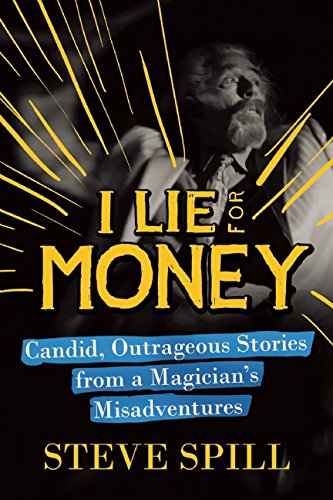

I Lie for Money: Candid, Outrageous Stories from a Magician’s Misadventures

The Baltimore Post-Examiner is proud to present an excerpt from magician Steve Spill’s book, “I Lie for Money: Candid, Outrageous Stories from a Magician’s Misadventures.” Spill reveals how he survived decades inside a rarely profitable, offbeat showbiz profession—magic.

Amazon Summary: Spill tells of how his tailor grandfather sewed secret pockets in a magician’s tuxedo back in 1910, which started his childhood dream to become a magician. This dream took Spill on a journey that started with him performing, as a young boy, at a “Beauty on a Budget” neighborhood house party to engagements in Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean, to today in Santa Monica, California, where he’s been starring in his own shows since 1998 at Magicopolis, the theater he designed and built himself.

Being a magician has given Spill the opportunity to interact with the world’s most famous and fascinating people. In his memoir, Spill reveals the many unique encounters that his profession has led him to enjoy and endure: hosting Sting as his opening act one night, spending two days on camera with Joan Rivers, and selling tricks to Bob Dylan, as well as encounters with Adam Sandler, Stephen King, and other celebrities.

I Lie for Money . . . is a literary magic show that captures the highs and lows of an extraordinary life that will delight and amaze you with wit and wickedness. This book should be an obligatory read for anyone considering a creative career, and it serves as an inspiration to those who desire to craft an independent life. The book can be purchased at Amazon.

PART ONE

FIRST BEST JOBS

THE JOLLY JESTER

Aspen, at the top of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, is an internationally famous ski resort and glitzy playground for the affluent. But in 1976 the Aspen vibe was not unlike the frat boy atmosphere depicted in the film Animal House and we would really come alive just after the moon came up. Everybody drank, did drugs, smoked, and made love, with no fear of addiction or disease or death. It seemed we all had permanent erections, hangovers, and everything was carefree and raucous and unplanned. In those days, we had all the fun we could each and every day.

I was twenty-one years old when I started a four-year tour of duty working for Bob Sheets as a magician/bartender at The Jolly Jester. My fancy salary was thirty dollars before taxes per eight-hour shift plus tips. That was, of course, just a starting salary. In slightly over three years my superior talents were recognized and I was upped to thirty-five dollars before taxes per eight-hour shift plus tips. Actually I exaggerated about the eight-hour part, as it was usually longer. The shift started around 4:00 p.m., après-ski time, and went all night to the first hours of the morning till I was unconscious, subconscious, nauseous, or all three.

Bob has always been smart, talented, and inspiring, with a round face, thick neck, twinkly eyes, big moustache, and gap-toothed smile. Mr. Sheets has a sense of the whimsy, a sense of the absurd, and when his imagination takes off and he gets to the child part of himself, he giggles and carries on like a little kid. That’s how he became known as the Jolly Jester—hence th bar’s name. In 1975, Bob had been hired as a bartender just outside Aspen, in Snowmass, at country-pop singer John Denver’s Tower Restaurant.

Sheets quickly became a successful local legend behind the bar, mixing drinks and merriment with his comedy and magic. So much so, that the following winter a patron sponsored Bob and he opened his own bar in Aspen. He knew he couldn’t do it alone—eight hours a day, seven days a week, was too much time for one magician to fill, no matter how talented they were, and would only lead to burnout. As it turned out, we both burned out. But it was a wild ride for the handful of tourist seasons that it lasted.

Bob was a consummate professional who became a valued lifelong friend, and I learned more from him, and the job he gave me, than I realized at the time. One of the great educational benefits from the work was a practical understanding of the art and science of audience management. People who are oiling their throats with alcohol are generally not shy when they see how a trick is done, and it’s a great help to know where corrections are needed. Most of the bar-hopping crowd changed five times a night, which enabled me to perfect tricks by doing them over and over and over, forty or fifty times a week. By trial and error my sleight-of-hand, timing, presentation, and other elements improved.

