Winter Classic before the NHL’s Winter Classic

I found out on Dec. 30 there really is no statute of limitation on having childhood dreams of hockey glory.

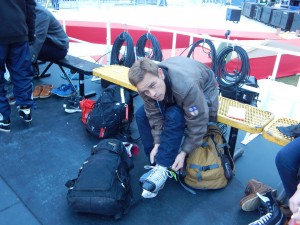

After what must be about a 20-year hiatus, I found myself lacing up a pair of skates and charging onto the ice again, but this time it was on the official rink of the Winter Classic, the National Hockey League’s annual New Year’s Day outdoor game being held this year at Nationals Park in Washington, D.C.

As a boy growing up in a small, suburban town in Massachusetts, the coming of winter meant one thing above all else: hockey.

The official start of winter was always marked by the first skate session on Frog Pond.

We’d see it begin to ice over and come back daily to break a test hole in the surface, trying to convince whichever neighborhood mom came with us that it was perfectly safe for us to skate. We’d apply all the principals of physics and thermodynamics that a 9-year-old’s brain could come up with in our arguments, usually to no avail.

My theory was that if I could stand on a one inch ice cube without crushing it, then skating on a frozen pond that thick was way more safe, since we’d have skates on and be moving faster than the ice could realize.

It simply wouldn’t have time to break. Genius, right?

Sir Isaac Newton couldn’t have put it more eloquently. And besides, the pond was only about 10 feet at its deepest spot anyway.

Moms are just too overprotective.

But the day would finally arrive – this was New England after all and bone-numbing freezes are the regional specialty. I’d hike down to the pond with my new Christmas stakes laced together and dangling around my new Christmas hockey stick, ready for battle.

Oh yeah, this was year I’d be discovered by an NHL scout who just happened to be roaming the woods of my little town. He’d hear the commotion down the trail and follow the noise, immediately recognizing that distinct sound of stick on puck as my ferocious slap shot echoed across the ice.

He sees a young man and thinks ”Prodigy! I must get this kid signed right now!”

I always liked to get to the pond early. If the hockey boys got there first, you could stake a claim to the good side of the pond, where there wasn’t as many swamp-grass tufts sticking up through the ice. We left shovels and an old push broom to clear any snow that fell overnight.

I’d become a one-man zamboni, pushing the snow into heaps at both ends of the rink, then sweeping the ice down to its bumpy, uneven beauty.

I’d stay all day, skating and playing hockey. We’d have games that would start as soon as two players showed up and would run until there was only one guy left. The players would come and go, the teams would shift to balance big kids and little ones, squads would range from two-on-two to five-on-five to as many as we could fit into the space. The score would build through the day, get confused and disputed and started again.

We had guys who took lessons and played in rink leagues, and guys like me who just had Frog Pond.

We ALL dreamed of playing in the NHL.

We all pretended to be our favorite pros. My hockey hero was Bobby Orr, probably because of an iconic photo of him flying Superman style after scoring a game-winning goal in the Stanley Cup. I’d try leaping to mimic that picture, seeing myself as the hero.

Someday.

I spent many years skating that pond and a few others like it until moving to warmer climates.

Those years are why I love the Winter Classic. It seems so odd to build a hockey rink in a baseball stadium, but to watch the game played outside, under the cold sun on New Year’s Day, truly does take me back to childhood.

And having the chance to skate the same ice as some of the game’s greats like the Washington Capitals’ Alex Ovechkin and Chicago Blackhawks’ Jonathan Toews was a bucket list item checked off for my 9-year-old self.

And most satisfying of all, after all those years, I didn’t fall once.

Maybe it’s still not too late.

Chris Swanson is a live music and sports fanatic and a long-time Maryland resident. He holds tightly to what some consider an unreasonable affection for the Baltimore Orioles and older music venues. Chris has a Communications Degree from the Franciscan University of Steubenville.