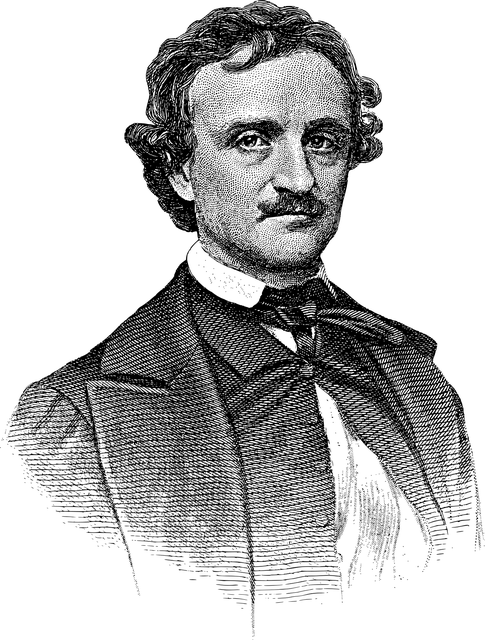

Poe’s Helen of a Thousand Dreams

Photo by Mel Poole on Unsplash

Baltimore may be the city most famously associated with Edgar Allan Poe, but the literary icon was born in Boston, grew up in Richmond, and penned many of his best-known poems and short stories in New York and Philadelphia.

For a brief spell toward the end of his life, the master of the macabre also claimed another Northeast city as his haunt: Providence, Rhode Island. And while Poe’s dark tales of the supernatural may make him a Halloween favorite, his stint in Providence is a story fit for a more sentimental holiday—Valentine’s Day.

Poe came to Providence to court Sarah Helen Whitman, a poet and critic well known in the literary circles of her day. The two exchanged poems and impassioned letters, and Poe proposed to Whitman three days after their first meeting. “That our souls are one, every line of which you have written asserts,” Poe rhapsodized in an October 1848 letter. But the romance was short-lived. In December 1848, three months after their first meeting, the engagement was broken. Less than a year later, on October 7, 1849, Poe died in Baltimore at the age of 40.

A First Encounter

Though he did not meet Whitman until 1848, Poe claimed to have caught his first glimpse of the Providence poet three years earlier, an occasion he later commemorated in a poem sent to Whitman at the beginning of their courtship.

“I saw thee once—once only—years ago,” Poe wrote of that sultry night in July 1845 when, in town for a speaking engagement, he left his hotel for a midnight stroll and chanced upon the woman who would later become his fiancée.

By her own account, Whitman was standing either on the sidewalk or in the doorway of her house on the corner of Benefit and Church Streets on Providence’s East Side, but in his poem Poe evoked a more romantic setting, picturing her in a moonlit garden filled with roses:

Clad all in white, upon a violet bank

I saw thee half reclining; while the moon

Fell on the upturn’d faces of the roses

Already an admirer of her published verses, Poe was able to recognize Whitman and to identify the house as her own through the descriptions of a mutual friend. Yet, convinced that Whitman was happily married, Poe avoided meeting her, even provoking a quarrel the next day by refusing to accompany a friend to Whitman’s house.

“I dared not speak of you—much less see you,” Poe explained in an 1848 letter. “For years your name never passed my lips, while my soul drank in, with a delirious thirst, all that was uttered in my presence respecting you.”

At the time of Poe’s midnight sighting, Whitman was not, in fact, a married woman, but a widow of over ten years. In 1828, she had married lawyer and writer John Winslow Whitman and moved with him to Boston, where she published her first poems—under the signature of “Helen,” the name by which Poe would later call her.

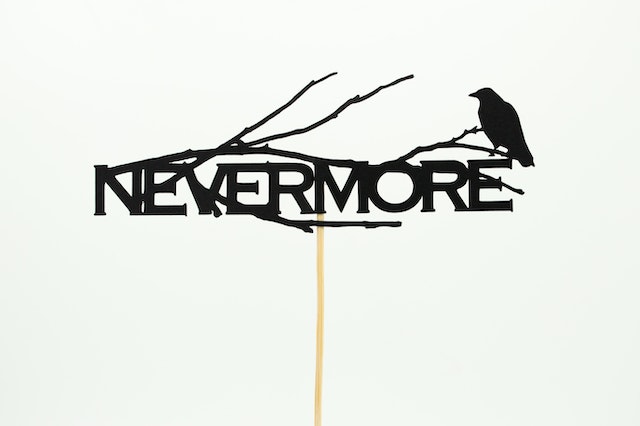

But upon her husband’s death in 1833, Whitman returned to Providence to live with her mother and sister, where she continued her literary output, cultivated an interest in spiritualism and transcendentalism, and participated in various progressive causes of the day, including the universal suffrage movement. She also became an avid fan of the writings of Poe, who by 1845 had reached worldwide literary fame with the publication of his poem “The Raven.”

