Jim Burger: Retrospective offers fascinating focus on ‘A Charmed Life’

Photographer Jim Burger is joined at his opening by niece Jessica Parker and sister Pauly Heller. (Anthony C. Hayes)

I have been friends with photographer/artist Jim Burger for about eight years now. We are two of the younger members of Baltimore’s Aging Newspapermen’s Club and amongst the handful of old-school journalists still plying their trade here in Charm City. I open with this personal disclaimer, because I should. But said camaraderie ought to come as no surprise to anyone in our ever-dwindling local newsrooms, or at the bar of the Mt. Royal Tavern. Jim Burger has an awful lot of friends here in Baltimore. That was certainly clear last Saturday night, as an overflowing crowd packed into the Creative Alliance for the opening of “A Charmed Life – The Jim Burger Photography Retrospective.”

Curated in collaboration with Creative Alliance Executive Director Gina Caruso, “A Charmed Life” is the first comprehensive retrospective of Burger’s 35-year career, first as a photo major at the Maryland Institute College of Art, then as a photojournalist at the Baltimore City Paper and the Baltimore Sun.

Along with the photography from his newspaper endeavors, Burger has also collaborated on many books, including two with former Sun food writer Rob Kasper (Baltimore Beer: A Satisfying History of Charm City Brewing) and legendary Orioles first baseman Boog Powell (Baltimore Baseball and Barbeque with Boog Powell.) He is also one of the cofounders of the annual arts and eating exhibition, Foodscape. Not surprisingly, Jim is one of the area’s most in-demand free-lance artists.

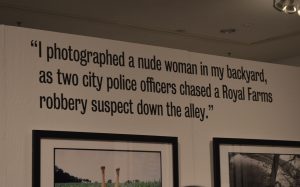

In the exhibition statement, Burger modestly offers: “I have tramped the streets and alleyways of Baltimore, Maryland. With my camera and a notepad, I have documented its citizens. There’s a hidden beauty, a charm, to Baltimore and Baltimoreans. To be sure, there is pain and pleasure, triumph and defeat in daily life here, but just below the surface, a quiet, humorous stoicism. I try to capture that essence when I shoot. Occasionally, in the past, I was presented with opportunities to leave Baltimore. These photos show why I always said no.”

We caught up with Burger the morning after the morning after his show opening. Given Jim’s whirlwind schedule, to try to catch up with him any sooner may have pushed the bounds of our friendship.

* * * * *

BPE: Let me begin by asking: Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?

JB: (laughing) Yes to both! But I’m no longer an officer. I got busy last year.

BPE: I’d really like to start by asking a bit about your background. You’re from Pittsburgh?

JB: I’m from near Pittsburgh. Uniontown, PA. It’s near striking distance. A lot of people in my town worked in Pittsburgh; it’s that close.

BPE: Steel workers?

JB: Steel and coal miners. Coal mining was really big in the area near my town.

BPE: And your father was a pub owner?

JB: Yes, a bar owner.

BPE: Is that what got you interested in the bar business?

JB: That’s what got me UN-interested in the bar business. I worked for him for many years, washing dishes and doing all of the dirty jobs, then eventually tending bar. All that made me not want to own a bar.

I know the exact day I moved to Baltimore, because all I have to do is look at my high school diploma. I graduated on May 30, 1978 and I moved to Baltimore on May 31st, 1978. I wanted to get away. To get that distance from my father, Lenny Burger, who I loved. I really adored him, but I just didn’t want to work in a bar.

I have two sisters and a brother, and they were all here for the show opening. That’s actually one of the reasons I wanted to do a retrospective.

There’s a photo downstairs on my wall of three of us, and it was shot in 2009 in the basement of the synagogue in Uniontown, after my mother’s funeral. That was the last time the four of us had all been together. We had missed some opportunities, and I thought, “This is just crazy.” I wanted to get together with them for a happy occasion. So that was a big part of why I did this.

BPE: You arrived in Baltimore in 1978 with the hopes of becoming an illustrator?

