‘Made in Bangladesh’ garment exports generate profits, but breed misery at home

This is the first in a three-article series on labor conditions in Bangladesh by Larry Luxner, a freelance journalist based in the Washington, D.C., area. Luxner spent 11 days in Bangladesh earlier this year as a guest of the country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. To read the entire series click here.

CHITTAGONG, Bangladesh — Late last month, 111 factory workers burned to death in a fire at Tazreen Fashions, a nine-story garment plant on the outskirts of Dhaka. The Nov. 24 tragedy — since ruled a case of arson — briefly made Bangladesh prime-time news and enraged human rights groups that have long called this overcrowded South Asian country the world’s biggest sweatshop.

Yet talking to Suvashish Bose, vice-chairman of the government-run Export Promotion Bureau, you’d almost think you were in Switzerland.

“People are satisfied with what they have,” he said. “Bangladesh has about 5,000 garment factories employing about 3.6 million workers, 80 percent of them women. They are submissive, adaptable and trainable. They can understand everything very quickly, and these workers are abundantly available wherever you want to set up your factory.”

Pressed for an explanation, Bose proudly said that “a few years ago, Bangladesh was ranked the happiest country in the world, according to a survey conducted by the London School of Economics. Now Bhutan is the happiest, and Bangladesh is the second-happiest. It’s because the demand for basic necessities is very low.”

Oh yes. During a trip to the Chittagong Export Processing Zone earlier this year, this reporter tried to mingle with hundreds of such “happy” workers, but was prevented from doing so. The massive industrial park — home to hundreds of factories churning out products for Nike, Reebok, JC Penney, Gap, Walmart, Kmart, Wrangler and Tommy Hilfiger — is located on the outskirts of Chittagong, a teeming port city whose four million inhabitants make it the second-largest metropolis in Bangladesh after Dhaka.

Our 12-member press delegation, invited by the country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to publicize economic development in Bangladesh, included print journalists from the United States, South Korea, Japan, Great Britain and Belgium, and TV crews from as far away as Kenya, Greece and Uzbekistan.

We were warmly welcomed by S.M. Abdur Rashid, general manager of the Chittagong EPZ. He showed a 15-minute promotional video from the Bangladesh Export Processing Authority, and followed that with a briefing about the EPZ itself.

“This zone was inspired by Robert McNamara, president of the World Bank,” he said proudly, pointing to a map of Bangladesh. “Accordingly, our government passed an act in 1980 to strengthen the country’s economic base by promoting investment and generating employment. There are now export processing zones in Karnaphuli, Chittagong, Comilla, Adamjee, Dhaka, Mongla, Ishwardi and Uttara.”

The zones together employ 324,000 Bangladeshis — 64 percent of them women — and Chittagong’s EPZ is by far the biggest. Rashid said 225 of the factories here are foreign-owned (from 37 countries), while another 63 are joint ventures and the remaining 113 are purely local investments.

In 2011, the Chittagong EPZ generated $2.35 billion in export revenue for Bangladesh, with most of its finished products going to its chief market, the United States. All told, Bangladesh racked up $23 billion in exports that year. Apparel, which includes woven garments, knit garments and home textiles such as curtains, towels, linens and pillowcases, accounted for 78 percent of the total.

“Thanks to reforms introduced in the 1980s, foreign investors can now invest any amount of capital and retain 100 percent equity ownership,” he said. “Restrictions on the movement of foreign capital have been abolished. The law also guarantees against nationalization or expropriation of their assets.”

One more thing prospective investors considering Bangladesh can count on: no pesky trade unions to make trouble.

That’s helped make this country the world’s second leading exporter of apparel after China — though it’s also infuriated American groups like the AFL-CIO, which is now trying to get the Obama administration to revoke trade preferences for Bangladesh.

When it came time for questions, we asked Rashid why the Chittagong EPZ expressly forbids the establishment of unions — a situation that would be illegal in most other countries. The free-zone boss looked genuinely puzzled.

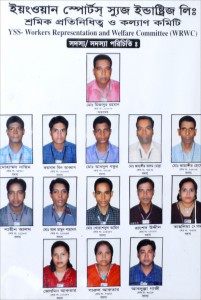

“We allow Workers Welfare Associations. It’s collective bargaining,” he said. “The workers enjoy it and they’re happy with the WWA. Unions might be affiliated with political parties, and we do not want our workers to be affiliated with political parties.”

Of course they don’t. Unions that had any real teeth might demand better salaries for their rank-and-file members than the $48 average free-zone wage now in effect. At $1.50 a day, that means Bangladeshis are the lowest-paid workers on Earth.

On the other hand, said Rashid, it also makes Bangladesh more competitive than any of its Asian competitors: Pakistan (with average factory wages of $80 a month); Vietnam ($84); India ($109), Malaysia ($132), Indonesia ($135) and China ($250).

After the briefing, EPZ officials took us on a highly orchestrated tour of the Youngone footwear plant, one of 11 the Korean conglomerate operates in Chittagong.

