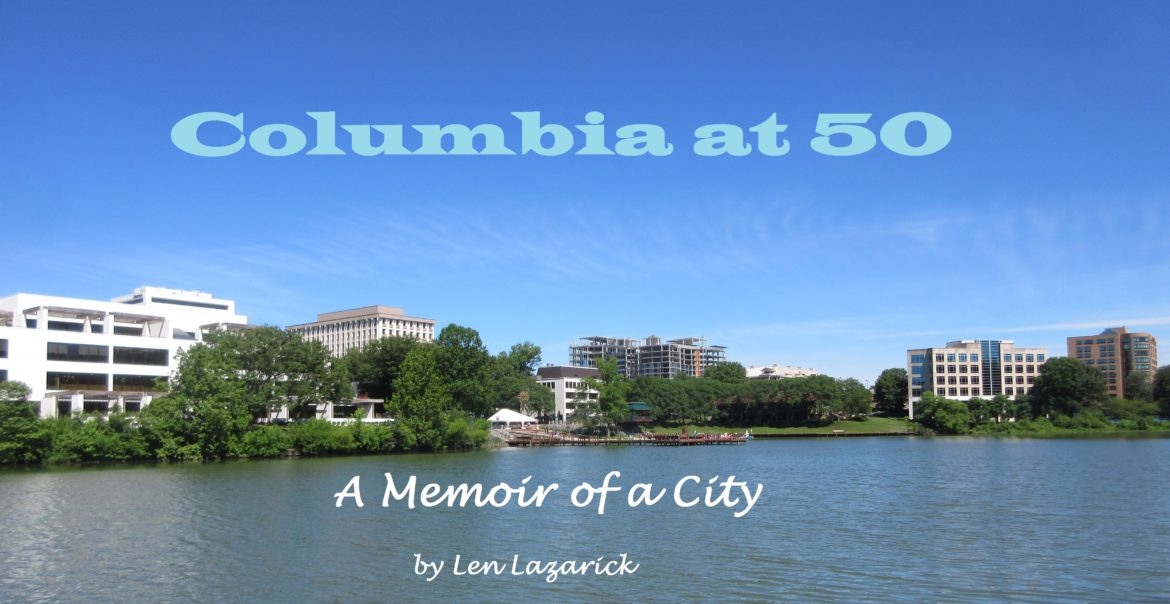

Columbia at 50 Part 9 Environment: Respecting the land while building a city

This is the ninth part in a series of 12 monthly essays leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration in June.

It ran first in The Business Monthly, circulating in Howard and Anne Arundel counties, and after that is being published here on MarylandReporter.com and by our partner website, Baltimore Post-Examiner. Read the previous articles on Columbia.

The copyright is maintained by the author and may not be republished in any form without his express written consent. Comments and corrections are welcome at the bottom.© Len Lazarick 2017

By Len Lazarick

“To respect the land” was one of the four basic goals for Columbia often repeated by developer James Rouse more than 50 years ago as he pitched his proposal “to build a complete city” on 14,000 acres of farmland, woods and stream valleys.

The goals seem almost a contradiction. If he wanted to “respect the land,” why not just leave the fields and forest as they were?

But that’s not the choice Howard County leaders and residents faced in the early 1960s as Interstates 95 and 70 were about to open — both major highways slicing through Howard County and making it easier to reach.

As Rouse explained it in 1976 — repeating arguments he had made the decade before: “Howard County, laying at the threshold of metropolitan growth pressing outward from both Baltimore and Washington, was beginning to feel the effects of unplanned, random growth. The outcropping of scattered subdivisions; ragged commercial development along major highways; increasing acquisition of farmland by land speculators … all cast their shadows across the county.”

Howard County’s population had barely grown at all since the Civil War, but it had doubled to 51,000 in 15 years by the time Columbia got underway.

If the county’s fields and woods were to be developed, as everyone expected, there was a better way to do it, Rouse insisted, one that would integrate nature into a network of neighborhoods and villages connected by pathways, many along the streams that would be forever protected.

