Three bills seek to overhaul legislative redistricting process

By Margaret Sessa-Hawkins

Maryland’s controversial legislative redistricting is again the target of bills designed to overhaul the process and make it less partisan.

Maryland’s controversial legislative redistricting is again the target of bills designed to overhaul the process and make it less partisan.

Though very different in their scope and design, the bills have one thing in common: They are trying to introduce transparency and civic participation into the redistricting procedure, which now leaves the governor in control and the process wide open to political gerrymandering.

“Gerrymandering has been going on for a long time,” said Carol Ann Hecht, of the National Council of Jewish Women Annapolis Section. “Both parties do it, and it’s wrong. The citizens in this state know that the system is broken, and they don’t know what to do.”

Under the current legislative redistricting system, the governor introduces a legislative districting plan to the General Assembly as a joint resolution two years after a census is conducted. The General Assembly then either approves the plan, or devises its own joint resolution. If no alternate resolution is agreed upon by the 45th day, the governor’s plan goes into effect.

Maryland governor controls process

“There are quite a few models nationwide in different states of better ways to do the process,” Jennifer Bevan-Dangle of Maryland Common Cause said. “Maryland has one of the most governor-controlled processes out there.”

Two of the bills, introduced by Democratic Sen. Delores Kelley of Baltimore County and Sen. Allan Kittleman, R-Carroll-Howard, call for amendments to the Maryland constitution.

Under Kelley’s bill, SB414, the districting plan would be presented to the General Assembly as a bill rather than a joint resolution, and would be guaranteed hearings.

Kittleman’s bill, SB740, calls for the appointment of a bipartisan seven-member legislative districting commission that includes no elected or party officials.

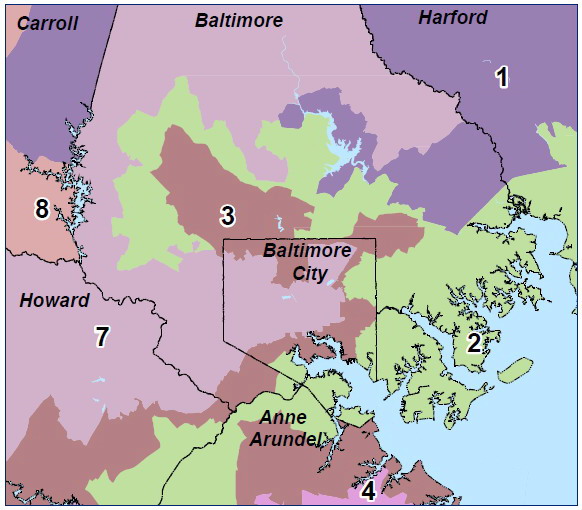

The third bill, SB582, sponsored by Sen. Norman Stone, a Baltimore County Democrat who won a lawsuit against Gov. Parris Glendening’s 2002 redistricting plan, would require that, with any redistricting measure being voted on, links to online maps be provided, and maps also be displayed at polling places.

In 2012 a Republican-led petition placed the new congressional district maps on the ballot for voter approval. Voters did approve them, but opponents felt the issue was not adequately understood. In that instance, maps were not included in the information given to voters.

Public is uninformed

“With regard to legislative redistricting, the public never really knows what the actual plan is until it’s too late to do anything about it.” Kelley said. “It’s kind of a legal fiction that there’s real civic participation regarding the outcome and the construction of the actual plan.”

This is not the first time the state’s redistricting procedure has been under scrutiny, or even legislative pressure. In mid-2012 Kelley and Sen. James Brochin, D-Baltimore County, a co-sponsor of Kelley’s bill, sued to have the current redistricting plan invalidated.

“I’m finding out that most of my constituents are just finding out that there’s been redistricting because there’s an election,” Kelley said. “People are not aware. They don’t know why they got a new voter’s card and it’s got a new number on it in some cases.”

The senators are hoping that their bills will go some way towards ensuring that in the future, in 2022 when districting maps are redrawn again, voters will not only know about it, but will have a more active role in the process.

Attempts to reform the process last year never made it out of committee after hearings.

MarylandReporter.com is a daily news website produced by journalists committed to making state government as open, transparent, accountable and responsive as possible – in deed, not just in promise. We believe the people who pay for this government are entitled to have their money spent in an efficient and effective way, and that they are entitled to keep as much of their hard-earned dollars as they possibly can.