Three years later, Whitman’s enthusiasm for Poe’s work would be the catalyst for their love affair—a brief but intense romance that would begin, not with another moonlit encounter, but with an exchange of verses.

Roses Are Red, Ravens Are True…

On February 14, 1848, Anne Lynch, a wealthy New York socialite active in literary circles, held a Valentine’s party at her residence and invited Whitman to contribute a poem to be read at the gathering. Whitman’s contribution was an admiring tribute to Poe, addressed to him in the persona of the “grim and ancient Raven” from his famous poem. Her last stanza ends on an intimate note:

Wilt thou to my heart and ear

Be a Raven true as ever

Flapped his wings and croaked “Despair”?

Not a bird that roams the forest

Shall our lofty eyrie share.

Recently widowed (and presumably by then better informed about Whitman’s own marital status), Poe reciprocated with verses of his own, first sending her a copy of one of his earliest poems—his 1831 “To Helen,” written for an idealized boyhood love—and then composing his second “To Helen” immortalizing his midnight glimpse of Whitman three years earlier.

In September 1848, Poe secured a formal letter of introduction from a mutual acquaintance and visited Whitman in her Providence home for the first time. “Your hand rested in mine, and my whole soul shook with a tremulous ecstasy,” Poe wrote of their first meeting. “I saw that you were Helen—my Helen—the Helen of a thousand dreams.”

During Poe’s first visit, he and Whitman spent three days in each other’s company, passing much of their time at the Providence Athenaeum, an independent lending library founded in 1753. The Athenaeum still has in its collection a December 1847 edition of the American Review in which Poe, on one of his visits with Whitman, signed his initials next to his anonymously published poem “Ulalume.” Before leaving town, Poe proposed to Whitman on the grounds of Swan Point Cemetery on the East Side of Providence—the cemetery where, almost a century later, fellow horror writer H.P. Lovecraft would be buried.

A Broken Promise and a Broken Engagement

Whitman initially declined Poe’s marriage proposal, citing her age and poor health as reasons. (She and Poe shared the same birthday of January 19, but at 45 years old she was six years his senior.) “Had I youth and beauty, I would live for you and die with you,” she wrote to him. “Now were I to allow myself to love you, I would only enjoy a bright, brief hour of rapture and die.”

But Whitman also had another reason to be hesitant to marry Poe. Furnished with reports from acquaintances of his erratic behavior and abuse of alcohol, Whitman was under pressure from both family and friends to keep him at a distance.

In the ensuing weeks, Poe wrote ardent letters urging her to reconsider his proposal, made several trips to Providence to plead his love, and apparently attempted to commit suicide by taking a heavy dose of laudanum, an opium-based painkiller. But by November, Whitman had agreed to a betrothal—on condition that Poe would abstain from alcohol.

Subsequent events unfolded quickly. By December 15, realizing that her daughter was intent on marrying Poe, Whitman’s mother signed legal documents to ensure that her prospective son-in-law would not have access to the funds of her modest estate.

On December 21, the day after Poe delivered a highly successful lecture on “The Poetic Principle” before an audience of 1,800 people at the Providence Lyceum, Whitman agreed to an immediate marriage. And on December 23, Poe sent word to the minister of St. John’s Episcopal Church to publish their banns of matrimony. But before the day was out, Whitman received an anonymous note informing her that Poe had already broken his promise to stop drinking. The engagement was off.

Two years later, Whitman described her final hours with Poe in a letter to a friend. “I felt utterly helpless of being able to exercise any permanent influence over his life,” she wrote of her reaction to learning of Poe’s broken promise. “He earnestly endeavored to persuade me that I had been misinformed … and to win from me an assurance that our parting should not be a final one,” she explained in her 1850 letter.

But Whitman’s mother—on whom she was both financially and emotionally dependent—took matters into her own hands, “insisting upon the immediate termination of the interview.” Complaining bitterly of the “intolerable insults” of her family, Poe left Providence on a 6:00 p.m. train, never again to see his Helen of a thousand dreams.

Elisabeth Herschbach lives with her husband, son, and Jack Russell terrier in Prince George’s County, Maryland, where she works as a copy editor and occasional writer and translator.

This is exactly what I was looking for. Thanks for sharing.