Did Confederate White House host initial Civil War Thanksgiving?

The rear portico of the Confederate White House in Richmond, Virginia. (Anthony C. Hayes)

RICHMOND, VA — If American history were still taught in a meaningful way, students could engage their families around the dinner table this evening with conversation about the Thanksgiving story. Putting Pilgrim legends aside, they might note, for example, that George Washington issued a proclamation in 1789, designating November 26 of that year as a day for, “acknowledging with grateful hearts the many signal favors of Almighty God”. Or they might fast-forward 74-years to Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 proclamation, setting the last Thursday of November “as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise.”

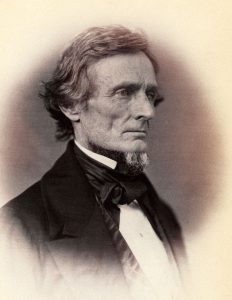

Lincoln’s edict helped affix the national holiday we celebrate today. But one curious footnote to the Thanksgiving story is that Lincoln’s proclamation was not the first by a Civil War-era leader. That distinction belongs to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

(Julian Vannerson)

“Davis was a hands-on Commander in Chief,” explained docent Chuck Young during a recent tour of the Confederate White House in Richmond, Virginia. “The dining room table was usually covered with letters and maps of the various campaigns.”

A cluttered dinner table hardly seems suited for a family meal on a special day of thanks – even if a feast wasn’t exactly what Davis had in mind.

Rather than feasting, Davis called for fasting – an idea more aligned with his Catholic faith. But to understand his motivation, the Confederate White House is a perfect place to start.

The stately mansion where the Davis family lived (it was never known as the Confederate White House during the course of the war) is now part of a multi-site entity called the American Civil War Museum. Touring the home offers invaluable insights into both Davis’ role as the Confederacy’s lone President and family life during the most turbulent time in American history.

“Davis was a West Point graduate who was all about duty and honor,” explained Young. “He was wounded in the Mexican-American War and suffered from various ailments for the rest of his life. Even though he was a former Secretary of War (under President Pierce) and a Senator from Mississippi, Davis was actually lukewarm to the idea of secession. Like Lincoln, he believed the nation did not need to be divided. But once the fighting started, he was anxious to move from prosecuting the war to prosecuting the peace.”

Young told us the house (built for a local banker in 1818) was owned by the City of Richmond in the early 1860s and leased to the Confederacy for the duration of the war.

“They (the Confederacy) were building a capital on what already existed.”

What was wartime life like for Davis and his family?

“In many ways, the nearly four years the Davis family lived in Richmond were probably the happiest of their lives.

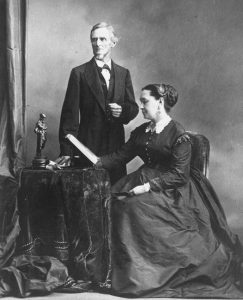

(Courtesy of The American Civil War Museum.)

“Davis was a somber 35-year-old widower when he met his engaging, younger wife, Varina. They hosted parties here at the Richmond mansion where Varina would charm Jefferson’s political opponents. He was somewhat headstrong and rather brusque. His wife was actually a better politician.

“The couple had a family of six, though only two of their children survived them. One child – Joseph – died tragically at five from a fall off the second-floor balcony. But his place was soon filled by the birth of a daughter they called “Winnie” and by an orphaned boy of mixed race named Jim, who lived with the family until the end of the war.”

Young said Davis’ tendency to micro-manage the affairs of state often led to conflict with his commanding generals. “He’d study the maps on the dining room table and issue orders long after the situation in the field had changed. He only abandoned Richmond after Robert E. Lee convinced him the fall of the city was imminent.”

The family fled Richmond on April 3, 1865. Forty hours later, Abraham Lincoln entered the elegant mansion.

“Contrary to what was reported in some of the Northern newspapers, when Lincoln visited the mansion, he did not go upstairs into the private residence and spend the night sleeping on the Davis’ bed. To Lincoln, that would have been tantamount to making an obscene gesture toward Davis, and that was not in Lincoln’s psyche.

“He did rest here for a bit by kicking off his shoes and relaxing on a chair in the parlor. Lincoln was worn out from a difficult journey and understandably tired from the long, steep walk up to the mansion from the riverside.”

What about the rumor that Davis was captured while disguised in woman’s attire?

“A lot of what was written about Davis during the war, and his subsequent escape from Richmond, was designed to discredit the man. He was eventually arrested, charged with treason, literally put into chains, and imprisoned for two years at Fortress Monroe.

“But he was never brought to trial.