This may seem obvious in the 21st century, but in the early 1960s, Rouse and his planners were on the cutting edge of landscape design. The planners used overlays to show stands of trees, stream beds and steep land where development would be difficult.

“It was a completely different way of thinking, especially on the scale of planning for a community of 100,000 people,” said Chick Rhodehamel, long-time vice president for open space management for Columbia Association (CA), in a 2009 interview with Barbara Kellner of the Columbia Archives. “That was monumental.”

Columbia was being laid out at the dawning of the environmental movement. Rouse said later that, when the first plans for Columbia were approved, “there was little concern about environmental issues as we now understand them.”

The Environmental Protection Agency didn’t exist; there was no national environmental policy, no Earth Day, and the Chesapeake Bay Foundation had just been formed in 1967 when Columbia’s first residents moved in. It took years for its slogan “Save the Bay” to become widely accepted in Maryland.

Surveying in Suburbia

Even as a teenager in the 1960s, I had direct experience of how traditional suburban housing developments happened. “And they’re all made out of ticky-tacky, and they all look just the same,” sang Pete Seeger in his 1963 ditty “Little Boxes.”

I grew up in Bucks County, Pa., a few miles south of the second Levittown, a huge, 1950s suburb. For four summers, from 1963 to 1966, I worked as a chain-and-rod man on a surveying crew for my godfather’s civil engineering firm.

One summer we would go out to woods or wheat fields, chopping line to clear sight-lines, and then map the topography. The next summer, we would be back to the same spot, staking out the roads and lots, marking the levels for the graders to flatten the land and perhaps take down some or all of the trees. Later we would return to put in stakes for the corners of the homes or apartments, and follow up the next year with a survey to establish where the buildings actually stood.

Much of that early surveying process still needed to occur in Columbia — a suburb or a city can’t be built without bulldozers and graders. But the main roads and side streets were designed to follow the contours of the land where possible. There would be no grid patterns of streets, but a few main drags through each village and hundreds of cul-de-sacs. The looping roads and limited connections from one village to the next that resulted is often a source of confusion and frustration for visitors — and residents as well.

The need to name all these streets without duplication in the region, as the post office insisted, and Rouse’s desire that they be named with imagination led to the many unusual street names in Columbia, subject of a 2008 book Oh, you must live in Columbia! The origins of place names in Columbia, Maryland.

It was not as if the land for Columbia was untouched wilderness. Most of Howard County had been covered with trees that were cleared after the first settlers arrived 300 years ago, and some of it had been farmed for centuries.

What was left of nature was not only to be preserved, but enhanced and made accessible, eventually with 94 miles of pathways — part of a community for “the growth of people.” The Rouse Co. required builders to protect the trees that were left on the lots, and there were rules to prevent erosion and sediment from flowing into the streams and the rivers. Erosion of the topsoil was a centuries-old problem in Maryland, initially from farming. The town of Elkridge in the county’s northeast corner had once been a deep port for sailing ships until the Patapsco River silted up in the late 18th century.

The preservation of trees was especially apparent in neighborhoods such as Swansfield, Steven’s Forest, Thunder Hill and parts of Phelps Luck. And where there weren’t trees on what had been open fields and pastures, builders, the developer and Columbia Association would plant them. The figures vary as to how many trees have been planted — in 1976, Rouse said it was “more than 350,000 trees and shrubs” — but it was certainly in the tens of thousands. There are many more trees in Columbia now than when Rouse first purchased the land, as any aerial photo shows.

The Lakes

And of course, there are lakes. They may seem like an essential element of Columbia’s natural landscape, but they are as artificial as a backyard pool.

On the Piedmont Plateau where all of Howard County sits, all lakes and ponds are man-made features. Columbia’s three lakes are dammed up streams — the dedication of the dam at Wilde Lake on June 21, 1967, is the date we observe as Columbia’s birthday. There’s nothing wild about the body of water that gave its name to what the planners initially called First Village; it is named for Frazer Wilde, the chairman of Connecticut General Life Insurance Co., which financed the new town.

