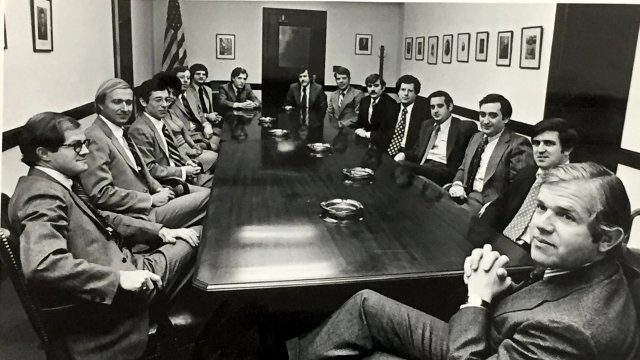

Lost lessons from George Beall

George Beall (lower right corner) in a 1975 meeting with U.S. Attorneys in Maryland. (Courtesy U.S. Attorney Office in Baltimore.)

This column is republished with permission from Talk Media News.

George Beall got away from us a few days ago, just when America needed him most. In Washington the Democrats and the Republicans divide each other strictly along rigid party lines which no one dares cross.

But Beall thought there were some things more important than party, and one of them was political integrity.

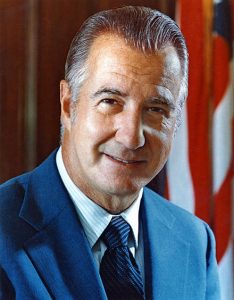

The obituaries last week all rightfully connected Beall with the downfall of Spiro Agnew. But they barely touched on the pressure Beall felt as he went after Richard Nixon’s outlaw vice president, and how Beall stood up to it, and how he had to overcome generations of family loyalty to the Republican Party.

Beall was U.S. attorney for Baltimore when his office got word that Agnew was taking money under the table. No one in America in the early 1970s could have imagined such a thing.

Agnew postured himself as Mr. Clean. He’d been Baltimore County executive. He’d been governor of Maryland. Then he became Nixon’s vice president and designated attack dog.

He was one of the great divisive figures of his explosive era. If he wasn’t blaming black political leaders and clergy for the riots that followed Martin Luther King’s assassination, he was barking insults at those who protested the endless war in Vietnam, or those who simply wore their hair too long, or reporters who dared write critically about Republicans.

Agnew pretended to be above all human failing. He used multi-syllable words to show off his vocabulary – and his bile. “Nattering nabobs of negativity,” he famously called reporters.

He dressed impeccably, and nailed every hair into place. He talked the good talk about honesty, but through all his years of political office – including the White House years – he was routinely extorting thousands of dollars in little white envelopes from those wishing to do business with the government.

When Beall started getting reports on this, he knew immediately the political bind in which he’d been placed.

His father, J. Glenn Beall, had been a Republican U.S. senator. His brother, J. Glenn Beall Jr., was a Republican U.S. senator. Political party meant something to this family.

Honesty meant more.

But family history was only part of it. As his office’s investigation heated up, Beall started getting phone calls from the Nixon White House. They wanted him to drop it, to let Agnew slip away. Beall did not cave.

To this day, those who were there with him – assistant prosecutors like Barney Skolnik and Ron Liebman who worked on the Agnew case – insist that Beall never wavered, and never even hinted to them at the pressure he was under.

And then came the day when Agnew was finally brought to justice. In a jam-packed federal courthouse in Baltimore, he pleaded nolo contendere – no contest – to tax evasion charges and then walked off into the shadows, the only vice president in history ever forced from office, his crimes quickly forgotten as the country braced itself for the coming Watergate scandals.

Later that year, sitting in his courthouse office, Beall invited me in and talked about the emotional after-effects of the Agnew pursuit.

He said he’d lie in bed for hours and fail to find sleep. He couldn’t downshift his emotions. For months, when he’d finally drift off, his sleep was accompanied by nightmares. Then he’d awaken in a sweat, fears and anxieties finally catching up to him.

But he was comforted knowing he’d done the right thing.

In our time, party allegiance appears more important than love of country to those wishing to hold onto Washington political power. In our time, when intelligence agencies are said to be investigating connections between the new president’s inner circle and Vladimir Putin’s, we wonder if political alliances will stand in the way.

The pity of it is that so few people recall the great lesson of George Beall.

But, what the hell, how many even remember Spiro Agnew?

Michael Olesker, columnist for the News American, Baltimore Sun, and Baltimore Examiner has spent a quarter of a century writing about the city he loves.He is the author of several books, including Michael Olesker’s Baltimore: If You Live Here, You’re Home, Journeys to the Heart of Baltimore, and The Colts’ Baltimore: A City and Its Love Affair in the 1950s, all published by Johns Hopkins Press.