Ferguson Reid’s movement can bring change to Virginia

It’s the cusp of his 90th birthday, but civil rights icon Ferguson Reid is still gearing up for the long haul.

“We have the races in 2015, 2017, and 2019 to get the majority,” he tells me, referring to the off-year elections for control of Virginia’s state government. “And this election will determine whether or not we’re able to get a House majority for 2021.”

The Democratic political veteran seems happy and relaxed in our conversation, even as he acknowledges the challenges his party faces in Virginia. He shows an encyclopedic knowledge of his state’s history and its current crop of candidates, sounding upbeat about Democratic chances this fall despite the steep hill they need to climb in one chamber. Republicans rule the roost in the state House, where they’ve set up a firewall against Democratic Governor Terry McAuliffe’s priorities. And thanks to a computer-drawn map that’s gerrymandered the Old Dominion to within an inch of her life, the Governor’s naysayers seem secure in their power – at least for now.

“Hopefully we can find someone to run in every House seat,” Reid says. “That would increase the chance of winning.”

If a month really is a lifetime in politics, it might seem incomprehensible to lay the groundwork for the 2019 election years in advance. But Fergie Reid is used to playing a long game.

He began fighting for political change in Virginia in the 1950s, becoming a voice for civil rights and integration at a time when the Democratic Party was in a state of flux. The party was torn between its segregationist roots and liberals who believed in FDR’s progressive vision rather than the ancestrally Democratic former Confederacy.

So Fergie Reid, already a medical doctor and community leader at the age of 30, formed an organization with some other progressives. The Crusade for Voters was founded in 1955, and it became one of the most important political operations to bring change to Virginia. It lobbied for the registration of black voters. It led get-out-the-vote drives. And as it grew in strength as measured by volunteers, resources, and reputation, the Crusade for Voters became formidable enough to help Reid make history.

In 1967, he became the first African American elected to Virginia’s General Assembly in the 20th century. It was a momentous occasion – but there were no longer as many Democrats in Richmond to welcome him as there might have been just a few years before.

“When I got there,” he remembers, “the Byrd machine was dying out, and because of that, a lot of Democrats in the legislature switched over to the GOP.”

Harry Byrd was the segregationist Democratic Governor who had died only the year before, in 1966. An avowed white supremacist, he had ruled Virginia officially and unofficially for the last forty years, holding the office of Governor and then Senator as his political machine dominated the state’s politics. He had organized “massive resistance” to defy the Supreme Court’s integration orders, and his cronies in the legislature drafted laws to make it harder for blacks to enroll in schools. Byrd’s closing of schools to prevent them from being integrated created a “lost generation” of African Americans in Virginia, as tens of thousands of blacks were denied any chance at an education for years.

Harry Byrd and his followers in the segregationists’ hey-day were Democrats for the same reason their fathers and grandfathers had been. They had historically had no use for the party of Lincoln, which smashed the Confederacy and destroyed an old way of life. But as the civil rights movement gained strength and won a platform in the modern Democratic Party, segregationist Democrats bolted the party in protest. It was a dramatic enough flight for President Johnson to muse that as he signed the Civil Rights Act into law, he was also signing the South away to Republicans for at least a generation.

Ferguson Reid embodied the change that the Democratic Party underwent in the 1960s and beyond. With some allies in the legislature, he took a hammer to the segregationist policies that had set him back years in his education and career, and cost thousands of others far more still.

As a first-term lawmaker who had yet to accrue seniority and clout, a lot of his motions for equality were symbolic at first. He had noticed that the Assembly had no black pages interning in Richmond. So he urged the Henrico delegation to appoint a black page, and won out in his push.

Reid had also noticed that there were no female pages, so his next initiative was to appoint a female page to participate in the state government. He won again.

Then he became chairman of the Labor Committee, and fought for enforcement of the Open Housing bill that would attack the state’s lingering segregationist tendencies at the roots. Won.

Looking back on his experience, he remembers his colleagues in the Assembly warmly. I asked him if there were any jarring instances of racial tension, thinking of Jesse Helms, the U.S. Senator who took pleasure in whistling Dixie when in the company of Carol Mosley Braun, the only black Senator in the chamber at the time. But Reid told me he endured nothing like that.

“People were civil,” he said, even civil rights opponents. Civility was part of being a “Virginia gentleman” and it was practiced at least face-to-face in the chamber by liberals and conservatives alike.

But there was one instance at the Commonwealth Club, a place where most social functions in the state government were sponsored. A prominent member who traditionally invited every member of the General Assembly to his annual dinner did not invite Reid. When they heard of the slight, several of the more liberal Democrats boycotted the dinner in protest.

That sort of exclusion would become rarer in Democratic politics over the next decade, as thousands of grateful black voters, newly enfranchised by the Civil Rights act, rewarded the party of LBJ at the polls and in the process pushed the party to the left. And as this dynamic played out, black leaders ascended to office and followed in Fergie Reid’s footsteps. In 1973, Hermanze Fauntleroy became Virginia’s first black mayor ever. Roanoke and Fredericksburg also elected black mayors just three years later. In 1977, most of Richmond’s city council members were black, something that would have been unthinkable a decade ago. And by 1985, there were seven black members in the General Assembly, where Fergie Reid had been the first one in 82 years in 1967.