I absorbed much of what I know about comedy from the bar crowd. I learned to not work too hard at being funny, not to imitate myself from the night before, to try to make each performance as if it were the first time I’d ever done it, how to improvise, how to take advantage of a situation with a quick adlib—like when a guy was at the bar for several hours, drinking continuously, hurling shot after shot against his tonsils, and then, without a word, would fall over backwards onto the floor, out cold. I might say something like “I like a man who knows when to stop.”

Bob also trained me as a bartender and taught me how to use magic to sell more cocktails. “The more you drink, the better the tricks look.” One key strategy that I learned is to never perform a trick until all the drinks are half full. That way, when the trick is over, everyone is ready for a new round. Patrons were unconsciously trained—now it’s time to watch a trick, now it’s time to buy a drink—and Pavlov would have loved it.

Bob also trained me as a bartender and taught me how to use magic to sell more cocktails. “The more you drink, the better the tricks look.” One key strategy that I learned is to never perform a trick until all the drinks are half full. That way, when the trick is over, everyone is ready for a new round. Patrons were unconsciously trained—now it’s time to watch a trick, now it’s time to buy a drink—and Pavlov would have loved it.

“Don’t applaud, keep on drinking,” was a motto I learned quickly.

Bob was, and is, also an amazing street magician. In the early days, Bob stood in front of The Jester and performed his street act. Instead of passing the hat, he pied pipered folks into the bar. Once inside, Bob introduced me. I sold drinks and did tricks, while Bob went outside and gathered another group. In an hour, a big crowd pressed around the bar. Word got around, and after a few days Bob no longer needed to work the street; from then on things just exploded.

The bar was long; that shelf could support at least thirty pairs of elbows. Four feet behind the bar were long benches to sit on with a ledge that ran atop the benches that was just wide enough, if you were young and a little athletic, to stand on. People were sitting at the bar, standing on the floor, sitting on the benches, and standing on top of the benches from one end to the other. And the crowd was wired. Crazed. Insane.

The lights were low, the rock and roll was loud, and we would announce “We’re about to do some magic and there’ll be no drinks for ten minutes, so get ’em now.” To serve everyone would take twenty to thirty minutes. Nobody ever died of thirst at The Jester; even competent drinkers were over-served, and mixing the drinks was a big part of the show.

“Want a lime in that gin & tonic?” I pretended to take a lime out of the wastebasket, washed it off, and dropped it in the drink. “Don’t worry, the alcohol will kill any germs.” When someone ordered a beer we didn’t have, such as Moosehead Ale, Bob responded, “no problemo.” He opened and poured a bottle of Budweiser, and then, with a felt tip pen, crossed out the word “Bud” and wrote “Moosehead.” “One Moosehead, drink up,” he’d say.

We did a substantial business serving upside down margaritas—no glass necessary. Customers laid their heads on the bar, mouths open. With a bottle of Triple Sec in one hand and Roses’s Lime in the other, I poured, and then I quickly switched the two bottles for sweet & sour and tequila, completing the task until mouths were overflowing. Customers just had to sit up and swallow.

Regulars brought friends in from far and wide for our margaritas. If they winked and tipped in advance, the newcomer would get a special upside down margarita. When they sat up their face was met with a cream pie. Actually, it was a coffee filter filled with whipped cream.

“This is the craziest bar in town,” said one smartly dressed young man to his equally decked-out friend. They ordered Heineken drafts and the first guy secretly let me know his buddy was a first-time visitor. Just as the beers were served, I pretended to accidentally knock one over. The stranger jumped to his feet to avoid ruining his clothes while his friend burst into uproarious laughter. The knocked-over glass was a fakeroo with solid contents, a means of initiating newcomers to the fun at The Jester.

The gag over, I removed the fake glass and served real beer. The instigator didn’t notice the switch. “Look, it’s a fake beer,” so saying, he grabbed the newly served glass and threw the contents into his friend’s face.