JB: Yeah, the strength of my portfolio to get into the Maryland Institute was in illustration. That’s mostly what I showed. I showed some photographs, too. I was a photographer for the yearbook in junior high and high school, but it never really occurred to me that I might want to do that. I got into school, and I was the best artist at Uniontown Sr. High. Then I got to the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), and I was in a building full of the best artists from everywhere. I wasn’t as good as some of these other guys. And then, as fate would have it, Richard Kristel – who taught photography – took me under his wing. He was an excellent teacher and became my mentor in school. Very quickly, after a lifetime of drawing, I veered away from illustration and concentrated on photography. That was the best thing that ever happened to me.

BPE: What sort of photography did you do while you were in school?

JB: At the Maryland Institute, there are foundational courses before you get into the more specialized fields. I learned how to work a view camera in large format photography, and one of my signature photos is hanging at the Peabody Library. But I really started pushing toward documentary work. I liked people pictures and social documentary. There was one called Fantasy in Photography and Sequential Imagery. That’s more about photographing people.

I just really fell in love with Baltimore and the people of this city.

As a natural progression – and I’m really not sure why I did this – I chose to photograph the Baltimore City Fire Department for my senior thesis. That was a real adventure.

I had a run of the department and photographed every aspect you can imagine. Then I teamed up with another photographer, named Frank Rehak, who was already out of school. My thesis was separate, but Frank and I combined our photographs for a show at the City Hall Gallery. And that became our book, In Service: A Documentary of the Baltimore City Fire Department. Mike Anft, who worked with me at the City Paper, wrote the text for it.

BPE: So, you graduated from MICA in 1982. Did you go to work immediately for the City Paper?

JB: Yes. There was fellow there by the name of Barry Holniker. He was a schoolmate of mine but a year ahead of me. He was also working at the City Paper with another photographer, Jennifer Bishop. They were the only two photographers on staff at that time.

Now, the City Paper was experiencing tremendous growth. Jennifer and Barry shot every photo for every issue, and they were starting to burn out. They figured they needed a third photographer, and Barry thought I’d be a good fit. He asked me to put together a portfolio to show to the art director and the senior staff.

Barry was right – I was a good fit. You want to talk about a big break? And I have had some big breaks – just permission to shoot the Fire Department!

It was right at the end of that era, where you sign a waiver and ride on the apparatus. That wasn’t for just anybody that walked through the door. But television crews would ride along, or some fire buff who would always join them. They could do that.

Frank was also instrumental in getting me in. I think he taught the chief’s son, so there was a connection. We got helmets – I’ve still got my helmet – and turnout gear and boots. They put notices in all the fire houses that Jim Burger and Frank Rehak would be out there somewhere, so please welcome them. It wasn’t an order, and some houses really opened up to us.

Because I was working on my thesis, I was out a lot, and I shot a lot. As luck would have it, right down the street from MICA, at North Ave and Mt Royal, was Engine 1 Truck 11. The house was really a good fire house and it stayed pretty busy. I could stay there, and in the morning just walk to school. Sometimes I would go to school dog tired, and I had other classes, but at the end, we had a comprehensive view of the Fire Department, so that worked out well.

BPE: You still have faith in the Fire Department?

JB: I do! Though, after it was done, I often joked that I wouldn’t cross the street to watch a house burn down.

BPE: Are you still in touch with any of the firemen?

JB. Two of them – who happen to be the subjects of two of the iconic photos from that project – were at the opening last Saturday night. Captain Fred Rafferty was there. It was his boots that can be seen crawling in under a wall of smoke. And then the shot, which was on the cover of the book, is of Jimmie Hayes – the fireman with a handkerchief dabbing glass from a blown out window out of his eye.

I couldn’t help but notice in the cacophony of a pretty crowded room, the mass of people who were planted in front of those fire photos. They’re pretty captivating.

BPE: How long were you at the City Paper?

JB: I worked there for six years, and I shot a lot. Now, that wasn’t a full-time job, because there were no full time jobs at the City Paper. I did other things, but that was when the Fire Department book was published.

As luck would have it, in 1988, the Sun had an opening for a photographer in their marketing department. That too was the end of an era, because they just looked around locally and said, “Who can we get? What about Jim Burger? He did that book about the Fire Department.” They called me, and within a week, I was hired.

I went to work for the Baltimore Sun, and I never looked back. Ten very happy years.

BPE: But you did have fun working at the City Paper?

JB: Absolutely. You know, the City Paper may have started out as a souped-up college newspaper, but it didn’t take them long to really start to make a difference. It got to be very thick and very influential. You saw other alternative papers around, and everyone was chasing The Village Voice, but they were doing the kind of feature pieces that nobody else was doing.