Wilde Lake is the smallest lake with the hardest edges. The Cove, Columbia’s first apartments, and the distinctive white stucco of the Tidesfall townhouses, stand right at the edge of the lake, as do a series of custom homes where Jim Rouse lived and former CA President Pat Kennedy still does. Lake Kittamaqundi, with its Indian name, preceded all the office buildings in Town Center, and a few years later, Lake Elkhorn filled.

As Rhodehamel, first hired as CA’s ecologist, described it, man-made lakes are like swimming pools and “take a lot of management. … You’re fighting the forces of nature.”

Columbia lakes have several roles. Aesthetics and recreation are the most obvious. But they also have a more practical role in stormwater management and flood control. The lakes collect sediment and the nutrients that wash off all the green lawns, leading to algae blooms that suck up oxygen, killing fish and aquatic life.

As the lakes fill up, they require periodic dredging and a place to put the fertilizer-soaked soil, an annoyance to the residents who value them for natural beauty and relaxation.

Wildlife

As attractive as they are to humans, the lakes and streams also attract wildlife. Ultimately there is “more diversity than there was 50 years ago,” said environmental author Ned Tillman, who lives overlooking Lake Elkhorn. There are more species of birds and mammals than were to be found in the 1960s, like the blue herons that nab fish in the shallow lakes or the red-crested pileated woodpeckers knocking on the trees.

I often find more wildlife in my yard — a couple hundred feet from miles of wooded streambed — than I do in most parks, especially now that our dog is gone and the fence is down. The critters have little to fear and even get fed by some folks, against the strong urgings of wildlife managers.

On Christmas Day, there were eight deer in my backyard; my neighbor said he saw a dozen, far more than either of us has seen together before. The lack of two-legged and four-legged predators has led to an explosion in the deer population. I recall a conversation in the 1990s with ex-Sen. Jim Clark on his farm at Route 108 and Centennial Lane as we talked about the deer nuisance. Clark said he remembered his grandparents’ attic full of trunks covered with deer hides — which farmers thought was a good use for a deer.

The squirrels proliferate too. Former County Administrator Ned Eakle once told me that spying a squirrel in his youth in Elkridge was rare.

Two red foxes recently scurried down the sidewalk in my front yard — and because of them, there are not so many bunnies nibbling the grass. We haven’t had mice in quite a while either, which could be gratis of the foxes or the hawk that swoops around the nearby stream. We haven’t seen much of the coyote that once crossed Cradlerock Way at night.

We hosted a mama skunk and her brood of cute babies a while back under the front steps; a wildlife expert trapped them and released them far away. The dead skunk that recently stunk up the neighborhood after being squished by a car was not so lucky.

The vultures and blackbirds will sometimes roost on the rooftop. It’s hard to say which of the many berry-eating birds 30 years ago had feasted on the wild cherry tree and then perched on a nearby fence post, doing its duty, which led to the sprouting of another wild cherry tree. It’s grown into the largest tree on our quarter-acre now that the emerald ash borer has killed the towering white ash planted by Ryland more than 44 years ago.

Fortunately, we are still flyover country for the Canadian geese that park themselves on the playing fields between the East Columbia library and the Lake Elkhorn Middle School, leaving their toxic poop for young soccer and baseball players.

Alas, the swans are gone from Elkhorn and Kittamaqundi, but they were mostly Eurasians never native to the area, Rhodehamel said.

The swans may have departed Lake Elkhorn, but the beavers are still chomping away, gnawing down small trees and big bushes. One wonders if they’re related to the beavers that years ago blocked up our stream, creating their own little lake till someone at CA knocked it down.

In mid-February, I found a similar beaver dam on a stream that flows into the Middle Patuxent River. If Rouse had stuck to his original plan for Columbia, the site of that beaver dam would have been several feet underwater in the town’s fourth and largest lake that never happened.