Suddenly the music stopped, the lights went up to last-call brightness, and the magic show was on. Bob and I would do a total of about ten minutes of our best stuff, the crowd would cheer, the lights would go down, the rock music cranked up, and we’d be back serving drinks. That’s how it went from late afternoon until the early morning hours night after night after night. Sometimes we locked the doors and kept going beyond the legal hours and I went home in daylight.

Customers were just as wild, raw, and often more spontaneous and ridiculous than we were. In the winter knit beanies and ski caps were popular and I had a trick where I asked to borrow one. A girl put her lacy red bra on the bar, “will this work?” and then she kindly showed everyone where it came from—her chest. The crowd cheered, and she made several new friends.

One summer we had a bowl of goldfish sitting on the back bar. Now and then, we apparently grabbed a live one outta the water, popped it in our mouth, and chewed it up. In reality, we just pretended to eat the live sushi. Actually, a secret switch was made and we ate carrots cut to an approximate goldfish shape. It was a great trick.

People started to hear about the goldfish-eating and wanted to see it done. A regular customer brought in a younger brother on holiday from college. The brother was impressed with the fish stunt, and I let him in on the carrot secret. I told him, “In the next hour we’re going to ask for volunteers. Raise your hand and I’ll put a carrot in your mouth—you’ll be a hero.” When the time came, I put a real live wiggling goldfish in his mouth.

The carrot was the bait, and the college kid was the fish that was filleted; everyone cried laughing. One night I opened the bar and the first person through the door was an attractive young girl. She asked, “Are you into yoga?” In a fraction of an instant she was on the floor going through various contortions. I excused this rather bizarre behavior as part of the phenomenon of people saying strange things and behaving even more strangely at The Jester. “Why don’t you get up on the bar so we can get a better look at what you’re doing?” She swiftly stripped down to a sheer leotard and happily knotted her legs behind her head, intertwined with mangled arms, both legs straight up on either side of her head. Thereafter she visited The Jester every couple weeks. Her many bar-top performances never failed to be crowd-pleasing events.

A number of well-known names of the time got into the spirit of the place and surprised us, including Buddy Hackett, Ted Kennedy, Cheech & Chong, Jimmy Buffet, Hunter Thompson, and Farrah Fawcett. In those days, before cell phone cameras, tabloid TV, and the Internet, Bob and I often witnessed the questionable, inappropriate, and embarrassing antics of captains of industry, movie actors, and sports stars.

The Jester environment ran the gamut from innovative magic to spontaneous outrageous comedy, an irreplaceable training ground I was privileged to be a part of. The principal thing I learned at The Jester NOT to do with my life was to be perpetually plastered, wasted, loaded, and stoned. Those days are long over for me. A quick word to my younger readers: in the long run, there are three types of people who can’t handle constant drugging, drinking, and smoking—magicians, comedians, and everybody else.

THE LEMON TRICK

Bob and I each became known at The Jester for particular feats of magic we performed individually. Those particular tricks became signature bits, because our regulars were hardy souls who seemed to have no purpose in life except to bring in newbies and request that we show them their favorite mysteries. Tourists paid the bills and locals helped promote us to them. I was best known for my rendition of The Lemon Trick. I did not originate the idea, but I did re-envision the effect— the trick as perceived by the audience, the method, the secrets and details that make the effect effective, and how the effect and method are presented.

It was back in 1969, when I was almost fifteen years old and got hired to do a show for a bunch of Cub Scouts (which put me on a search for tricks that would pack small, play big, and cost little or nothing), that I was first introduced to The Lemon Trick. It was Dai Vernon, one of my mentors you’ll be reading about later in this book, who told me about a vaudeville sleight of hand magician, Emil Jarrow, and The Lemon Trick. I started fooling with this bit back then, developing various methods and routines, but it wasn’t until I had the opportunity at The Jester to workshop the trick dozens of different ways for dozens of different audiences weekly, that it gelled into a funny, elegant hit with audiences. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Some new tricks fall into place rather quickly for me when I test them. Some are tried and discarded easily, based on audience reaction, others, like this one, can take years to simplify and routine into a thing of beauty. After Vernon described how The Lemon Trick looked, he didn’t tell me how it was done. The Professor gave hints, but no directions.