“That would have been problematic for the United States government since the question of the legality of secession wasn’t settled until White v. Texas in 1869.

“How do you try someone for treason, if what they did was not against existing law? And how would Lincoln be viewed today, after prosecuting a war where 620,000 Americans died, if the Supreme Court had decided White v. Texas differently and declared the Southern states were within their Constitutional right to unilaterally secede?”

Young told us that, after the Confederacy was dissolved and Jefferson Davis was paroled from prison, the shamed family did its best to distance themselves from the crushed rebellion. For a while, they lived in Canada and Europe, as the former president looked for well-paying work. It wasn’t until the 1881 publication of his Civil War reflections that Southerners started to cotton to Davis again.

Davis died in 1889 at the age of 81. His wife Varina – who would go on to be an accomplished writer and champion of the reconciliation movement – passed away at the age of 80 in 1906. Both are buried in a family plot at the Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

Young (whose previous docent posts include the Fredericksburg Battlefield and Ford’s Theatre) said he is discouraged that public schools today have largely abandoned American History. He believes part of the problem with presenting the past is the inherent desire of people to over-simplify.

“We like to make things simple, and that is a problem with the American Civil War. The causes of the war were many and complicated. Explaining that milieu is somewhat harder here in Richmond because this was the capital of the Confederacy. A lot of the tourism here today is Civil War-driven, so there are always questions about how the mansion and various statues around town fit into an accurate representation of people and events, versus expounding the ‘Lost Cause’ narrative.”

But what about that first Civil War Thanksgiving?

That’s not a question which is normally asked on the mansion tours, though the museum may offer a solid clue into Davis’ motivation for dispatching his day of fasting and prayer proclamation.

“If you look on the wall over the dining room table, you’ll see a portrait of George Washington,” offered Young. “You’ll also see busts of Washington in other rooms in this house. Many Southerners – including Davis – looked at the Civil War as America’s Second Revolution, and Davis certainly sought guidance and inspiration in the precedents set by George Washington.”

Davis’ “Day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer” preceded Lincoln’s thanksgiving proclamation by about two years. But both men carried the weight of a warring nation on their shoulders throughout their respective terms in office. A similar fate befell Franklin Roosevelt, who signed the legislation that officially made Thanksgiving a national holiday on November 26, 1941 – just 11 days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Perhaps that’s the real history lesson for this Thanksgiving. Even in the midst of conflict – whether global or familial – our ancestors dedicated time for spiritual reflection and communal refreshment. Thankfully, one doesn’t have to do battle to understand the unifying wisdom in such actions.

Thanksgiving Proclamation, 3 October 1789

By the President of the United States of America. a Proclamation.

Whereas it is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor—and whereas both Houses of Congress have by their joint Committee requested me “to recommend to the People of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many signal favors of Almighty God especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.”

Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be—That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks—for his kind care and protection of the People of this Country previous to their becoming a Nation—for the signal and manifold mercies, and the favorable interpositions of his Providence which we experienced in the course and conclusion of the late war—for the great degree of tranquillity, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed—for the peaceable and rational manner, in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted—for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed; and the means we have of acquiring and diffusing useful knowledge; and in general for all the great and various favors which he hath been pleased to confer upon us.

and also that we may then unite in most humbly offering our prayers and supplications to the great Lord and Ruler of Nations and beseech him to pardon our national and other transgressions—to enable us all, whether in public or private stations, to perform our several and relative duties properly and punctually—to render our national government a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a Government of wise, just, and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed—to protect and guide all Sovereigns and Nations (especially such as have shewn kindness unto us) and to bless them with good government, peace, and concord—To promote the knowledge and practice of true religion and virtue, and the encrease of science among them and us—and generally to grant unto all Mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as he alone knows to be best.

Given under my hand at the City of New-York the third day of October in the year of our Lord 1789.

Go: Washington

Anthony C. Hayes is an actor, author, raconteur, rapscallion and bon vivant. A one-time newsboy for the Evening Sun and professional presence at the Washington Herald, Tony’s poetry, photography, humor, and prose have also been featured in Smile, Hon, You’re in Baltimore!, Destination Maryland, Magic Octopus Magazine, Los Angeles Post-Examiner, Voice of Baltimore, SmartCEO, Alvarez Fiction, and Tales of Blood and Roses. If you notice that his work has been purloined, please let him know. As the Good Book says, “Thou shalt not steal.”

Thank you for this article. Even decades ago my parochial school skipped thru American history. I am learning so much more now…and my heart has always been Dixie…God bless the Confederacy always