The Middle Patuxent

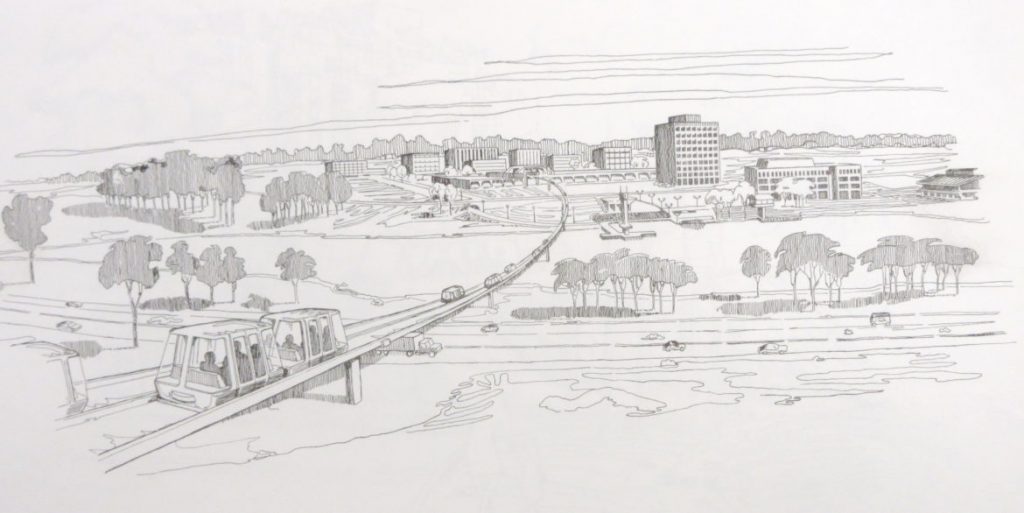

The original plan for Columbia showed Little Patuxent Parkway going straight west from the hospital. It would cross over a bridge on the Middle Patuxent River that would be dammed, creating a mile-long lake deep enough for serious water recreation, such as skiing. The road would have extended all the way through to Route 108, integrating the Village of River Hill, Columbia’s last, with the original villages and downtown Columbia.

That Columbians don’t have heavy-duty boating and water skiing can be blamed on Al Geis, a wildlife expert who lived on 20 acres near the river valley and studied bird behavior, including the mating habits of the woodcock. Geis persuaded Jim Rouse to come see the curious mating dance of the birds. It got Rouse to thinking about the whole Middle Patuxent area and the fowl and fauna that populated it. As he explained to the Howard County Zoning Board in 1976:

“We called upon the Department of Interior to examine the plan and it recommended strongly against the lake because of the destruction of plant and animal life that would result and urged instead the preservation of the stream valley.”

Antioch College, which had a branch in Columbia, did a further study, the Middle Patuxent Valley Association was formed, and in 1973, County Executive Ed Cochran asked “if there were some way the enlarged open space might be provided,” Rouse said.

The revised plan that Rouse himself was personally pitching would create 1,021 acres — 1.6 square miles — of permanent open space, 20% larger than Central Park in New York City. Columbia’s total acreage is slightly smaller in land area than Manhattan, but 25% is open space, and the population is only 6% of Manhattan’s.

County Purchases Parkland

In exchange for the developable land the company was giving up, Rouse asked the county for more density and clustering of homes on other parts of the company-owned land. The county agreed, the deal was made, and 20 years later, in 1996, the county purchased the acreage with $2.2 million from the state Open Space Program — the visionary program that passed in 1969, co-sponsored by none other than Sen. Jim Clark and his friend and fellow farmer, Senate President Bill James.

The Rouse Co. (actually it’s Howard Research and Development Corp. [HRD] division that was building Columbia and that we usually refer to it simply as Rouse) put $1.76 million aside in a trust fund for the Middle Patuxent Environmental Foundation that co-manages the property with the county’s Recreation and Parks Department.

The Middle Patuxent Environmental Area is the county’s largest park, and judging by the foot traffic, probably one of the least-known and -traveled amenities in the county. This parkland comprises largely mature, second-growth upland forest and floodplain forest. Like some of the land acquired for Columbia, its northern half had been logged and farmed as far back as the 18th century by the Charles Carroll family. Some of its “meadows” are simply abandoned farm fields, replanted with native grasses.