He said, “You’re a very clever boy. It’ll be good for you to figure it out. You’ll come up with something; just don’t stop thinking too soon.” It was a challenge I was happy to accept. By 1969, I’d been a student of magic for several months shy of a decade and was a fixture at the Magic Castle, a private club for magicians, for a few years. I had become absolutely obsessed with the craft and had seen each and every magician at the Magic Castle perform numerous times, literally dozens of guys. Not ONE of them did The Lemon Trick. So I never saw a properly performed example of how it might look in person.

Nor could I find it in the definitive original five-volume encyclopedic authority on magic tricks, Tarbell Course in Magic. I found the section on tricks with paper money, which included Scarne’s Bill Change, Grant’s Slow Motion Bill Transposition, LePaul’s Torn Bill, Topsy-Turvy Bill . . . but there was no sign of Jarrow’s Bill in Lemon Trick.

How could this trick be such a winner in the 1920s and it was not even mentioned anywhere in Tarbell? And out of all the dozens of great magicians at the Castle, I hadn’t seen or heard of even one guy doing it since the place opened in 1963? The reason was, at least partly, that Jarrow never published a how-to guide for his peers, and apparently never taught or authorized his invention for use by anyone; although there’s irrefutable evidence that unauthorized copycats existed in his day. How I happened to develop my particular Lemon Trick formula—and “happened” is the proper word since the evolution of the routine, like a good many in my repertoire, was not purely a matter of calculation, but a case of extensive trial and error—will require that we go back to the description of the trick Vernon gave me in 1969:

“Jarrow borrowed three bills, paper money of any denomination, which were tightly rolled together into the shape of a fat cigarette, wrapped it in a handkerchief, and the bundle was held by a volunteer. A lemon was placed under a drinking glass. Jarrow pulled the handkerchief out of the guy’s hands, and the cash was gone. The lemon was cut in half, and stuck in one of the halves were the rolled-up borrowed bills.”

The Professor went on to tell me that the trick was Jarrow’s closer; he became famous for it, and it helped make him a vaudeville star. “During the early twenties when a theater marquee advertised the then-new stage illusion, Sawing A Woman in Half, which was at the peak of its popularity, the marquee across the street, where Jarrow was appearing, advertised his act as Sawing a Lemon In Half.”

Often when magicians do a torn and restored trick with a playing card or a newspaper or a dollar bill for that matter, one torn piece is kept by a spectator, so that when the rest of the destroyed paper is magically restored, there is one piece missing, and the retained one is shown to fit in like a puzzle piece, “proving” the restored paper is the originally destroyed one. When a magician makes a playing card vanish and reappear in his pocket or an envelope or his wallet, often the card is signed by a volunteer, also as a proof, for the same identification reasons. So I asked The Professor if Jarrow used either of those methods of identification to verify in the audience’s mind that the vanished three bills were the same ones that appeared in the lemon?

He said no torn corners, no signatures, no written serial numbers, but that one identifying factor was the combination of bills borrowed was always different. One time it might be three fives, or a ten and two singles, or a twenty, a ten and a two dollar bill. The Roaring Twenties were a sustained period of economic prosperity—in addition to the currency we have today, there were also five hundred-, one thousand-, five thousand-, and even ten thousand- dollar bills in circulation.

On top of that, Vernon said that people always recognized their money. What? Of course, when I presented my teenage version of the trick as described, none of my crowd was positively convinced that the vanished bills were the same ones that appeared in the lemon. It seemed odd that wasn’t the case in Jarrow’s time . . .

Until I discovered that 1910’s American paper money was 25% bigger than 1920’s money, and 1920’s money was 25% larger than today’s currency. The bills Jarrow borrowed for the trick were up to 50% larger than today, making it an easy matter to recognize blemishes, such as, for instance, a coffee stain on a president’s face, and low-digit serial numbers on the various denominations were a quarter to a half-inch tall in the 1910s and 20s. The kind of paper money in circulation before July of 1929, when the Treasury Department began the distribution of the small bills we know today, was just plain HUGE.

Along the road to my development of an interpretation of Jarrow’s trick, I made a few key decisions. My first decision was to positively authenticate the magical transposition of just one bill. I felt that in the audience’s mind that would enhance the mystery, simplify the presentation, strengthen the effect, and negate any purpose in borrowing three bills.