The plant manager, identified only as Mr. Shahin, said 85 percent of the 3,500 workers in this particular factory are women. They make 14,000 pairs of shoes a day — or more than five million a year — on contract for Nike, North Face, Timberland and L.L. Bean, among other buyers.

“We pay higher than normal minimum wages. That’s why our turnover rate is so low, only 2 percent per month” said Shahin. “People are very happy here.”

Yet a stubborn female supervisor tried to discourage us from photographing the workers — even going so far as to physically position herself between our cameras and the factory floor. We were also ordered not to take pictures of crates or boxes that would identify U.S. customers, though many in our group secretly did just that.

What exactly were these factory bosses trying to hide?

Earlier this week, a high-level investigation concluded that the Nov. 24 disaster at Tazreen Fashions — one of the worst fires in the history of Bangladesh — was a case of sabotage; supervisors apparently told the women working at their sewing machines that the whole thing was a drill and padlocked the exits to prevent anyone from escaping.

But even before the horrific blaze, activists at home and abroad had accused for years accused Bangladesh’s apparel export industry of paying its workers slave wages while maximizing profits at all costs — accusations local officials here dismissed as preposterous.

“Some people are trying to create unrest in Bangladesh in order to take advantage,” claimed Bose, the export promotion chief. “Maybe they are competitors. If we allow unions, there might be strikes or other unrest, and foreign investors will have problems. Productivity will decrease, and we do not want productivity to decrease.”

Not one official during our visit to Chittagong mentioned the fact that in December 2010, thousands of workers attacked factories in a dispute over poor wages and working conditions. Police responded with live bullets and tear gas; three people were killed in the riots, which led Youngone to temporarily close all its factories.

It was those demonstrations, in fact, which forced Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to raise the minimum wage to its current $37 a month, not including overtime and bonuses; it had been only $21 a month prior to the protests.

Jef Van Hecken, a Belgian adviser to the Dhaka-based National Federation of Garment Workers, said any worker who tries to organize a union is dismissed.

“There’s real harassment and death threats,” he said, pointing to the April 4 disappearance of labor organizer Aminul Islam. His body was later discovered, with signs he had been tortured, yet nearly nine months after his murder, no arrests have been made.

Shamarukh Mohiuddin, executive director of the Washington-based U.S. Bangladesh Advisory Council, said that as long as there’s a pool of workers willing to labor for dirt-poor wages, employers don’t have much of an incentive to change course.

“Many employers refuse to increase wages, or to invest in labor productivity, citing the uncertainty of maintaining their relationships with foreign retailers,” she said. “We have seen this in China where a rise in worker wages has led orders to shift to cheaper destinations, including Bangladesh, so there is a very real fear on the part of employers that other poor countries may undercut them.”

In 2010, Bangladesh raised the minimum wage by 87 percent, said Mohiuddin, but it still remains a “least developed country” with about 70 million of its 158 million inhabitants living below the poverty line.

“In terms of higher wages, the pressure needs to come from Western customers through the retail brands,” she said. “The fact remains that apparel jobs are still some of the most coveted jobs for the poor, since they pay much higher wages relative to similar, labor-intensive low-medium skill jobs and, in fact, offer better working conditions.”

During an interview in Dhaka, the country’s foreign minister, Dr. Dipu Moni, tried to put the issue into perspective.

“Bangladesh is a poor country and there are large number of people who still live under the poverty line. People here work really hard, and the garment industry’s wages are low, but it sustains them,” she said. “If our product becomes less competitive, then they don’t make money at all. So in order to remain competitive, industries keep their wages low. If we didn’t have these jobs, where would those three million women work?”

Larry Luxner is a freelance writer with The Washington Diplomat and former editor of CubaNews. Born and raised in Miami and now based in Israel, Larry has reported from every country in the Western Hemisphere. His specialty is Latin America and the Middle East, and he’s written more than 2,000 articles for publications ranging from National Journal to Saudi Aramco World. Larry also runs an Internet-based stock photo agency at www.luxner.com.

baby garments export left over

Very well-written series that shed a necessary light on these deplorable conditions. If more people speak up, maybe something will change for these poor people.

Great article that provides a very good picture of the nuances of the issue.

I enjoyed these articles. Is like reading fiction about the horrors of savage capitalism, and Bangladesh a paradise for exploiters, traitors and mysogynists. Thank you for such well written stories and brave reporting. My heart goes out to all the people having to work for such greedy companies who think humans beings are ‘adaptable’, ‘trainable’ and happy making meager wages.

Luxner did a great reporting job on this story. I cannot wait to see the next installment. It’s one thing to read an AP story that’s probably been cut and sanitized, and another to actually have a canny reporter on the ground.

So Nice Article about Bangladesh. Like it & Thnx a lot for ur Positive Viev abt Bangladesh.

Nice article. As i wear my Indonesian sewn shorts.