The Middle Patuxent is touched by housing easily visible when the leaves are gone, but is home to a wide range of wildlife. That includes “about 150 species of birds, over 40 species of mammals, and numerous amphibians, reptiles, fishes, butterflies, plants and other wildlife,” says its website.

We’ll have to take their word for it. In mid-winter, like in any northern U.S. park, there isn’t much wildlife to be seen. There are the hanging ceramic gourds for the purple martins, bluebird boxes and netting for deer that is part of a study on Lyme disease. The most common species found on its 5-1/2 miles of unpaved hiking trails is homo sapiens and their canines, leashed and unleashed.

Backyard Stormwater

Much as Rouse tried “to respect the land,” the water that flowed through it, and the trees and bushes that grew on it, there were limitations to that respect and what builders were willing to do. According to Howard County Planning Director Tom Harris in a 1974 paper, stormwater management was “designed to speed water as rapidly as possible into the streams,” not to keep much of it out of the streams as we would today.

Again, look no further than my backyard. My house is built near the top of a small slope, and six other lots send the rain that doesn’t soak into the ground through slight gullies and then through my yard into a drain at the far back corner.

When that rain comes in torrents, the flow is like a river that can’t be stopped. With the push to reduce polluted stormwater runoff that contains fertilizer, soil, oil and other unwanted chemicals, the county and CA have new programs to manage the runoff. For my yard, only a massive rain garden with rocks would do, unless my “upstream” neighbors put in their own rain gardens to prevent a problem they never see.

Cars and Transit

An influx of 100,000 people, even with the most enlightened environmental management, creates massive amounts of impervious surfaces where people live, work, shop, play and park their cars. The automobile made Columbia possible, but it is one of its principal environmental villains.

Cars and trucks need impervious asphalt and concrete to drive and park on, and the county probably required wider streets than were necessary. Oil on the roads eventually flows into the storm sewers and into the streams; carbon and heat spew into the air, expanding the heat island that Columbia has become.

The noise from traffic intrudes on the most bucolic of scenes, like the path along the meandering Little Patuxent River and its wide flood plain southwest of Lake Elkhorn. The roar of Route 32 can be heard at great distance, though not as loud as the roar of I-95 high above on concrete stilts further downstream. About the only birds to be heard in mid-winter from the Middle Patuxent Valley are soaring jets making their ascent from BWI.

The early planners had every hope of getting people out of their cars and off the streets, not just walking and biking the paths (running for exercise was barely in its infancy), but to use transit services. Many staff-years went into designing dedicated bus routes, and even contemplating small people movers. State and federal transportation officials were lobbied and cajoled.

In 1964, there was talk of “tiny buses every five or ten minutes,” no more than a three-minute walk from every residence. There was even an outlandish estimate of a daily ridership of 29,000.

The reality was much more modest when Columbia residents arrived. In 1969, Robert Bartolo, the Rouse Co.’s transportation planner, reported that “nearly every resident in Columbia had experienced or heard a ‘horror story’ concerning Columbia transit.”

There were tales of stranded passengers, lost drivers and missing buses. Call-a-ride was more successful, but mass transit in Columbia has hobbled along from the start, much as it does today. Ridership declines, fare box revenues go down, and schedules are reduced in a vicious cycle. Only people who can’t afford a car are desperate enough to take one of the half-empty buses and get to their destination a few miles away two hours later.

Columbia Association operated the bus system for 29 years, struggling with limited resources. In 1996, it finally persuaded Howard County government to take over the bus routes.

“It takes density to do transit,” said Marsha McLaughlin, former director of planning and zoning for 13 years. “But Howard County is very lucky from a road and transportation point of view. … We have a phenomenal state road network.”

Roads and Highways

As much as Rouse officials worked on transit solutions for the new town, they paid even more attention to improving highway access. Old-timers like myself can recall the original traffic lights on Route 29 to get across town from Oakland Mills Road, Owen Brown Road and Route 108.

Rouse executives worked for years with state highway officials to expand lanes, build interchanges, improve signage and move traffic in and out of Columbia. Highway planning and construction often takes decades.