As I mentioned, there could be various methods of authentication. Someone could write down the serial number of the bill before it vanished, a torn corner could be held by a helper and after the vanished money appeared in the lemon the torn corner could be matched to the bill, or someone could autograph or initial their name on the cash before it transposed from one place to another.

Yet there are inherent problems with these methods. Though the great thing about the torn corner idea is that it’s very visual, and everyone gets it as a convincer right away, the issue is that a minute later, the smart ones realize the possibility that the tiny corner could have been easily switched for one torn from a bill previously put in the lemon. The serial number idea doesn’t even have the instantaneous visual like the corner, and it’s no secret that stacks of consecutive serial numbered bills are available at any bank— erase the last digit and you have the same duplicate bill solution like the torn corner. Again, it’s too easy for the smart ones to figure out. The autograph has the instant visual of the corner, negates the idea of a switch or duplicate bill; hence, as far as I’m concerned, it is and always will be a crucial factor in maximizing this mystery.

So the decision was made to use one signed bill. The next issue to conquer was the timing. The best effect you can get with a magical transposition—that’s the category The Lemon Trick falls into—is when the time between seeing the thing in one place, and then another, is reduced to instantaneous. If a person vanishes on stage, than a fraction of an instant later appears in the audience, the effect is amazing. For the same trick, if the person disappears and ten minutes later is spotted in the crowd, it might be great, but it wouldn’t qualify as amazing.

Maybe audiences way back when were less demanding and more easily impressed—who knows? When I vanished the money from under a handkerchief, the time lapse was too long between actually seeing the borrowed money and its reappearance in the lemon. After even a few seconds, many were thinking and some even wondered out loud, “Hey, is the money still in the handkerchief or are they holding a wad of nothing?”

It was an easy task to put the cash in an envelope and burn it before it appeared in the lemon and make the sequence a laugh riot with clever comments, but as far as heightening the mystery, there was the same time lapse problem. Ideally one needed to see the autographed currency vanish and in a fraction of an instant see the very same signed-money appear in the lemon. My solution was an at-the-fingertips barehanded disappearance of the cash.

So I figured that out—they’d see the bill disappear, instantly the lemon was cut in half, and stuck in one of the halves was the tightly rolled up borrowed money. Not too bad—or so it seemed. But it was not too good either. Audiences were impressed, and all went well, except that only a few seconds after the trick, people were saying, “ . . . Was the bill really in the lemon? Is the money wet? Does the cash smell like lemon?”

Convincing proof needed to be embedded in the audience’s mind that the money was really inside the lemon. So I kept the style of vanishing the money, and its instantaneous reappearance in the lemon to create the magic moment, but I did it in a way so that spectators were certain a moment later that the bill really had appeared at the center of that juicy fruit.

Instead of the instant image of half a lemon with a rolled-up bill snatched from it, my solution, when the lemon was cut, was that only a speck of green was visible. The knife was used to dig the bill out of the lemon, selling the fact that it was really embedded in the meat of the fruit.

But there were still a number of other bits of polish to make this a winner. As a magician who stood behind a bar making drinks between doing tricks, there were a lot of distractions in our rowdy saloon that could take away your audience’s focus.

What helped to capture a crowd of eighty to ninety drinkers, and riveted their attention on a small trick with a lemon, were a few strategically placed human anchors. Instead of one volunteer loaning and signing the money, I engaged other helpers at either end as well as in the middle of the bar, widening the focus of the trick into more of a production. Vernon was the man who taught me that most magicians stop thinking about a trick too soon, and I never wanted to be lumped into that group. Here’s how the finished product looked:

A bowl of lemons sat on top of the cash register with a little sign that said “Lemon Trick.” When people wondered what that bowl of lemons with the little sign was all about, I was happy to show them if they were kind enough to loan some money.

“ . . . A twenty, fifty, or one hundred dollar bill works best. Okay! Let’s give John D. Rockefeller a big applause for coming up with the hundred bucks.” As the crowd gave John the clap, I tossed his hundred dollar bill into the tip jar and said . . . “For my next trick . . . ” everyone laughed, I retrieved the bill, “ . . . just kidding, we’ll go ahead and do the trick with this five John gave me . . . ” It really was John’s hundred, my comment was just another joke.

