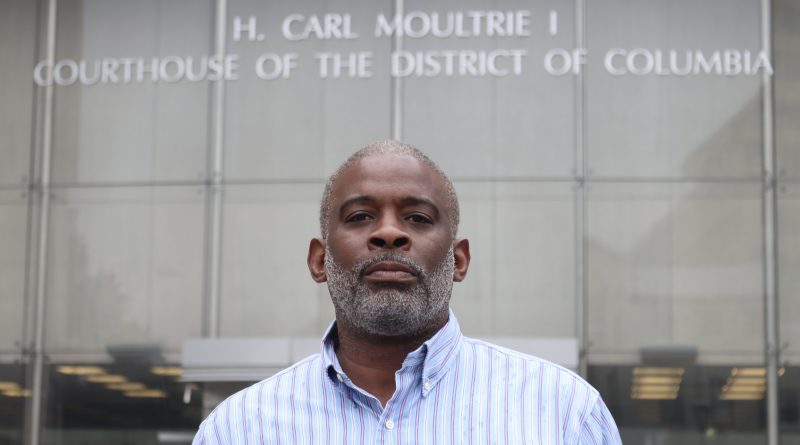

Troy Burner, 50, remembers that feeling. Burner, who also lives in Maryland, spent 25 years in prison for a crime he did not commit before a judge ruled in 2018 that like Syed, prosecutors had failed to give him a fair trial.

Syed and Burner are just two of thousands of cases of wrongful prosecution, according to records and attorneys at the Innocence Project.

At least 3,000 exonerated individuals in the U.S. have spent a combined 25,000 years of their lives behind bars due to wrongful prosecution as of March 2022, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, a database compiled by the University of California Irvine, the University of Michigan Law School and Michigan State University College of Law.

They were there because of false confessions, failures to disclose relevant evidence and criminal justice systems lacking reform have led to thousands of wrongful prosecutions, said Suter, an attorney in the Office of the Public Defender.

“It’s not just one factor,” said Suter, also the director of the Innocence Project Clinic in Baltimore. “It’s a function of how our system was designed.”

Syed was freed after a Baltimore City Circuit Court judge ruled the prosecution had withheld critical evidence at his trial that could have prevented his conviction.

Syed’s release points to the prevalence of such prosecutorial conduct. In Baltimore, 80% of recorded exonerations involved the state withholding evidence, Suter said.

In 2021, there were 161 exonerations in the U.S., and in 102 of those cases, official misconduct occurred, according to the national registry. Of the 102 cases with official misconduct, 59 were homicide cases.

When prosecutorial misconduct is found, seldom are there repercussions, according to studies.

The Chicago Tribune, one of the nation’s premiere publications, looked into 11,000 homicide cases nationwide between 1963 and 1999 with prosecutorial misconduct. The publication found that out of the cases with substantial prosecutorial misconduct, “not a single state disciplinary agency publicly sanctioned any of the prosecutors,” according to the The Innocence Project’s Prosecutorial Oversight report.

The Liman Prosecutorial Misconduct Research Project at Yale University conducted a study that surveyed disciplinary practices and ethical rules of the 50 states and Washington, D.C., and found that the workers who are most likely to find prosecutorial misconduct, such as prosecutors and defense attorneys, do not report it because they work in “a culture that does not support reporting, poor administrative processes and professional disincentives,” according to the oversight report.

There may or may not be repercussions in Syed’s case, said State’s Attorney for Baltimore Marilyn Mosby. Part of the reason is establishing intent from the prosecutor, she said.

“Sometimes it’s due to negligence,” Mosby said. “Sometimes it’s intentional. It’s really difficult to prove an intentional sort of misconduct.

“I have not yet seen any vindictive prosecution. I haven’t seen any sort of charges or appeals that are lodged against prosecutors. You have to establish intent and oftentimes negligence is not criminal intent.”

Arrested at 17 for allegedly killing his girlfriend, Hae Min Lee, Syed could have spent the rest of his life in prison, if it weren’t for Maryland’s Juvenile Restoration Act.

Passed by the General Assembly in 2021, the law says individuals who were arrested at the time of the crime as a juvenile and have served at least 20 years, can request the court to take another look at their sentence.

Syed remains under house detention for the next 27 days, awaiting a decision from Mosby’s office whether he will be retried or exonerated.

In an interview with Capital News Service, Mosby said her decision is dependent on the outcome of the DNA evidence connected with Syed’s case.

“If the DNA comes back and it’s some other person, then clearly, I’m going to go in and I’m going to certify his innocence,” she said. “But if it comes back to him, then that’s a consideration, in light of all the negative contributing factors that we utilize to ask for a new trial.”

Suter said she expects to see a new trial date set for 2023, because the state must decide within 30 days from Syed’s release Monday whether to retry the case, and the results of the tests of the DNA evidence probably will not be back before then. A new trial date, however, does not mean the state will retry Syed.

Even if the case is dropped, Syed will have spent more than half of his life in prison.

Burner said nothing could make up his time spent in prison. He spent half of his life behind bars based on five false, and ever-changing testimonies of one witness who placed him at a Washington, D.C., crime scene, he said.

In Burner’s case, he was released from prison because of the Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act of 2016, which allows for people who were under 18 years of age at the time of the crime to petition the court for a retrial after they served at least 15 years.

He was convicted in 1994 for a murder he did not commit and sentenced to 30 years to life in prison.

“I lay [in prison] multiple times a day, and I just sit there, and to be quite frank, in my mind, I will say, I wish that I did actually do it, because for me, that would have satisfied my conscience that I was in there for a reason,” Burner said.

At the time of his conviction, Burner said he was an amateur boxer with the hope of going professional. He was also working for the Department of Public and Assisted Housing, now the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. He was one month away from being certified in home building and maintenance repair, he said.

His hopes and dreams were crushed after being convicted, he said.

“Going into the courtroom, I can still remember today and hear the screams from my mom,” Burner said. “I went in feeling like a dead-beat, and that I failed in a lot of ways.”

Burner was released on parole in 2018 and was exonerated of his charges in March 2020.

Under Washington, D.C.’s compensation bill, Burner should have received $200,000 for every year spent in prison. A portion of Burner’s compensation was devoted to the Venable-Burner Exoneree Support Fund, which provides financing to hire mentors and navigators for exonerees to help them re-enter the world after being released from prison, he said.

Under Maryland’s exoneree compensation law, which went into effect July 1, 2022, Syed would receive the state’s median annual income for each year he was imprisoned.

Burner said he found his purpose working with the Justice Policy Institute and the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project, advocating and building awareness for people like himself who were wrongfully convicted.

“I’m a fighter by nature,” Burner said. “So, I understand when you lose that hope you lose yourself. So, being here now, I just try to be and create and show that hope that guys [who] aspire to one day, see the world again, that they got somebody out here working for them.”

Republished with permission from MarylandReporter.com

Capital News Service is a student-powered news organization run by the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism. With bureaus in Annapolis and Washington run by professional journalists with decades of experience, they deliver news in multiple formats via partner news organizations and a destination Website.