Protesters decry potential new restrictions on abortion

Capital News Service

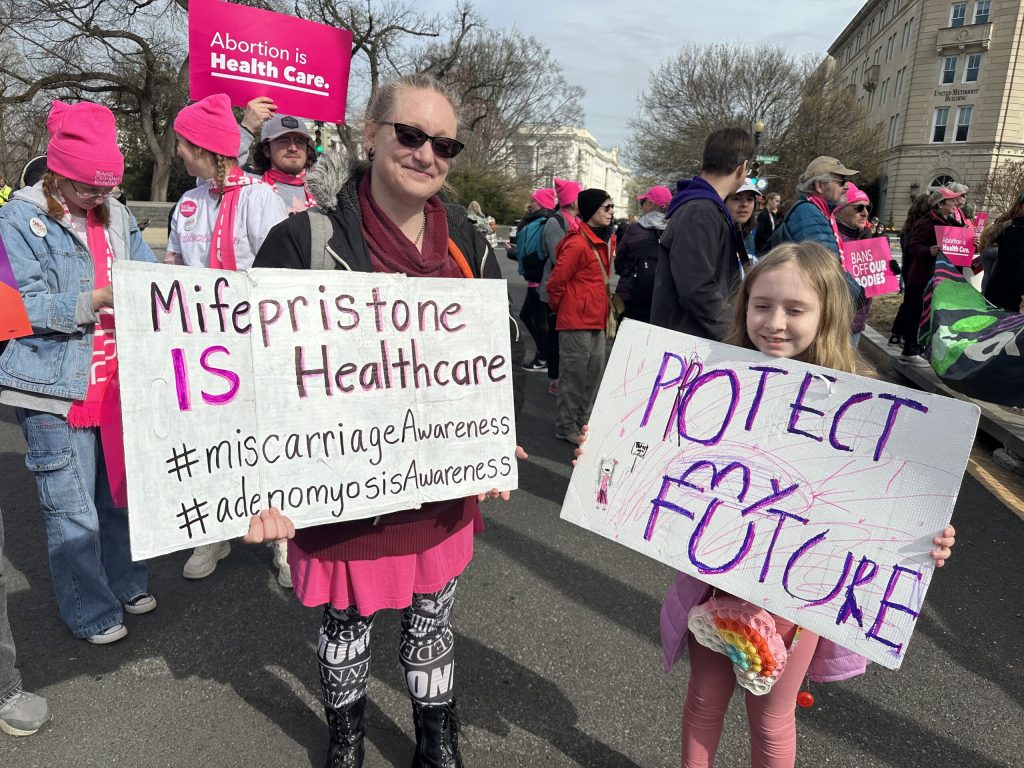

WASHINGTON – Fifteen years ago, mifepristone saved Laura Clime-Coates’s dream of becoming a mother.

The Baltimore woman had a miscarriage and needed medication to expel the nonviable fetus, she said in an interview with Capital News Service. If Clime-Coates hadn’t had access to this medication to end her painful ordeal and save her uterus, she said, she might have not been able to have her daughter.

On Tuesday, Clime-Coates stood alongside that daughter, a third-grader, and hundreds of pro-abortion protesters outside of the Supreme Court. They called on the court to protect mifepristone, a commonly-used abortion drug, which is at the center of a legal battle between the federal Food and Federal Drug Administration and anti-abortion activists.

“I was able to have her because my uterus was spared,” Clime-Coates said, looking at her daughter. “We need to fight for our rights so that one day, if she needs to take it, it will still be available.”

Opponents of the drug say the pill is unsafe and are against the widespread use of the medication. The court’s ruling could impact the entire country, Planned Parenthood representatives said, including states where abortion rights are protected.

The FDA approved mifepristone in 2000 to be used within the first seven weeks of pregnancy. The approval later expanded in 2016 into the 10th week of pregnancy and in 2021 to allow the pill to be administered without a doctor, opening the door for telemedicine abortions.

The Supreme Court is expected to rule whether the regulations around mifepristone should be moved back to the original regulations, without telemedicine and limited to seven weeks.

If the Supreme Court were to rule against the FDA, rural Marylanders and other marginalized communities would bear a large share of the impact, Erin Bradley, vice president of public affairs for Planned Parenthood Maryland, told CNS outside the nation’s highest court.

A majority of Maryland counties do not have an abortion clinic, Bradley said. The 2021 change opened the doors for mailed mifepristone, something Bradley said makes it easier for people who live far from clinics, work hourly jobs or struggle to find transportation to access the medication.

“It allows people to exercise their rights when they want to, how they want to and most conveniently,” Bradley said.

On the plaza in front of the Supreme Court, the crowd of protestors on both sides chanted, gave speeches and sang.

Montgomery County resident Darcy Nair was also standing with her young daughter. The pair were each dressed as suffragettes, holding signs above their heads that read “My Body My Choice.”

Nair started participating in protests in 2017, sensing that abortion and other issues she cared about hung in the balance. When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, Nair said that it felt like a basic civil right was being stripped away.

“I grew up being told that this was a place where I had personal freedom,” Nair said. “I just couldn’t believe it.”

This case is just the next battleground in the court’s fight to chip away abortion access, Nair said.

On the other side of the crowd, a group of anti-mifepristone protesters from Texas and the District of Columbia held up signs accusing the FDA of not protecting women’s health. Among these protestors was Texas resident Catherine Herring.

Herring’s husband pleaded guilty to poisoning her drinks with abortion pills, she said. She called the drug dangerous and said that it landed her in the emergency room.

“I just think it’s important for the FDA to support women, protect women,” Herring said. “Get the information out there that this is dangerous, and that there are side effects that occur when consuming chemical abortion.”

Largo, Maryland, resident Leslie Page, who was standing near the anti-mifepristone protestors, said she doesn’t understand the activists, specifically young women, protesting against the pill.

“I don’t think any woman takes having an abortion lightly,” Page said. “They make a decision based on their circumstances, their life. How can somebody else tell them what to do?”

Capital News Service is a student-powered news organization run by the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism. With bureaus in Annapolis and Washington run by professional journalists with decades of experience, they deliver news in multiple formats via partner news organizations and a destination Website.