With a felt tip pen I drew on the money, “The first thing we do is put the glasses on Franklin so that he watches the trick as carefully as you folks do. One of the few federal offenses you’ll see here.” I pointed to a pretty girl seated in the middle of the bar, “Who are you, what’s your name? Good to meet you. Please take the pen, and on the front, the back, or if you’re really clever, on the edge of the bill, write your name. Thank you, oh isn’t that nice, she also wrote her phone number . . . and it’s an 800 number.”

I walked the length of the bar pointing out her signature, then folded the bill four times so that it became a small packet with her autograph still visible. Folding instead of rolling, so the signature was still visible, was a tiny detail that enhanced the trick start to finish, because those close to the action noticed the name both when the money disappeared and instantly when it later reappeared in the lemon, virtually impossible to arrange if the bill were rolled up.

The hundred was clipped into a doctor’s hemostatic clamp—the type that look like scissors and are commonly used by pot smokers—and handed to a man at one end of the bar. “You get to be the barbeque tongs monitor . . . actually that’s a vital surgical tool—roach clips. Hold it up high so everyone can keep an eye on the money with her name.”

The clips were a nice way to display the bill until it was needed, but I started using them because after the trick, occasionally intelligent onlookers said the bill in the lemon might have been switched by tricky fingers for the signed one upon its removal. That’s not the secret, but also not a bad guess. Using the clips to remove the bill at the trick’s finish negated that speculation.

At the other end of the bar I handed a big steak knife to a guy, “You get to be the knife monitor—you look like you might be familiar with knives. Hold it high, about even with the roach clips. I hope you like the trick. You look a lot like Charlie Manson . . . ”

Next, I returned to the center of the bar and displaying a small purple cloth bag with gold drawstrings— the type that surrounded new bottles of the Crown Royal whisky we served—reached into the bag and took out a piece of fruit. “In this ratty old bag is the mystery orange, which today is a lemon—that’s the mystery.”

After showing the lemon, it was returned to the bag, and the girl who autographed the hundred was instructed to hold the bag up high, even with the roach clips and the knife.

I looked up and down the bar at the three helpers holding the stuff, “Makes kind of a nice picture, don’t cha think? Okay, we better go ahead and do the trick. This is a very quick trick . . . it’s like a snake bite when it happens. So don’t cough or blink or look away, or you’ll miss it.”

The bill was taken from the clips. I told the guy to keep the clips handy, since they would be needed in just a second, and walked down the bar so everyone got a clear look at the girl’s signature on the hundred. I stopped in front of her and asked, “Is your name still on the bill?” If everyone couldn’t clearly hear “Yes,” I had her say it again louder. It was not only an important presentational point before the money vanished, but also a dress rehearsal for her all important “Yes” at the trick’s finish.

“Okay, everyone ready? It’s at the fingertips . . . ” I wiggled my fingers, “Yes he will, no he won’t,” and as the money vanished into thin air I said, “Now you see it, now you don’t . . . Quick, who has the lemon?” The girl screamed, “I’ve got it,” as did the man when I asked, “Who has the knife?” The lemon was cut in two, and for a fraction of an instant it looked like something went wrong and that I tried to cover it up with some jokes.

“If the trick worked . . . inside the lemon . . . uh, well . . . lemon juice . . . Does anyone have another hundred? I know I can do it . . . Wait just a second . . . Can you see it? Can you see it in there?” I pointed out a speck of green in the center of the lemon. Using the knife, the bill was excavated so it stuck halfway out. As I walked the halved lemon with the bill stuck in it over to the guy with the roach clips, I could hear a few “no ways,” “wows,” and audible gasps.

“Using the roach clips, reach inside, so everyone can see that bill come out of the fruit . . . ” As the bill emerged the rest of the way out I hollered, “It’s a boy!” I grabbed the clips holding the cash, walked them to the center of the bar, and had the girl who signed remove the money from the clips. “Unfold that bill very carefully. I’ll ask you one question—please answer in a loud clear voice, yes or no, do you see your name on that hundred-dollar bill?”

