Bridge of Spies: Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks heat up the Cold War

3 out of 4 stars

The numbers speak for themselves: three films, and over $1 billion at the box office off a budget of $182 million.

When director Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks get together, their movies crank out more cash than the mint.

In 1998, Saving Private Ryan grossed more than $481 million worldwide off a $70 million budget, and four years later, Catch Me If You Can hauled in more than $352 million – $300 million more than its budget. In 2004, Spielberg had Hanks wonder around an airport, called it The Terminal, and then watched his $60 million film bring home more than $219 million.

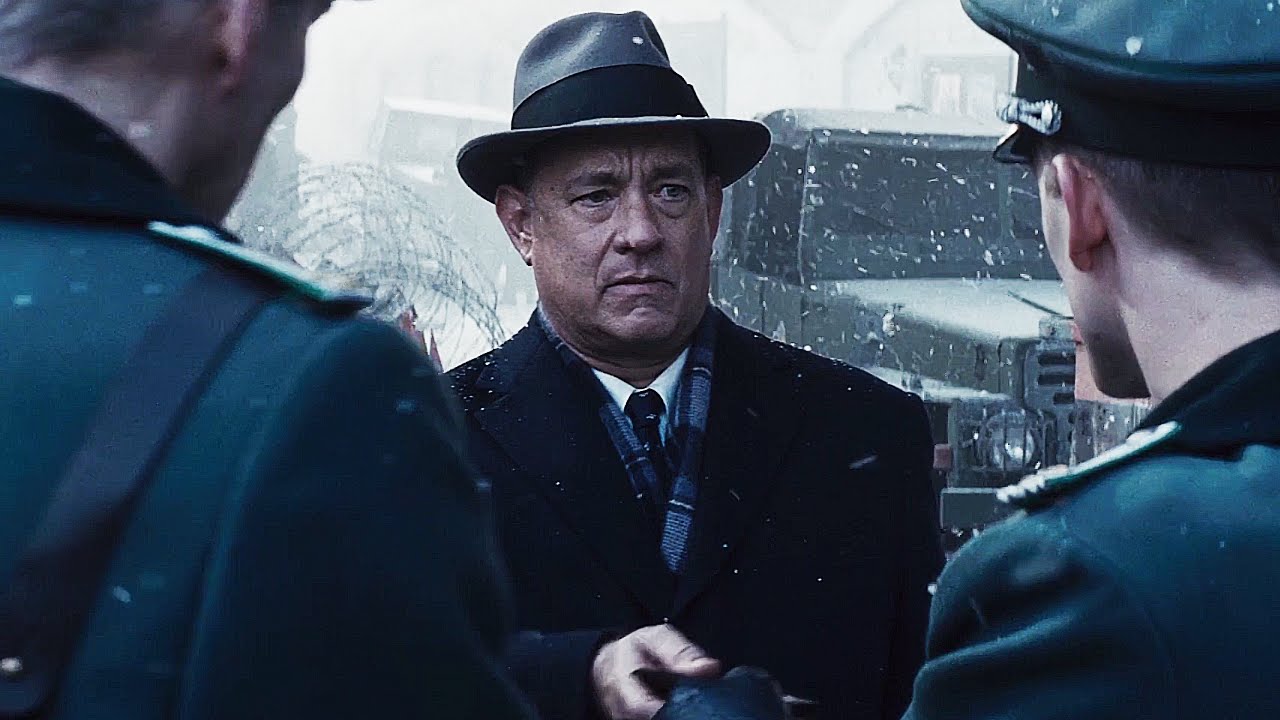

Which leads us to today, when the best director of his generation – and maybe ever – teams with arguably the best actor of his generation to tell the tale of the most famous prisoner exchange between U.S. and Soviet Forces in Bridge of Spies.

Oscar nominations are still four months away, but expect Bridge of Spies to be nominated for Best Picture.

It’s going to happen, so don’t argue: each of Spielberg’s last three dramas – Lincoln (2012), War Horse (2011) and Munich (2005) – all made the cut, though none won.

And that doesn’t mean Bridge of Spies will earn Spielberg just his second win in category (Schindler’s List in 1994), because the film is more like a really good history lesson than a cinematic masterpiece.

Bridge of Spies’ first hour so focuses on the capture and trial of Russian spy Rudolph Abel (Mark Rylance) and his Brooklyn insurance lawyer assigned to his case – James B. Donovan (Tom Hanks), who wouldn’t be more patriotic unless he wore an Uncle Sam hat in the courtroom.

It’s 1957, the height of the Cold War and paranoia is running high. Americans hate Russians and aren’t too fond of one of their own defending a Communist who has already been convicted in the court of public opinion.

“As a child of the 1960s – I call myself a Sputnik kid – I was very much aware of what the stakes were,” Spielberg recently told The Miami Herald. “In junior high, we were shown films about what to do if you saw a big white flash in the sky and how you had to duck and cover. This was part of my life: Watching Sputnik fly over my neighborhood at night, thinking it was a spy satellite that was listening to every word we were saying right through the roof of our house.”

While Abel is being cast as Russia’s threat to everything Americans hold dear, U.S. Air Force pilot Francis Gary Powers is shot down and captured while in Soviet airspace, meaning each country has somebody the other nation wants returned.

It’s time to deal: a spy for a spy, which is the focal point the second half of the 141-minute film. But Donovan wants the Russians to throw in another American they captured, even though the college student doesn’t have nearly the amount of classified information than Powers.

So the planet’s biggest bullies – Americans and Soviets – decide to meet on a bridge in Germany to swap prisoners, with – you guessed it – Donovan handling the negotiations for the good ol’ U.S. of A.

Hanks, a two-time Oscar winner, delivers yet another fine performance, but he doesn’t outshine Rylance, the two-time Olivier Award and three-time Tony Award winner who makes the audience compassionate about a spy it’s supposed to loathe.

How much of the dialogue and scenes in Bridge of Spies adhered to what really happened? We’ll never know – that classified information is probably buried alongside what really happened that day in Dallas when President Kennedy was shot.

“I never wanted to present Bridge of Spies as a movie in which every single moment is true,” Spielberg said. “In order to preserve a sense of drama and suspense and make a spy thriller, we invented things that never happened. But all the big nuts and bolts of the superstructure of the story did occur.”

But is Bridge of Spies believable? Absolutely. Spielberg’s exquisite eye for the meticulous details revealed through conversations, courtroom proceedings, military protocols and American paranoia heat up the tension of the Cold War.

“Bridge of Spies is about the art of the conversation,” Spielberg said. “In the Cold War, when words could be interpreted as lethal weapons, there was a great deal of danger in what was said and even more danger in the things that went unsaid. The saber that was always rattling was nuclear Armageddon.”

Jon Gallo is an award-winning journalist and editor with 19 years of experience, including stints as a staff writer at The Washington Post and sports editor at The Baltimore Examiner. He also believes the government should declare federal holidays in honor of the following: the Round of 64 of the NCAA men’s basketball tournament; the Friday of the Sweet 16; the Monday after the Super Bowl; and of course, the day after the release of the latest Madden NFL video game.