Jim Rouse, a major player in civic and business organizations, would contact high state officials directly. In one interesting exchange in December 1966, Gov.-Elect Spiro T. Agnew thanked Rouse for his recommendation of a person to head what was then called the State Roads Commission. Agnew signed his letter “Ted,” and shortly afterward, he appointed Jerome Wolff, a Towson transportation consultant who worked for Rouse and others Agnew knew as Baltimore County executive, as head of the Roads Commission.

HRD officials strongly lobbied for expansion of Routes 29, 32 and 175 the way they wanted them, and even funded interchanges in advance to improve traffic flow. Sometimes they prevailed; other times they didn’t. While the two-lane Route 29 is now a six-lane walled expressway, the traffic it carries is often just passing through Columbia, adding to the air, noise, water and heat pollution. On the other hand, without Columbia’s planned shopping centers, Route 29 was destined to become crowded with the same kind of piecemeal strip development that lines Route 40 in Ellicott City.

What was much less successful were attempts to improve mass transit into and out of Columbia. An extension of the Baltimore light rail line that appears on some plans never materialized. Regional transit agencies have provided workforce transit to places such as BWI and Arundel Mills; and commuter buses into D.C. and Baltimore are often crowded, but operate only on weekdays and limited schedules. Residents are mostly dependent on cars to get to them. There is a study of bus rapid transit down Route 29 to Silver Spring, but the four-lane bridge over the Patuxent River reservoir would be a major bottleneck.

The density of Columbia’s downtown development is supposed to provide more transit options, if only in Town Center.

While people pay attention to the streams and rivers that flow above ground, only public works officials and civil engineers pay much attention to the underground supply of water that people use to drink, bathe and flush. It comes from reservoirs far away in Baltimore County; the waste water departs underground largely along stream beds downhill to the sewage treatment plant in Savage. Some of that treated wastewater is now used to cool huge computers at the National Security Agency, where many Columbians work.

Judging the Environment

Environmental expert Ned Tillman has been watching Columbia for decades, first from a small farm on Manor Lane just outside the town, and now perched in a condo with a grand view of Lake Elkhorn though the trees.

“Open space is probably one of the major successes of Columbia,” Tillman said in an interview. “Many cities and towns did not do a good job of that.”

“We have to learn to co-evolve with nature and make sure that the green infrastructure here is healthy,” he said. “Howard County needs biodiversity.”

Tillman has written about the big picture in his books The Chesapeake Watershed and Saving the Places We Love. He advocates government action and corporate leadership, as the Rouse Co. showed, but he urges individual efforts as well.

Under the Trump administration, “one could expect the air quality is going to get worse. It’s all about the overuse and use of fossil fuels,” Tillman said. Much of the local air pollution comes from the heavy traffic on I-95 and coal-powered electricity plants to the west, where a lot of our local power originates.

“I’ve been supportive of downtown redevelopment, because it is going to help fix some of the stormwater runoff problems in downtown,” Tillman said. “I was glad to see Howard Hughes [Corp.] work on the Little Patuxent River streambed, which was revitalized, and how stormwater bio-filtration systems were added to the Whole Foods parking lot.”

On the stormwater issues that plague many neighborhoods like my own, “The developers could have done a better job,” he said, but homeowners can take action on their own. “Everybody has yet to re-landscape their backyards,” though people are planting more native species.

The state planning department estimates Howard County’s population will grow by 50,000 people over the next 20 years, and perhaps 10,000 of them will be residents of new downtown apartments. “Our green infrastructure is going to be under stress,” said Tillman.

But he noted that, while the population of the mid-Atlantic states has doubled since 1960, Howard County’s has grown seven-fold. “It’s incredible that we have any nature left.”

But, as many Columbians could attest, nature is just outside the door or a short walk away, as Rouse planned it 50 years ago.

Next month: The Arts and Entertainment

MarylandReporter.com is a daily news website produced by journalists committed to making state government as open, transparent, accountable and responsive as possible – in deed, not just in promise. We believe the people who pay for this government are entitled to have their money spent in an efficient and effective way, and that they are entitled to keep as much of their hard-earned dollars as they possibly can.