When I started with the Sun, I thought “This is it!” But a lot changed in ten years. It was the sort of place where, once you got there, you could just work your entire career. The building was full of people like that. They started there younger than I and worked to full retirement.

I thought that would be it, but the industry sort of shifted, and in 1999 I was offered an early retirement deal. It was a formula designed to get rid of the old timers, and I fell into it. Everybody said, “Oh, Jim Burger won’t take it. He loves it here,” which was true. But I talked it over with my wife, and I had some time to think about it. I also had some quiet conversations with art directors around town about freelance positions, and they said, “Oh, if you leave the Sun, I’ll hire you.” So, on the last day I signed up to take the retirement package, and kinda shocked the Sun.

In every buy-out agreement, they say you can’t come back. They waived that immediately for me, and for many years thereafter, the Sun would call me for special projects, or if something got messed up, they would give it to me. I would shoot things and just send them a bill. They were a very good client. In the meantime, I picked up a lot of other clients, so as a commercial photographer, I do exceedingly well.

BPE: Stories that stick out in your mind?

JB: There are lots of them.

BPE: Isn’t there one about you spreading the ashes of a dead friend with Rafael Alvarez?

JB: You’d have to check it out with Rafael, because he’d remember it better – or not. At least he would tell it better.

We were charged with spreading David Klein’s ashes. We were good friends, but David and Rafael were great friends. Just a great artist. Rafael was given some of Klein’s ashes. We never called him David – it was always Klein.

As you know, Rafael has three row homes in Greektown. He put the ashes somewhere for safe keeping and then immediately forgot where they were. When it came time to spread them, he couldn’t find them. A lot of time passed – maybe a year or more? When he finally found them, I said, “Don’t put them down!” So, he came over here.

What we were going to do was scatter them in a place that meant something to Klein. Maybe his old backyard? Rafael came over here, and we had breakfast and planned the whole thing. We were going to say the Mourner’s Kaddish, which is the Hebrew prayer for the dead, and I’d like to think we were going to do it with some dignity. We had yarmulkes and the prayer all written out. We were ready to go.

So, we drive over to Klein’s old neighborhood and discover that everything was torn down. I mean, there was nothing left. They had built over everything!

I’ve got a number of ashes stories, but this was unique. We finally found a suitable place and, as I said, we did do it with dignity. I photographed Rafael, and he wrote it up for the Sun.

BPE: How would you compare shooting for the City Paper vs the Sun?

JB: The City Paper was pretty unbridled. Their editorial policy as far as photography was they had no editorial policy. You had to really grab the reader. They were very visual and over the top. That’s why I fell in with Barry and Jennifer. We had that sort of tilted view of everything. A lot of photos for the retrospective were drawn from that era.

I think, when I went to the Sun, it was fun for them to have a photographer who had graduated from MICA – Home of the Fighting Palettes – undefeated in football since 1826. It was also fun to have a photographer who had worked for the City Paper. But they made it quite clear that that sort of free-wheeling stuff was not gonna fly there. I tried early on, and they asked, “Are you out of you mind?” I said okay and did whatever they asked, because I wanted to work there. And I loved it.

I named the show “A Charmed Life” because I’ve lived one. But my styles really had to change.

BPE: You worked with Gina Caruso at the Creative Alliance to narrow this collection down to about 130 photos. Please tell us about that.

JB: Years ago, I started to think about my legacy. I had seen other photographers pass away, and when friends went into their studios with the idea of looking at the negatives for doing a tribute show, they didn’t know where to start. They didn’t know the order or what photos meant anything to the photographer. If they even did the show, you’d walk away asking, “You mean, this is it???”

I decided to start an archive of what my favorite work is. I’d say, “If you go to this hard drive, you will find the photos that meant something to me.” So I started going through all of my old negatives, and just started scanning the ones that really meant something to me. After that, I said that I would write the stories behind them and embed them in the photos. In the process of doing that, I found some real gems. I found photos that I shot that were never printed. These photos just languished in files for many years. I’m talking about hundreds of thousands of photos, because I’ve been around for a while.

