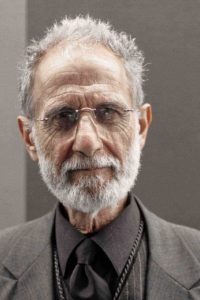

Frank Serpico’s voice reverberates through the decades

ALBUQUERQUE, NM— Former NYPD detective Frank Serpico took a bullet in the face during a Feb. 1971 raid on a suspected drug dealer’s pad in a worn-down section of the city. His two back-ups fled the scene, leaving him semi-conscious and barely alive. The cops apparently hoped he would die right there, as the suspect attempted to get away.

But an old man appeared seemingly from nowhere and cradled Serpico’s head in his hands as he spoke in Spanish, reassuringly, telling him he had called for an ambulance. That old man saved his life, and in a phone interview from his home on a farm in Upstate New York, Serpico detailed this harrowing account of his closest brush with death in his 12-year career—and the reasons behind what was likely a set-up.

Totally surrounded by crooked cops from the time he joined the NYPD in 1959, until the late 1960s, Serpico finally had enough. He was also being pressured by other cops to take money. That was something he just would not do.

He went from one boss to another, as a street cop, investigator, and an undercover narcotics officer, but they just gave him the same run-around. After being threatened with death by some of the worst cops, he finally went to The New York Times, backed up in the front-page story by a rare honest superior officer. He would later testify in court on the massive corruption within the ranks of NYPD—the only police officer from that department to ever dare such a thing.

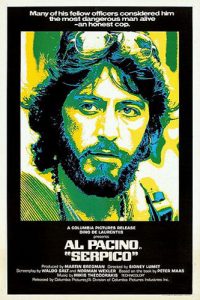

“It’s been 40 years since I left the department,” Serpico said in the recent interview. “Peter Maas did a good job (with his biography) of investigative reporting.” Al Pacino played Serpico in the 1973 film about his experiences as an idealistic cop confronting harsh and unexpected realities.

“I spent some time at (Pacino’s) house,” he said. The actor was watching the way he talked and moved, everything about him. “He asked me why I did it, why I just didn’t take the money, the pay-offs. I said to him, `what kind of a man would I be?”

From his youth, Serpico admired the cops he saw on the streets. He was the son of an immigrant cobbler—a shoemaker from Naples, Italy. His father was honest and hard-working. He taught the young boy values, as did his mother. But like all the kids, he got into a street gang and found himself in trouble one evening.

Serpico had been trying to make a “zip gun” out of random metallic parts, and a bullet and the bullet went off. He was caught by a cop who shook his head at the young boy and let him go, with the warning to stay out of trouble. He heeded that cop’s advice.

“I got a plaque a couple of years ago at a dinner, it was from the U.S. Customs and Affiliated Federal Agencies. I was walking with a couple of the officers and said `I appreciate the sentiment but let me tell you guys a story’,” he said. “Maas left this out of the book, and Sidney Lumet left if out of the movie, but when I was on vacation once—and I liked to take vacation and travel around to different countries. I was coming back through customs (at JFK Airport) and I had a bag. The Customs guy was looking at me and the bag, and he started to grab it, and I pulled out my police ID, my shield, and said, `I can save you some time.’”

The young Customs officer looked at Serpico and stepped away, getting the attention of another officer nearby.

“He said, `that guy’s a cop.’ And the other guy said, `yeah, we know.’ They told me to come with them and brought my bag to an interrogation room. I had been to Thailand and had some tea in the bag and I figured they would think it was pot or something, and they kept questioning me about it, where I’d been, and I realized they were going to flake me—that meant to plant some drugs in my bag.

A cop flakes somebody when he doesn’t find the evidence he was hoping to get, Serpico said.

“All I had been giving them during the questioning was my name, rank, and shield number,” he said. “Then they strip-searched me. They said, `you’re working for the commissioner, aren’t you?’ But how would they know whether I was nor not. Somebody dropped a dime on me.”

“I said to the officers, `I’m an American. Just a cop trying to do the right thing.’ I pleaded with them. After a while they finally let me go, but before they did one of the Customs guys said to me, `yeah, but remember one thing. If we want you, we got you’. That’s when I went to The New York Times,” Serpico said.

The Customs officers who just awarded Serpico the nice plaque had not heard that story, and they looked uncomfortable. They nodded a little and looked at each other. But Serpico was talking about a different time in America when officers just did not “rat” at all. No matter what. The corruption, it was obvious to him after being rousted at the airport, went all over—from the city to the state to the federal level.

“Before that time, I’d been told that a deputy commissioner would reach out to me,” Serpico said. “I said, yeah but what if I’m in a jam? The corruption in the city was everywhere, like an octopus with tentacles everywhere … if you’re trying to reveal something, your ass is in the bag. They don’t want the corruption revealed.”

That was the 1960s and 70s, and now the new “corruption” is not necessarily money or being on the take, but killing people for no good reason, Serpico said.

In a story for Politico, Serpico writes: “A lack of accountability is why police violence is such a problem now. I tried to be an honest cop in a force full of bribe-takers, but as I found out the hard way, police departments are useless at investigating themselves—and that’s exactly the problem facing ordinary people across the country…”

Decades after leaving his career, Serpico is still a marked man by the NYPD. It doesn’t matter that he is a recipient of the department’s Medal of Honor. But he still writes and speaks out about police corruption, and how to correct the circumstances that lead to officers justifying illegalities—and usually getting away with them.

“Police officers can pull out their weapons and fire without fear that anything will happen to them, even if they shoot someone wrongfully. All he has to say is `I believed my life was in danger,” Serpico writes. As a result, cops patrol the streets with a feeling that they can do anything.

“It still applies: power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

More than two decades ago, Congress enacted the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, requiring the Justice Department to publish annual reports on excessive force by law enforcement officers. But such reports were never published and distributed.

Serpico said every time a cop shoots someone, the police unions back that cop up immediately, regardless of what is reported. Also, district attorneys are almost always aligned with the police departments. If a DA indicts a police officer for murder, that department will attack the DA one way or another, as in the case of New Mexico’s Bernalillo County District Attorney Kari Brandenburg, who issued indictments on two Albuquerque police officers who shot and killed a homeless man in March 2014 after he was already giving himself up. His crime? Camping without a permit, and arguing with officers. The victim had six bullet holes in his back.

A New Yorker article from 2015 covered the Brandenburg, and APD, problems in detail.

In retaliation for charges filed against the two officers, later APD had undercover officers try to nail Brandenburg on a trumped-up bribery charge, which was dismissed, but still, the case was taken out of Brandenburg’s hands and handed over to a so-called independent investigator.

Brandenburg said in a local Albuquerque newspaper story she was stepping down for “fear of my life.” And was replaced with an APD-installed D.A. So, the murder charges were dropped a year or so ago—when the new D.A. stepped in. Serpico was not surprised and predicted the charges would be dropped.

“Oh no, cops never get convicted,” Serpico said.

Serpico, who once took three guns off a suspect during an arrest, armed with only a snub-nose Smith & Wesson revolver, said cops don’t need to go after crime in army tanks and combat gear—which only alienates the public, and makes the cops look cowardly.

Admiral John W. Flores is a disabled American veteran, and a journalist and author in the mountains of northern New Mexico. He is a recipient of the U.S. Navy Public Service Award—presented to him in a 2009 ceremony at the 4th Recon Battalion HQ. The citation was signed by then-Marine Corps Commandant James Conway.