Throw Governor Wilder’s 1989 election win to become the first black governor in southern history and Barack Obama’s two statewide wins in Virginia into the mix, and it’s clear that Harry Byrd would no longer recognize his former political playground. But for every victory, there are also new challenges.

I asked Reid about the voter ID laws in the state and the Assembly’s resistance to expanding absentee voting. He was quiet for a moment before replying.

“These people never give up,” he said. “And they never want to be defeated.” While musing about the flurry of voter ID bills circulating in Richmond, he mentioned Virginia’s state convention in 1902, pointing out that the resulting poll taxes had one not-so-secret purpose.

Someone on the floor had asked Carter Glass, the leading Democrat at the convention, whether the poll taxes he had just enshrined into law would have the effect of stopping blacks and poor people from voting. Glass gave a forthright reply.

“Discrimination! Why, that is exactly what we propose. To get rid of every negro who can be gotten rid of legally, without materially impairing the numerical strength of the white vote.”

After the poll taxes were enacted, the number of eligible black voters would drop from over 150,000 to under 10,000 by 1930 — just as Glass envisioned.

The 90 for 90 Project

“Voting is a great equalizer,” Fergie tells me, “because believe it or not, on Election Day our votes count as much as the Koch brothers’!”

There’s some joy in his voice as he observes the fact. And despite all of the decades he’s had to dwell on this truth, there’s wonder, too. He’ll never take this right for granted, he says, because freedom is not free, and neither is it eternal. What one Amendment allows, another can undo.

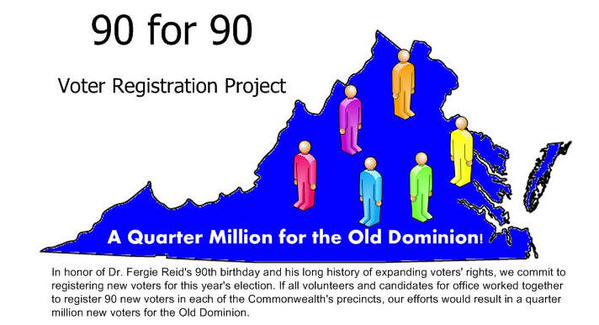

Activists in Virginia aren’t taking it for granted either. In honor of Fergie Reid’s 90th birthday on March 18, a massive voter registration drive is underway. The “90 for 90” project plans to register at least 90 voters in each of Virginia’s 2,550 precincts, to help commemorate Reid’s legacy.

A glance at the electoral map reveals what a game-changer this could be. If the “90 for 90” project can register the 250,000 new voters it intends to – or even achieve half of that – it could lock out Republicans from the Electoral College for good. It’s hard to see the GOP winning an electoral college majority without Virginia. And their situation is even more tenuous with the Clintons’ family friend and firm ally Terry McAuliffe in the Governor’s mansion.

“If Hillary wants to win Virginia,” Reid said, “Terry should get involved in the 2015 elections now.” The rationale is simple: Every dollar that is raised for Virginia’s 2015 off-year election, every voter who becomes registered, and every canvassing effort will fine-tune and strengthen a Democratic machine that will need to be in top form in an election where the Kochs and other GOP donors are expected to spend more than $1 billion.

The good news for Democrats is that they’re just one seat away from recapturing the state senate in Virginia. And there are two rising stars in their bench that Dr. Reid is particularly proud of.

Emily Francis is a long-time activist campaigning for the 10th Senate district in Virginia, which encompasses parts of Richmond, Chesterfield County, and all of Powhatan. She’s offered her full-throated support of Medicaid expansion, saying that it’s unconscionable not to give 400,000 Virginians the health care they need when a fiscally responsible course of action is already available.

“It shouldn’t be a partisan issue,” she told me. “I think it’s irresponsible not to help people in need.”

Francis has also been involved in voter registration drives since she was a college student, and shakes her head at the gridlock in the Capitol over voting rights. “Helping people participate is a fundamental part of our country. We should be aiming to make it easier rather than harder to vote.”

If she’s successful, she will win a traditionally red seat and perhaps hand control of the senate to Democrats. But she’ll have to prevail in an interesting primary first; her Democratic rival, Dan Gecker, is most famous for representing one of Bill Clinton’s accusers in a harassment case in the 1990s.

Meanwhile in the southeastern corner of the state, Democrat Gary McCollum is waging a courageous battle to unseat Republican Senator Frank Wagner. Virginia’s 7th Senate district, which includes part of Norfolk, is Democratic-leaning, with President Obama having won it by two percentage points in 2012. Incredibly, Wagner coasted in 2011 without a challenger. But he’ll have a fight on his hands this November, facing a well-organized and charismatic foe.

“He’s extremely qualified,” Reid says of McCollum. “He has a military and business background… the district is very winnable if he does the basic things like voter registration and getting out the vote.”

Electing one or both of these candidates could tip Virginia’s political balance in the short term, handing McAuliffe a major victory. It would be political capital he could spend in a major way, perhaps granting health care to 400,000 Virginians.

And in 2016, Ferguson Reid and the “90 for 90” movement can make history again by helping to elect another historic President — whoever she may be.

William Dahl is a recent graduate of The College of William and Mary, where he majored in Government and studied abroad in La Plata, Argentina. He has worked for community foundations in Argentina and Miami dedicated to community engagement and prosecution for human rights abuses. A native Virginian, he moved to Baltimore in 2013 to join a financial research firm, where he enjoys being able to write on the side.