Eventually, the archive grew to 400-plus photos. A few people knew about it, including Gina, and she wanted to see it. She and Jeremy Stern came over, and they sat down at my computer and flipped through the archive. They made the decision that day to give me a one man show, which was quite an honor.

They trimmed it down to accommodate the retrospective for the size of the room, but there are photos in that show that I have never seen printed.

There are four photos of the Fish Market from a story Mike Anft and I did for the City Paper that ran maybe 3″x4″ inches, and here they are 30″x40″ and beautifully framed. That’s the thrill for me, is seeing the work up like that. And I’m getting great feedback from everyone who has seen the show

BPE: Having covered other art shows around town, where you might have had one or two pieces on display, one observation I’ve made about your work is that you definitely have a following here in Baltimore.

JB: I’ve been very fortunate in that respect. There are people in town who like certain things. Some collect my nudes – very quietly – but they like them, and I enjoy doing them, though I don’t shoot nudes all that often.

Most of the nudes in my retrospective are from Foodscape, and they are all done in fun. Over the years, I’ve shot nudes on commission, and they were off limits. But the shot of the woman with the cello – that was done on commission sometime in the early 90s. Afterwards, I told her I would really like to put it in a show. She said, “Oh, nooooooooo.”

When I was offered the retrospective, I contacted her. A lot of time had gone by, and her attitude has completely changed. She said, “Yes, put it up.” Unfortunately, she was out of town and couldn’t make it to the opening, but we’re planning on getting together sometime during the run of the show.

By the way, I believe that photo sold on opening night, but there are still some great bargains out there, and Jim Burger photos make great Christmas gifts.

BPE: They would make great gifts. I was thinking of purchasing the shot of Conrad Brooks for some friends of mine who cared for him in his declining years. Who did the printing and framing?

JB: Tom Stone at JLP Framing did the framing. Brian Miller at Full Circle did all of the color and the larger sized prints. Once everything was all approved, I came over and spent a couple of days signing them.

BPE: Getting back for a minute to the nudes, please tell us about the marriage of these unknown models and Natty Boh.

JB: You know, I really like National Bohemian beer. It was just so iconic. For whatever reason, I just used it as a prop because Foodscape was always about food. National Bohemian is very popular – especially with young people. I’ve done about ten nudes with Natty Boh as the main prop, and people just collect them. I mean, this is Baltimore and they are so campy, and it’s all in good fun.

Anyone who knows me knows that, for one thing, I don’t use professional models. They’re all amateurs, and it sort of feeds upon itself. Women will come up to me at Foodscape and ask how I get the models, then say, “Oh, I could never do that.” But here’s how it works, and this is the standard agreement. If you want me to shoot you, we do this anonymously for Foodscape. If you do it, I will give you your own private photo session, and I will photograph you, your portrait, your family, your children, or we’ll do another nude. That is all for you, and no one else will see it. And everyone of them says, “Really? You will photograph my children?” I say, “Absolutely, and there is one more thing. If I take one photo of you for Foodscape and you’re uncomfortable, then we will stop and throw the film away or erase everything and you will still get your private photo session.”

Everyone of them – including the women who asked if I would really photograph their children – has asked for another nude.

BPE: Is that on the record?

JB: Absolutely. Everyone knows this. And back in the day I would give them the film to do whatever they wanted with it. Now, I burn them a disc on my laptop and then show them the screen, as I delete the files from my computer. That’s how it always goes down.

I promise them anonymity, and I have always kept that promise, though it’s funny. One model showed up at an opening with about 20 of her friends. Even so, I won’t reveal or confirm a model’s name.

BPE: You don’t shoot girls with ink?

JB: I don’t like to. First of all, I’m not a big fan of tattoos. Maybe it’s because I’m Jewish, and Jews don’t get tattoos. But also, when you photograph someone with a tattoo, that’s the first thing that you see. That’s just where your eyes go. I want people looking at my photo.

I avoid photographing signs. I don’t like photographing someone wearing a t-shirt that says…

BPE: Maryland Institute College of Art?

JB: (laughing) Exactly. If it doesn’t add to the photo, it detracts. And that’s why I just don’t like it.

BPE: Tell us about Conrad Brooks.