“Yes, oh yes, YES!” The crowd roared. I told her, “You were a great help, you can go ahead and keep the hundred!” Another joke. In fact, when the hundred was returned to its rightful owner, nearly every single solitary time, it was donated to the tip jar. Perhaps some of the reasons—the money was integrated into the trick, the mystery and humor had people laughing and wanting to give—but it is likely that part of the tip givers’ generosity could be attributed to the fact that no one wants to put wet sticky money in their wallet. The Lemon Trick is, intrinsically, the most perfect magic trick that anyone working for tips could ever do—past, present, or in eternity.

Near the end of the Jester years, a friend who was also a bartending magician asked that I teach him my Lemon Trick routine. Being unusually charitable about the matter, I did so, and it has subsequently been a source of profound regret that I did.

Down the road I got a call from this friend, who I had generously taught for free and who had been making behind-the-bar tips from my gift. He called to tell me that he had taught my routine on an instructional videotape that would be sold to magicians worldwide.

If he were to tell the truth, I think he would have to agree that he wasn’t exactly calling to ask for my permission since the tape had already been made. In fact, he wasn’t even offering me any compensation. Plus his call was so late in coming that it was obvious he was just attempting to soften the surprise that the video would be released the following week.

When I demanded to know what he felt gave him the right to sell my routine, his answer was “It’s a cornerstone of my bar show, I’ve been doing it a long time.” I asked, “If you sang a Beatles song in your bar show would that entitle you to sell licenses to others to sing that song?” Apparently he could not comprehend the analogy or logic or refused to understand what I was trying to say. “Don’t worry Steve, I gave you complete credit, your name is all over it, it’s advertised right on the box as Steve Spill’s Lemon Trick!” As if to prove what an ethical guy he was, he claimed, he “almost” called me the night of the filming. But he didn’t.

I felt betrayed, rooked, cheated, victimized, violated, and should have screamed at the top of my lungs, “Hey, that routine doesn’t belong to you to sell, and you know it, and you have no right to do it, cease and desist!” But I’m ashamed to say I didn’t blast him with blazing guns like I would have now.

When I hung up, something odd happened. I immediately started feeling guilty that maybe it was my own fault, mine entirely for teaching him in the first place. I started beating myself up about putting so much temptation in the man’s way and forcing him to selfishly exploit my work and gift on videotape for his own private gain. It seems to me now, in a long backward glance, absolutely crazy to have blamed myself instead of putting the blame on him where it belonged. I had been robbed.

Other pros in my circle knew the facts, but even today, in an era when music downloaders are prosecuted for theft, ASCAP collects royalty fees from stores that play background music, and emails receive automatic copyright protection, when it comes to the craft of magic, original expressions are generally not afforded copyrights, trademarks, or patents. And thus, there was nothing to be gained by driving myself crazy about this situation.

In fact, newer generations have also produced and sold nearly word-for-word, move-for-move instructional versions of my routine—some with only the very slightest of subtle variations, however trivial they may be, like different jokes, and some not even knowing they’re doing my thing.

Today, the fact remains that I have seen and heard of similar frustrating situations between magicians going as far back as my memory goes, long before I started developing my Lemon Trick routine. When it comes to resolving episodes like these, there are exceptions to every rule of course.

But in our tiny magic world, only very rarely does a confrontation, attempt at a legal remedy, or a threat of bodily harm result in anything more than aggravation of the person who has right on their side. As you might expect, it’s usually better to put your energy elsewhere, like writing about it in a book. They say that Jesus had always forgiven, even when nailed to the cross. But Jesus never developed an original routine for, or resurrected, the long dead Lemon Trick.

Spill grew up at the Magic Castle, a private club for magicians in Hollywood where his father, Sandy Spillman, was a manager in the 1960’s and the young aspiring magician was tutored by industry icons such as Dai Vernon, Charlie Miller and Francis Carlyle. Since then, he spent his entire life performing magic and producing magic shows around the globe in places such as the French Riviera’s Cannes Film Festival, Universal Studios Hollywood, Harrah’s Tahoe, and Toronto’s Massey Hall. In 1998 Spill opened Magicopolis in Santa Monica, which is the permanent home of “Escape Reality,” the show he stars in with his wife, actress Bozena Wrobel.