JB: Oh, Conrad. Well, Conrad was an uncle of Gerry Smolinski – a guy who worked at the Sun. Gerry and I used to go out drinking together. When I was a kid, I saw Plan 9 From Outer Space. I just thought it was so awful and so much fun. They made a movie about Plan 9 From Outer Space called Ed Wood, and when that film came out, Gerry told me about his uncle and said that Conrad had a small part in Ed Wood. Gerry said, “My uncle was in Plan 9 From Outer Space.” I wanted to meet him, and Gerry said, “Well, just write him a letter and I’ll get it to him,” So, Gerry would go off to these family functions, and Uncle Conrad wouldn’t show up. Years went by, and I had given up on meeting him.

Eventually, he must have gotten the letter, because he called me in the middle of the night, and said, “Hey, pal, this is Conrad Brooks. I hear you are looking for me!” I woke up the next day and thought, “Did I dream that?” But there was a note by my bed with his phone number on it, so we finally met, and I interviewed him and photographed him, and we became good friends. He was always selling me junk. It cost a lot to be friends with Conrad Brooks.

I would go to visit him – he was living in a trailer in West Virginia – and it was a real adventure just to go and meet him. So much so, that eventually I wrote an entire story about it for Washington Post Magazine. We were good friends, to the point where I would drive there and take him to lunch and the race track. He knew about my retrospective, but of course he died last year. When I do my gallery talk, I’m going to talk about him. That’s one of the photos I’m going to talk about.

When I’d go down there to meet him, I’d say, “I’ll take you to lunch wherever you want to go.” Well, there was a hospital in the area with a cafeteria that he just loved. He knew all of the women there, so they’d give him extra portions, and he would stay busy, chatting people up.

He was an honest-to-God character.

BPE: You’ve had these amazing life experiences and now this wonderful retrospective. Where do you go from here?

JB: I know – where DO I go from here? For the next six weeks, I’ll concentrate on selling the work. I’m doing this gallery talk on Nov. 8. There are some groups who want to come to the gallery and have me there to do some sort of private talks about my work. I’m happy to do that. And then we’ll see how things go.

At some point, maybe publishing a book. But for now, it’s Jim Burger Photography. It’s one o’clock right now. I’ve got a guy coming over at 3:00, and I’m shooting his portrait for LinkedIn. So, I’ve got to work. I’ve got a retrospective to pay for!

BPE: I didn’t want to ask what this is costing you, but now that we’re on that subject…

JB: Let me put it to you this way: The Jim Burger Retrospective is the wedding for the daughter I never had. That’s what it cost, but it was worth it.

What am I gonna do – be buried with my money?

As a commercial photographer, I’ve done very well. (My wife) Sue and I live in this house very comfortably. I wanted people to see the work, and it has been a blast.

But here’s another thing. I had it catered by Parkhurst Catering. They do the food service for the Maryland Institute – first class. I told them, “Money’s no object, and I don’t want to run out of food.” They brought enough food for five hundred people, and at the end of the night, it looked like there was food left for ten.

So that was it.

I had great sponsors. I didn’t ask for any money, but some people just came forward to help see this through. Becky and Stu Cooper, Linda and Jack Lapides, and Nancy and Vic Romita. All put down money, and that was very sweet of them. But then also Sagamore Rye and Lyon Rum; Union Brewing and Waverly Brewing; Checkerspot Brewing, and Bacchus Distributors brought a special rosé. That was quite popular.

BPE: All clients of yours?

JB: At the very least, I sat at their bars.

Let me add that Gloria and Manny Alvarez, and Phoebe Stein and Rafael Alvarez also wrote checks, and that was very, very nice.

BPE: I would have written a check, but it wouldn’t have been any good.

JB: (laughter) That’s okay – I wouldn’t have asked.

BPE: Before we wrap up. Please tell us how readers may purchase your work.

JB: Well, for now, the Creative Alliance is handling sales from the show, and it’s a 60/40 split, which really helps the gallery. After that, God forbid there are still any pieces left over from the show, people can go to my website, which Kevin Lynch just completely updated.

BPE: And they can come and pick the pieces out of your basement?

JB: The basement, from off my ceilings, leaning against the house out in the alley, you name it.

BPE: Thank You.

* * * * *

“A Charmed Life – The Jim Burger Photography Retrospective” runs from now – Nov. 24, 2018. Exhibition hours are Tues – Sat. 11am – 7pm. The Creative Alliance is located at 3134 Eastern Ave. In Baltimore, MD.

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”